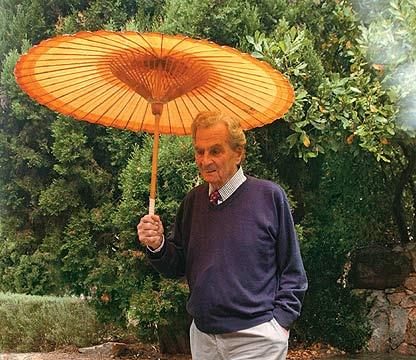

Patrick Leigh-Fermor, who died in June this year, managed to fit more into his quite singular life than most cities can hope to show. This is not an idle claim. It would be just about possible — if unlikely — to find people who have mastered several literatures, classical and modern, after having been thrown out of every school they attended, or walked across Europe, or have seduced (and been seduced by) everyone from grocer’s daughters to princesses, or been successful special forces soldiers whose crowning operation involved parachuting into Crete and kidnapping a German general, or been wonderfully entertaining singers and erudite storytellers over impressive quantities of alcohol.

Most cities will contain a few people who might have done a few comparable things. But the idea that there might actually be a single individual who had done all these things is almost laughable, but only such almost laughable comparisons help make sense of Patrick Leigh-Fermor’s astonishing life. And, in fact, his lasting legacy is unlikely to be any of these remarkable achievements. When he wasn’t making the lives of ordinary humans look as dull as communist concrete, he also found the time to write.

It is a relatively slim oeuvre; a couple of translations and collected letters and writings, a book on his time among Benedictine and Trappist monks, a novel and six travel books. Even the book that is possibly the least of these, 1991’s Three Letters from the Andes, about his travels in Peru, which was actually commissioned by his editor as a way to help him overcome writers’ block, contains some very good travel writing. So, too, are Mani (1958) and Roumeli (1966), which are both set in Greece, one of his great loves, and where he was to live for the last decades of his life.

But the first two books of the three he had planned to write about his walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople contains some of the best writing in the genre. 1977’s A Time of Gifts covers his journey from Holland to Hungary, while Between the Woods and the Water (1986) ends at the then Yugoslav-Romanian border.

That they were written several decades after the events that he describes lends a very unusual perspective. Somehow Leigh-Fermor manages to get the open-minded curiosity and sheer unalloyed joy of youth to segue wonderfully in and out of the learning and experience of a much older man. That learning can be dazzling, even intimidating. A relatively mundane passage involves an investigation into why Shakespeare (whatever his other gifts, no great geographer) might have thought land-locked Bohemia had a coast in The Winter’s Tale.

But rather in the way that, variously, mathematicians and classical composers might need to follow complex paths en route to a clear and simply stated resolution, Leigh-Fermor’s writing is ultimately making a simple point: how much pleasure there is to be had from other places, other cultures and, most of all, other people, for the open-minded and worldly.

There is, too, a tremendously elegiac quality to these books. They describe a Europe that cataclysmic war, politics and modern technology have since utterly transformed. One of the great Leigh-Fermor stories comes as an aside in A Time of Gifts. He jumps many years forward from his early travels to his World War II exploit of capturing the German general in charge of the island of Crete. As the kidnappers and their victim escape German patrols, they pause to watch a magnificent sunrise. The general quotes, as if to himself, a line from the great Roman lyric poet, Horace, and seamlessly, Leigh-Fermor recites the rest of the ode. As he later wrote, it was as though, “…for a moment the war had ended. We had both drunk at the same fountains long before, and things were different between us for the rest of our time together.”

It’s a lovely passage, a pitch-perfect summation of the most meaningful of all the experiences that journeys offer — the utterly transformative moment of first connection when you stop being a stranger in a strange land. Patrick Leigh-Fermor seemed to find those moments everywhere he turned. It is another famous line from Horace that says so much about the pleasures that await within his writings: Nunc est bibendum, nunc pede libero pulsanda tellus (Now is the time to drink, now the time to dance footloose upon the earth).