Do you see the elephant?” asked my guide Sathish, pointing far into the distance. It was past 10pm. I’d been travelling the entire day. More importantly, it was pitch dark and I was on a road in the middle of nowhere. And, no, I couldn’t see anything, leave alone an elephant. But it was hard not to get taken in by Sathish’s infectious enthusiasm, so I looked harder.

About a kilometre away, behind boughs of trees, thick with lush green foliage, I finally saw an eye blink. That was my only glimpse of the wild Asian elephant during my stay at Anaikatti-By the Siruvani, a Sterling Holidays resort. But my trip didn’t lack adventure.

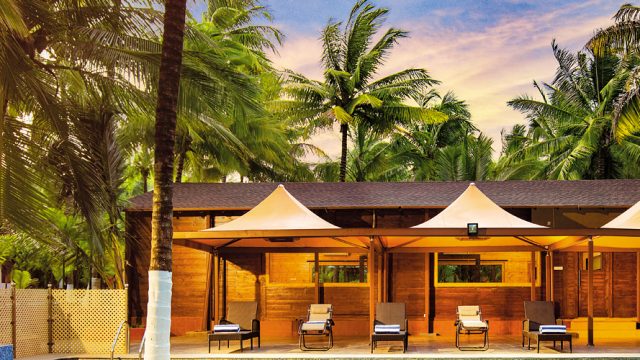

Built at the edge of the Silent Valley National Park on the border of Tamil Nadu and Kerala, the resort overlooks the river Siruvani, a tributary of the Kaveri. Its lush coconut and palm orchards are punctuated with discreetly spaced pinewood rooms and chalets. Winding, tree-shaded trails connect the rooms to the multi-speciality restaurant, pool, a well-equipped activity centre and a surprisingly fantastic spa.

The next day, I set out to explore the Silent Valley National Park with Sathish. Tucked away in the southwestern corner of the Nilgiri Hills, not far from Ooty, this small but densely forested plateau forms the core area of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. “The British named it Silent Valley because, unlike most forests, this one doesn’t have crickets so there is no sound in the forest,” he explained.

The result of unblemished natural beauty is the tendency of human beings to spoil it. Silent Valley is a beacon of hope for all who want to preserve nature and for rainforests around the world. It’s been at the centre of one of the fiercest environmental disputes in the country when a dam was proposed on the river Kuntipuzha to create a reservoir in Silent Valley. A unique and sustained environmental battle helped saved the only remaining undisturbed tropical evergreen rainforest in peninsular India.

Today visitors are permitted only up to Sairandhri, the spot of the proposed old dam site, 23km from Mukkali, a small town that houses the office of the Deputy Director of the Kerala Forest Department. Legend has it that this forest was once called Sairandhri Vanam. It is said to have been so dense that the Pandavas lived here anonymously through their year-long agyata vasa. Kuntipuzha is said to be named after Kunti, the Pandavas’ mother, and Sairandhri is another name for Draupadi.

It was a bone-rattling haul in a forest jeep through the buffer zone but that shouldn’t deter wildlife enthusiasts, for the rewards are endless. I spotted multiple giant Malabar squirrels, grasshoppers that looked like one of those paint-by-numbers projects with psychedelic colours and the region’s most famous residents—the endangered lion-tailed macaques. The protected forest is a safe haven for the Nilgiri langur and rare bird species like the Ceylon Frogmouth and the Great Indian Hornbill.

Once we reached Sairandhri, we were allowed only two kilometres inside the actual forested area. Our first stop was a 100-foot tall watchtower that overlooked the valley. Even though the watchtower is sturdy, I don’t recommend looking down while climbing up. Instant vertigo is guaranteed. “That’s Tamil Nadu in the distance,” Sathish pointed. All I saw was a jade mountain shimmering under the mid-morning sun. The panoramic aerial view of the ultramarine Kuntipuzha snaking through the bio-diverse jungle was simply breathtaking.

Next, we trekked down the mountain to a quaint suspension bridge across the Kuntipuzha. A relic from the contentious hydroelectric project, the bridge is a symbol of victory for the park. Skipping over tiny streams, chasing butterflies and dragonflies and being trigger-happy meant that I almost forgot to huff-and-puff on the climb up. Almost.

From the towering Culinea trees to the jewelled bugs on the forest floor, Silent Valley National Park is the ideal place to appreciate both outsized and minuscule wonders. High up in the canopy, a tribe of lion-tailed macaques were lolling about on thin branches as nonchalantly as Huckleberry Finn on a Mississippi log. On the sun-dappled forest floor, leeches lay waiting for their next host.

Sathish had pre-organised a special treat for lunch and after spending all morning at Silent Valley, we drove toward Koodapati, a tribal village. On the confluence of the Bhavani, Siruvani and Kodugara rivers, I sat down for an alfresco meal under a tamarind tree. Meenakshi and her sister had cooked a nutritious meal that included ragi, sambar and red rice.

Back at the resort, I made a beeline for the spa. An extended version of Balinese massage followed by a few hours of staring into space helped me unwind before the return to urban frenzy.

The Information

Getting There

Major airlines flying to Coimbatore International Airport are Air India, IndiGo, Jet Airways.

Where to Stay

Anaikatti-By the Siruvani, a Sterling Holidays resort, is situated about 55km from the airport, has 33 well-appointed guest rooms and chalets (from ₹5,500-6,500 for two per night, depending on the season, breakfast included, 04924-227100, bookings.sterlingholidays.com)

What to See & Do

Anaikatti means a ‘group of elephants’, which means you can see elephants in their natural habitat in the day and night. You can go for safaris, treks, enjoy the flora and fauna. The night safari can help you see nocturnal wildlife such as the Indian bison, otter, mongoose, leopards. One can see the tribal habitats of the Mudugas, Irulas and Kurumbas.