Leaving Delhi on a Friday morning, we cleared Kashmiri Gate by 7am. There was little respite from the sultry Gangetic weather until we passed through Mandi later that evening, when we were treated to a downpour. Forty kilometres further north, we stopped at a roadside town called Aut, from where we were supposed to phone our weekend host, “Mr Raju”. To get to Gushaini, Raju explained, we needed to turn off the main highway and take a confusing set of rights and lefts. “It’s best to keep asking people along the way,” he said. “And when you get to a parking area with some jeeps, honk. I’ll come out and help you across the bridge.”

Darkness had fallen by the time we pulled up to the banks of the Tirthan river and honked our horn as instructed. Within moments, a gaunt man was making his way towards us with a torch. “Hello, I’m Raju,” he called out, his toothy smile both awry and affable.

##151015164739-rgh3.jpg##

Following our host along a stony path that skirted the river’s edge, we finally gazed upon the notorious bridge. A one-inch-thick wire hung across the roaring Tirthan, and a metal basket hung from it on two pulleys. The metallic contraption wasn’t much bigger than a baby’s bassinet. “You people can cross the river on that thing,” our driver muttered, “I’m going to sleep in the car.” After a day of his erratic driving on hairpin curves, a vengeful side of me was gratified by his fear.

I cautiously stepped into the basket, and Raju pushed me out over the rapids. Midway across the bridge, Himalayan snowmelts surging beneath me, I inhaled the surrounding wilderness and smiled euphorically. This was going to be no ordinary weekend in the hills.

On the other side of the river, Raju showed us to the guest quarters and then brought us fresh apple juice. The three immaculate and warm guestrooms that occupy the first floor of Raju’s home are filled with custom-made wood furniture and multiple beds. Even the electricity outlets are adorned with pine. Hand-woven throws cover the beds and hand-made mobiles are draped from lights and ceilings. The bathrooms are modern but maintain a rustic feel with slate floors and wooden cabinets. Raju prides himself on his use of local raw materials.

##151015165048-rgh2.jpg##

Next came dinner, which was served in a cosy dining area. Phoebe, an endearing weasel-like dog, nuzzled up to my foot and begged for scraps. Raju’s wife Lata serves a different four-to six-course spread at every meal. On our first night, we ate Indian, the chef’s deft hands reinventing simple dishes like daal makhni, karhi chawal and rajma. In Lata’s kitchen, malai and ghee are delicacies that enhance flavour rather than disguise shoddy ingredients and culinary ineptitude. All sabzis are grown on the premises itself or nearby. While I usually steer clear of meat products, the locally raised mutton and chicken coupled with the sumptuous sauces forced me to abandon my pseudo-vegetarian ways. Lata normally serves up local trout, but recent floods washed away a nearby fish farm and depleted the river’s supply of wild trout. She also does Chinese and Continental, cleaner and simpler than any urban attempts.

Raju joined us as we devoured our dessert, custard filled with fruit grown on his 22-acre estate—grapes, apples, apricots, plums. While orchards provide him with the bulk of his income, running his guesthouse is more a hobby. “Actually, it’s more a homestay,” he says. “I do it because I enjoy it. It allows me to get acquainted with different people.” Rather than ending up loud and sprawling like Manali, Raju would like to see tourism in the surrounding valley develop using the homestay concept as a sustainable model.

##151015165140-rgh4.jpg##

Guests have been visiting his home in Gushaini since 1995, initially enticed by the angling. Besides the fish in the river, black bears, barking deer and monkeys are spotted on the property from time to time. When his dog Bhalu was just a puppy, Raju explained, while fawning over the sagacious red animal, he had a close encounter with a leopard that was prowling around the orchards. After telling stories around the table with our bellies full for another hour, we said goodnight. The valley’s symphony— river and crickets—coaxed me into the deepest slumber I’d had in weeks.

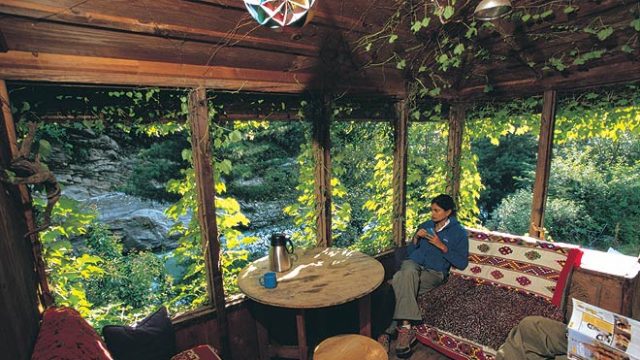

We started off our first morning sipping tea on the verandah outside our rooms. The verandah looks upon a perennial garden; in this season, orange gladioli and white dahlias were in full bloom amidst a savage arrangement of ferns and shrubs. Kittens and dogs lay languorously on the grass while butterflies feasted on the flowers. Behind the garden loomed the verdant summer hills of the lower Himalaya dotted with hundreds of ripe apple trees. For my second cup of tea, I went to Raju’s first-floor open-air conservatory that overlooks the river. Upstairs, ivy looped around window frames, Escher-like sculptures dangled from the ceiling and driftwood decorated shelves and cabinets. Enthralled by my surroundings, I didn’t even bother to pick up a book.

After breakfast and a jeep ride with Raju to the nearby Great Himalayan National Park, the strong afternoon sun seduced me into the Tirthan. A large boulder formed a pool a few dozen metres upstream, and I took off my sandals and shirt and waded into the freezing water. Although I only lasted a minute, drying on the rocks afterwards, I was relieved of the urban stresses that pervade my every movement, if only temporarily.

We didn’t take advantage of the ample walking trails until the next day. After breakfast, a zestful white dog named Yati—a cross between a Tibetan Mastiff and Irish sheepdog— led us on a hike up to a village called Bandal. The trail initially skirts the Tirthan and is largely free of Bisleri bottles and wrappers. But the destruction from the severe summer flooding is apparent below—a footbridge and the local school had been washed away. Beginning our ascent towards Bandal, villagers taking their livestock to graze greeted us warmly. Many were on a first-name basis with Yati.

Upon reaching lower Bandal, a girl named Surita offered to escort us to the upper village. With hazel eyes and sun-kissed skin, she patiently waited for us as we trudged up the mountain in the mid-afternoon heat, passing by sunflowers and morning glory. When we reached upper Bandal, a village with more than 25 homes, Surita introduced us to her brother, a muscular young man named Narmindra. He wore boot-cut jeans and had two crates of apples on his back when he shook my hand. His hair was cropped short except for his Brahminical lock, and he wore a tank top with a picture of a sensual woman and the legend “Beauty Queen, My Lover”. After asking us to remove our belts, he eagerly showed us the village’s mandir.

Outside again, taking in the still unobscured views of the valley, Narmindra told us that he had a BA in economics and was about to start an MA in English. “I’d like to sell life insurance,” he said. But a driveable road to Bandal will be opening up in the next couple of years, he explained. “Let’s see, maybe I’ll start a guesthouse or a hotel.”