The northern regions of Kerala are known for their forbidding wilderness, warriors and revolutionaries. The name Wayanad means the land of paddy fields, but you can’t enter this district without feeling the drama of the forest. The slopes are steeper, the trees taller, the vines thicker and more tangled than we see elsewhere in Kerala. About fifteen years ago, the Wayanad region opened up for luxury tourism, and the fragile forest has so far seemed robust enough to withstand it.

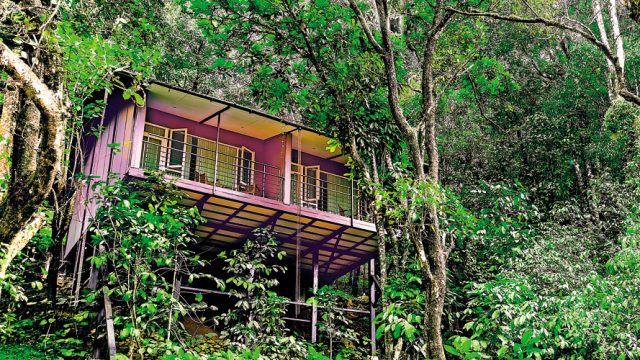

Wayanad Wild, a new resort that was soft-launched by CGH Earth this January, is built and run with the same sensitivity as the group’s other resorts, with clusters of rooms perched on a slope. When you walk out onto the balcony, you find yourself looking

at the higher branches of trees further down the slope. The air is cool here at an altitude of 2,900 feet above sea level, and even in March a light sweater is welcome in the mornings and evenings. Salvaged shipwood and bamboo accessories lend some warmth to the sleek steel structures; there is comfort here without ostentation.

At this stage, 22 rooms out of the planned 40 are ready. It’s that time of the year when the hilly landscape is scented with the blooms of coffee bushes and coloured with blushing datura. The resort covers just over 12 acres but it touches the buffer zone of a forest reserve, so the greens appear infinite.

In the evenings, once the birds have fluttered back to their nests, a campfire is lit and there is music in the air. On my first evening, the men and women who work at the resort sang a Malayalam song as we all sat by the fire, while a young Israeli guest plucked her ukulele.

Forest treks and bird-watching are the highlights of any stay in Wayanad. One of our walks brought us sights of the blue-tinted Malabar parakeet, the orange minivet, the flame-throated bulbul, leaf birds and a crested serpent eagle. Giant squirrels munched, plunged and lounged in the branches overhead. The panther-black forms of the elusive Malabar langur were a lucky sighting, but they fled when they saw us booted primates below. I also glimpsed the vanishing hindquarters of a sambhar. We peered at the curiosities of the forest—the wet mud nests of the rufous woodpecker, built by ants; the common jezebels and blue-bottles mud-puddling near a creek; the tiny leaves of the wild pepper vine; and the heaps of dried elephant dung on the path.

At the summit of each climb is where they keep their promise of the Wild. There is nothing but forest as far as the eye can see, with strokes of flaming pink from the tender leaves of the cinnamon tree.

On an evening walk, we met Chandran, guardian of the mobile tower in the hills. Our naturalist guide Varun asked if he had seen elephants lately. Yes, he said, two nights ago mooppar (the boss) ambled around this side of the hill so he, Chandran, decided to take the other path. On the previous night, an elephant tore a gigantic fantail palm in three pieces and still couldn’t get to the sweet inner stalk, he said. Chandran tells his stories with quiet amusement, smiling bashfully into the ground while we hang on to his every word. He ends with the tale of the furious elephant who tried to pin a man to the ground. But the fellow slipped between the tusks, behind the elephant’s trunk and out between its back legs like a mouse. Not all stories about wild elephants end happily though, as can be seen in the papers in Kerala. But that night, we chuckled over Chandran’s tusker tales as we lingered over dinner under the stars.

Meals at Wayanad Wild are understated but self-assured. Chef K. Velayudhan, who has worked with the group for over three decades, aims to serve local food. He goes to the Kozhikode market and makes the seasonal purchases himself. The fish he gets straight from the harbour. The meats of this region are mutton and chicken rather than pork. One popular item here is kingfish, stuffed with chillies and small onions. The rice most often served is Paalthondi, native to the district, and Gandakachaala, found nowhere else. Then there is the bamboo rice, gathered and cleaned painstakingly to be made into payasam, a speciality in these parts.

He modestly denies that he innovates, but there are dishes we tasted here that had been updated to more healthy versions: a wheat bran puttu, pazhampori encased in ragi, and millet upma and payasam. There were simple but mouth-watering desserts such as a slice of grilled pineapple with butterscotch sketched over it, and an adorable banana split made with the tiny nyaanipoovan banana.

Some guests explore further. A travel company called Muddy Boots offers individualised tours into the surrounding landscape that are not motorised or noisy. They run a zipline through a tea plantation, and from the endpoint you can meander back through the tea bushes or cycle around. It also organises forest treks and a one-hour glide through the crystal-clean waters of Anoothupuzha on a bamboo raft.

If even that is too much of a bother, just give up your morning walk for a morning watch from the balcony. One afternoon, butterflies saved me the trouble of a hike and floated one by one past me—the common rustic, a sailor, a blue-bottle and a Malabar tree nymph. I saw five bonnet macaques climb into the trees, cross from one high branch to another, and land on the roof of my room with five discrete thumps. As the light faded and the trees loomed, it seemed a good time to get together and tell ghost stories. In fact, I’ve got one for you from just down the road.

Back when Tipu Sultan ruled over these regions, the British looked for a way through the dense forest to mount their attack on him. They got Karinthandan, leader of a tribal clan, to show them a route. Once he did that, they shot and buried him. But their plan did not quite work out. The outraged ghost of Karinthandan created mayhem. Some say he was strengthened by the spirit of Mahadeva, lord of the hills. The secret road became impassable. It was then that an acharya used his sprite and a forest vine to bind the ghost to a tree. That vine became a chain and the tree is now known as the chain tree. Nearby lie the tomb of Karinthandan and stones to commemorate the acharya and his sprite.

The faithful say that the chain has never broken or rusted or grown into the tree. The links, they say, have no joint. A small lamp filled with oil in the morning stays lit till evening. When the road was widened and a bridge built, they say, the fury of Karinthandan brought disaster to those who planned and carried out the job. The chained ghost is still not entirely at peace. But that need not worry us. Who would want to get past this small slice of paradise?

The information

LOCATION Lakkidi, Wayanad District. It’s 61 km from the Calicut International Airport and a six-hour drive from Bengaluru.

ACCOMMODATION 22 standard rooms at present (no AC, no TV)

TARIFF From ₹10,000 to ₹15,000 per night (inclusive of all three meals and taxes); introductory rates available till September

CONTACT 0484-301-1711,

cghearth.com