He carried his resignation letter in his pocket for a month, a bright young Bombay-based CA with a promising career in a big -ticket firm, and newly married too. He really didn’t want to give it all up for his family’s hotel business in ol’ Cochin. But persistent letters and trunk calls from his ailing father finally persuaded him to hand in the notice. Only for two years, the oldest of six sons told himself, till at least a couple of his brothers finished their studies, and off he would go. “That was in 1978,” recalls Jose Dominic, now the 65-year-old patriarch of the CGH Earth Group. “I got sucked in and never left. Tourism was only beginning to gain relevance back then. It was among the most heavily taxed sectors, in fact. It was very different from what we see today.”

His father, Dominic Joseph, opened the Casino Restaurant with two partners in 1957 (one of them had returned from Naples and wanted a name that evoked European decadence, and so it did). “Ten years on, they offered 32 rooms, and we later expanded to 70 rooms,” Dominic says. Things chugged along till Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi decided to go on what was to be a much-publicised holiday to the Bangaram island in Lakshadweep. That was in 1987. Soon after, Dominic was among the many hoteliers who received a cyclostyled (“We say Xerox these days”) invitation from the government to file an expression of interest for developing Bangaram, in return for which potential investors would be flown down to the island by helicopter. Bangaram was to be privatised. “The grapevine said all the big boys were going to be there,” Dominic says. “I applied just for the chance to see Bangaram—the journey by sea would have taken a month. It was only when I got there that I understood what a virgin territory it was.”

His formidable competitors compared Bangaram to Honolulu or Waikiki, they estimated that a hotel would need an investment of Rs 50-60 crore (money he didn’t have), and they wanted detailed studies before pitching proposals. Dominic thought otherwise. “I can tell you now,” he told the government authorities, “I can commission the hotel in three months. The more hotel, the less island. Instead, do what the villagers would do, live as they would.” Subsequently, an aghast Secretary of Tourism, who later became a friend and a votary of responsible tourism, wondered at the decision to award the contract to an unknown firm called Casino. The deal was signed in October 1988. Bangaram island began welcoming guests in December 1988.

Dominic spent in lakhs, not crores. He had the ‘fancy’ tiles laid for the PM’s visit removed, built minimally in the vernacular style, disallowed fishing in the lagoon (deep sea trips were arranged), water sports never went beyond wind and muscle power, every bottle opened on the island was brought back to the mainland for disposal, and if you smoked on Bangaram, you would bring the cigarette butts back in your pocket. There was no AC or TV or newspaper, no room service or hot water, nor swimming pool or multi-cuisine restaurant. Dominic pioneered concepts like carrying capacity, conservation of water and reduced noise levels, and installed only 24KW diesel gensets on the pristine island. “Such regulations were unknown at the time,” Dominic recalls. “We set our own safeguards. We saw them as our USP, not as restrictions.”

The dilemma, if it could be called that, was pricing. The Casino Group positioned its Bangaram island resort in the same bracket as the iconic Oberoi Towers in Bombay, to the shock of tour operators and peers alike. “It wasn’t for what we provided but for what you experienced,” Dominic says unequivocally. “The customer was not the king. The king was nature, the land, the community. On Bangaram, nature was undisturbed and undisturbable.”

It wasn’t easy being a pioneer. They went through periods of difficulty (after the Vayudoot and NEPC air services collapsed, Dominic had a five-seater from Panaji Aviation transport guests over multiple sorties, “just to keep the idea afloat”). Eventually, the famine in flights went on to become a flood of carriers and Bangaram island became a globally sought-after destination (the resort, however, is not functioning currently, following a ban on all private resorts in Lakshadweep, in a case that is now pending with the Supreme Court).

Bangaram opened their eyes, and Dominic says they brought this new learning to the mainland for the first time in 1991, with Spice Village in Thekkady. Here was frugal, ecologically conscious luxury paired with respect for the traditions of the local community—the instantly recognisable thatched-roof huts were adapted from the dwellings of the Mannan tribes; villagers clad in their native attire of mundu-jibba served local food like puttu-kadala and red rice instead of the mandatory Indian-Chinese-Continental mishmash seen all too frequently everywhere; and there was no TV in the rooms, which was a difficult decision for mainland India!

“All of this was very, very new at that time,” Dominic notes. “Spice Village ushered the first signs of responsible tourism into Kerala, and rumblings of growth in Kerala Tourism itself. Lakshadweep taught us that less is more—and it succeeded because of, and not in spite of, this philosophy. We are revalidating a return to our roots in nature and in local culture. The consumer finds value when his interests are superceded by that of land and nature. Over the years, this came to be called ecotourism and sustainable tourism, and now we call it responsible tourism.”

More never-before experiences followed. In 1992, Dominic collaborated with “Babu Varghese, a man of great innovation and ingenuity,” to launch the kettuvallam houseboat journeys—the Casino Group commissioned one from him, and Varghese owned the other. Today, there are 1,800 rice boats plying the fabled Kerala backwaters.

Coconut Lagoon, which came up in 1993, celebrated Kerala by rescuing and transplanting old homes that were being ripped apart for their timber. It was mostly foreigners who arrived in droves, but when travel to and from India came to a standstill after the Surat plague scare of 1994, Indians learnt to explore and discover the subcontinent like never before, heralding a whole new era of tourism in the country. The Kerala backwaters experience offered by Coconut Lagoon became so famous that tour operators in Gujarat put up ads urging tourists to go to Kerala and stay at Coconut Lagoon (one rumour went that Gujarati girls could not get married unless a honeymoon at CL was promised as part of the dowry!).

