At Bharat Bhavan—Bhopal’s famous, Charles Correa-designed, red sandstone-clad multidisciplinary arts centre—the first person I meet is Yashwant Tekam, a young waiter at the canteen where I’ve stopped to drink a delicious mattha before taking on the exhibitions. Dressed in jeans and sneakers, and deploying his limited English with wonderful confidence, Yashwant tells me he’s actually an artist, with roots in the village of Karopani in the state’s Dindori zila. Waiting tables is his day job; at night he paints folk tales and stories about forest life with acrylic and watercolours on canvas and paper.

Meeting Yashwant, who belongs to the Gond tribe, is the best possible entry into an institution celebrated for having been the first to bring the art of central India’s tribal communities into the museum space. The painter Jagdish Swaminathan, after whom the road on which the Bhavan sits is named, was responsible, right from its start in 1982, for identifying and encouraging young tribal artists, and displaying their work alongside that of their urban peers. Today, this art is on exhibit at one of the Bhavan’s large galleries and part of its permanent collection of 6,000 tribal and folk art objects.

The work of some of those early pioneers—such as Jangarh, Pema Fatya, Bhajju Shyam and Durga Bai—has gone on to be much sought after by galleries here and abroad. And they have, in a manner of speaking, brought their villages with them. The gallery abounds with work by Tekams and Shyams—strikingly figurative art against plain backgrounds, often formed by an accretion of tiny coloured loops or dabs, depicting plant, animal as well as human life, the last never central but always part of a larger drama or pattern.

Across the courtyard from the tribal art gallery is the ‘urban’ art one but, unlike most museums, the Bhavan’s open-ended architecture means there is no singular and enforced way in which to move within this space. From tribal art one could stroll into the lounge next to the library (home to almost 20,000 books) where on display are screenprinted handwritten poems and drawings by some familiar names.

“Sitting down to eat, the sun and moon heap up my plate” reads the last line of Allen Ginsberg’s poem ‘Homage to Vajracarya’ while Vasko Popa writes of his wife’s wish to have “a little green tree / to run along the street behind me” and Arun Kolatkar’s Marathi verse is accompanied by an arresting sketch of a man’s profile cut out of a sheet of paper by a broken razor. These and other big names of the era—such as John Ashberry, Stephen Spender, Nicanor Parra, Tomas Tranströmer—were among the 26 participants from 21 countries brought together to share their work at the World Poetry Festival held at Bharat Bhavan in 1989, perhaps the only gathering of its kind ever organised in the country. The Bhavan has also been serious about Hindi literature, having fostered much discussion over the decades on the whole gamut of modern writers from that language.

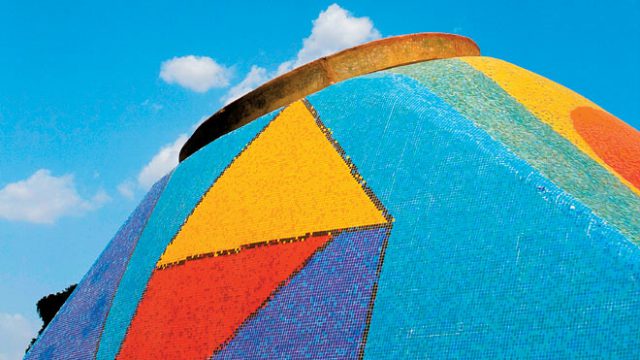

The Bhavan also has centres dedicated to film and theatre. A retrospective of Mrinal Sen’s film is on when I visit, and an exhibition of the works of a young artists’ collective from Delhi. The second art gallery impresses with glimpses of the work of some foundational modern Indian artists—Gulam Mohammed Sheikh’s typically storied paintings, S.H. Raza’s brilliantly coloured geometries, F.N. Souza’s brassy women.

I wander into the office of Prem Shankar Shukla, Chief Administrative Officer, for a chat and, finding it full of guests, excuse myself. But Mr Shukla insists I stay, informing me that all the gentlemen present are associated with the Bhavan and that soirée is the preferred mode of functioning here. I find myself talking to Dhrupad singer Ramakant Gundecha, one of the three famous Gundecha brothers, who runs the Dhrupad Sansthan in Bhopal and prior to that worked at the Bhavan. Also present is the artist H.S. Bhatty, now director of Roopantar, the fine arts section which includes the galleries and studios. Back in the day, Bhatty was one of the young art students Swaminathan handpicked and sent out into the villages to scout out tribal artists. The conversation soon turns to the origins of Bharat Bhavan.

In February 1982, a couple of hundred star artists took flights to Bhopal to be present at its inauguration by Indira Gandhi, apparently leading Charles Correa to observe that if those planes had crashed, contemporary Indian art would have practically been wiped out. In the first decade of its existence, such artists were associated with the institution in one capacity or another. I ask if the Bhavan retains its former glory. Of course not, say some of the artists present in the room. For the old visionaries such as Swaminathan and B.V. Karanth, the theatre doyen who set up the repertory at the Bhavan, are gone. Gundecha disagrees. ‘I hate nostalgia,’ he says and feels that the institution remains the only one of its kind, even though we’ve come a long way since the early 1980s and there are many more platforms for artists now.

Though Bharat Bhavan is funded by the Madhya Pradesh government, it is fairly autonomous and differs from a typical state-run institution in being able to cut out the red tape, says sculptor Devilal Patidar, joining the discussion. It’s possible here to secure approval to send a two-rupee terracotta sculpture from the village to the city at a cost of Rs 300, whereas a sarkari functionary would scuttle the idea. Shukla calls it an “anti-system” approach and says Correa’s design is itself “anti-building”.

Back at the busy canteen, Yashwant appears to be the only one holding fort, but he still breaks off to answer my questions. I ask if the inspiration for his art comes from childhood memories, or perhaps stories imbibed from grandparents? He waves away my romantic notions. ‘I am sorry, my grandparents died early. They couldn’t tell me any stories.’ It turns out that he has spent most of his youth in the city, first working in a railway coach factory in Indore and then here in Bhopal. I think of the art I have just seen in the two separate galleries, tribal and urban. Perhaps Bharat Bhavan, which once took the lead in trying to dissolve distinctions between artists, will some day come up with a third label to adequately describe Yashwant Tekam.