Dominic drew inspiration from local ethos everywhere he went. The Marari Beach Resort was modelled along the lines of a fishing community, given its location in the village of Mararikulam, with 16 coconut-thatched cottages (though they are air-conditioned here) following the principles of renewable energy and zero waste in a way that, “the hotel was not distinguishable from the village.” The brief given in 1998 to the architect of Brunton Boatyard required that the hotel be built with the same material (chiefly terracotta, lime and wood) that would have gone into the making of the century-old boatyard, which originally existed on the property.

By 2004, the Casino Group had played a significant role in creating the legend of Kerala as a destination, and the group was rebranded with the proprietary prefix of CGH Earth, which stood both for the widely respected Casino Group of Hotels and for ‘Clean Green and Healthy’.

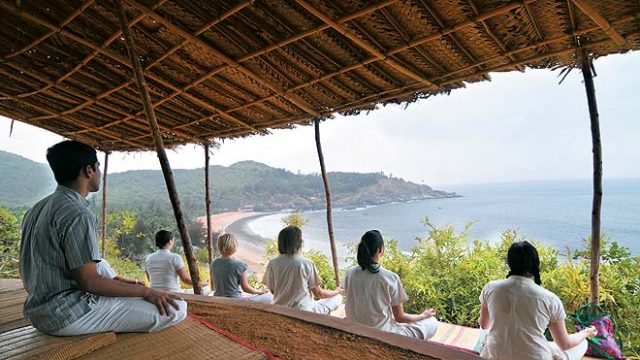

Sustainable practices are followed across the group’s resorts, and local innovations in responsible tourism abound—the yogo-centred SwaSwara in Karnataka relies entirely on harvested rainwater, without drawing on the ground water table (an organic farm supplies the farm-to-fork restaurant here); solar panels power the 65KW plant that meets 80 percent of the energy requirements at the 50-room Spice Village; 60,000sqft of roof made from coconut thatch is renewed every 15 months at the Marari Beach Resort, keeping an old tradition alive and providing livelihood opportunities for local craftspeople; only vessels made of bronze, copper, stone and clay are used for cooking at Kalari Kovilakom; the grounds of Coconut Lagoon are home to the dwarf Vechoor cow, part of a breeding project for a dwindling species; Christmas decorations at the Casino Hotel use only recycled material.

“We offer experiential holidays with responsible tourism at the heart of our core values,” Dominic says with justifiable conviction. “In Kerala’s growth, there is India’s growth. India is not for those seeking the familiar, but for those who search for difference. No other country is so well-endowed with such diversity.”

CGH Earth’s properties are centred around the Alert Independent Traveller, a term coined by Peter Aderhold, the noted Dutch academician, who embarked on a large sample survey of 5,000 people in 1986, dividing the tourism economy into two classes of travellers—the ‘sun, sand and surf’ tourist who only wants the familiar, whether in brands, food, company or experiences, and the democratic and humane AIT, who eschews the familiar and seeks difference in voyages of wonder and discovery. “We can’t cater to everyone,” Dominic says. “We seek the emerging modern customer who has a sense of the place and comes with respect for it.” Aderhold’s study found that the majority of the surveyed population preferred ‘sun, sand and surf’, with only about 10 percent inclined to be AIT. It’s this minority that has always interested Dominic, who adds, “They will choose us because we believe in this. Those who don’t find this delightful, it is better they walk away. ”

And yet the footfalls keep increasing. In 2004, the queen of the Vengunad palace in Kollengode called to ask if the ancestral home could be developed into a hotel. Yes, certainly, she was told. But she had an unusual concern. Meat and wine had never been served in the palace, nor had anyone ever worn leather footwear within (even the erstwhile viceroy Lord Willingdon had removed his shoes before entering the palace when he visited in 1928). Thus was born Kalari Kovilakom, the old-style ‘palace for Ayurveda’ embodying the principles of austerity and abstinence over 2-3-4 week programmes offering authentic Panchakarma therapies. Again, the ‘strictures’ were greeted with skepticism and occupancy stood at 5-6 percent in the first year. “I was asked to make it a one-week package, and to add a glass of wine and may be a piece of fish,” Dominic reminisces. “I wondered if I had bitten off more than I could chew but I held on and today, it’s our most successful product.”

Since then, he has expanded further within and beyond Kerala, his signature on a variegated range of extraordinary experiences (there’s also the single-key Chittoor Kottaram and the colonially styled Eighth Bastion and Beachgate Bungalows in and around Kochi and the wellness retreat of Kalari Rasayana in Venad; the Chettiar mansion called Visalam in Tamil Nadu; and the Franco-Tamil Palais de Mahe and Maison Perumal in Pondicherry). He is also experimenting with the concept of Vanavasa near SwaSwara, three cottages offering a ‘rewilding’ of one’s own self in total seclusion, minus the trappings of a routine, or even electricity!

With 15 boutique properties that have a clutch of national and international green excellence awards between them, the CGH Earth Group now employs 1,200 people and offers 370 rooms. With his heirs poised to take the group’s presence beyond the peninsula, Dominic still leads from the front, serves on innumerable advisory bodies and panels for responsible tourism, and is a founder-member of the Ecotourism Society of India. “Tourism is not about how many dollars we earn or how many heads we count, even though, unfortunately, that’s how it is often seen,” he says. “If that’s all it is, tourism would be a juggernaut that destroys everything in its path, like what has happened with many of our hill stations. In fact, tourism is about how much we can conserve of our ecology, heritage, culture and community. I believe responsible tourism is the only option that will work.”