On a driving holiday many years ago, our aged Fiat broke down in the middle of a remote village in Madhya Pradesh. I stepped into a round thatched hut with cool mud-washed interiors, where a woman served me water in a tall copper glass. Then she shyly asked if we would eat in her home but by then we had managed to get the car going. A little later, though, we were starving and stopped at a village eatery. The man literally opened shop for us — pumped the stove, cut vegetables and kneaded dough. The rough dal-roti that late afternoon tasted divine. I have always wanted to do more of this — drive into remote villages and stay awhile.

The truth, though, is that the Indian village experience is not really that easily accessible. It’s not just a question of getting there — once there, where would you stay and how would you handle the happy disregard of basic sanitation needs? Thus, the anticipation that greets the government’s completion of the Rural Tourism Project that was launched in partnership with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The idea is not only to package rural communities in such a way that local ways of living, art, music, dance and culture are sustained but also to encourage infrastructure development. Says an official of the Ministry of Tourism: “Our aim is to develop tourism in rural areas in a sustainable manner.”

Admittedly, though, the concept is not exactly new. Private operators caught on to it years ago, and have done some excellent work. Way back in 1991, an organisation called Help Tourism launched a demo project in West Sikkim for a village-based tourism initiative. All 40 families in the village are involved, offering home-stays or restaurants that mostly target special-interest travellers like trekkers or climbers. The facilities are clean and comfortable, not five-star since the focus is on the rural experience, and the costs match up. Today, the project has been replicated in 22 places across Northeast India. Says Asit Biswas of Help Tourism: “We try to provide meaningful local experiences through walks, village visits, etc.”

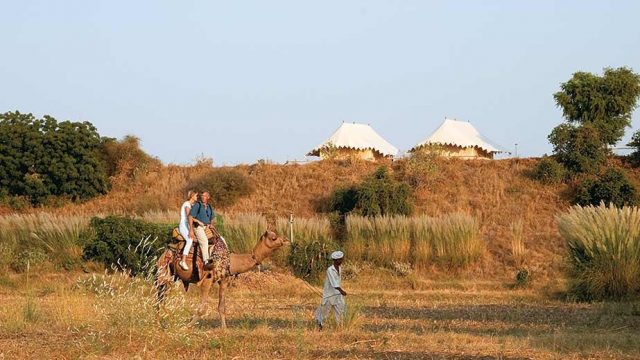

Similarly, in the Chettinad region of Tamil Nadu, the efforts begun about a decade ago by a couple of local families to resurrect their rich heritage and display it to the outside world has resulted in Chettinad slowly becoming a tourism destination. Rural tourism of another cut has also been available in states like Rajasthan that have heavy inbound traffic. This is the experience built around a luxury hotel like Castle Mandawa. Before Randhir Singh Mandawa started his home-stay in 1980, even vegetables weren’t available in this remote village in Rajasthan’s Shekhawati region which today boasts of refrigerator showrooms. There are other places as well, like Harsh Vardhan’s Chhatra Sagar at Nimaj, a camping resort that was once a royal hunting lodge, or Shahpura Bagh, the royal residence of the Rathore family, both in Rajasthan.

The leitmotif of these experiences, though, is the luxury stay. Says travel consultant Shoba Mohan: “Rural tourism of this kind is a little elitist. The opulent stays are the selling point and the village is ‘also’ done.” The Mandawas or the Rathores are all part of erstwhile noble families who have converted their palaces or lodges into high-end resorts. Tourists, especially foreigners, throng to these places because they get the ‘maharaja treatment’ while at the same time real India is just across the road.

This luxurious access to India’s villages comes at a price: anything between Rs 6,000 and Rs 24,000 per head per night. Hardly what the average tourist can pay, which makes the Rural Tourism project crucial if we are to open up the country’s interiors. The masterstroke has possibly been UNDP’s involvement in the pilot project that involves 36 villages. This means that basic issues like credibility and local involvement are being given due importance.

Overall, rural tourism needs to be handled with sensitivity and plenty of plain sense, a challenge that UNDP is aware of and trying to tackle. Says Prema Gera, UNDP, who heads the project: “Plans must emerge from the community and be run by them if this is to work.” UNDP is working everywhere through local NGOs, training them in the dynamics of tourism through workshops and interactions with tourist operators.

For starters, 37 sites have been identified for the pilot project, all of them already on the tourism circuit with some kind of attraction like a fort or pilgrimage spot. UNDP contributes Rs 20 lakh per site towards software, which includes awareness creation or liaising between locals and outside agencies. The government contributes Rs 50 lakh per site towards hardware, which is basically construction, sanitation, marketing, etc. Interestingly, some of the most important work has been the restoration of ancient wells and tanks, ports and temples, and local crafts. In places like Hodka in Gujarat or Samode in Rajasthan, the effort is quite impressive. For instance, tourism in Samode used to be about the luxury stay at the Samode Palace. Now, you can stay at village huts that have built a first-floor room with attached bath, and villagers have been trained in hospitality and guide skills. According to Gera, tourists can even choose to stay with village artisans and learn a craft.

The project has tied up with hotels or hotel management institutes to train villagers in cuisine, cleanliness and sanitation. Also, importantly, institutions like IRMA (Institute of Rural Management, Anand) and heritage architects have been roped in as consultants. Says Gera: “We want to retain vernacular architecture, perhaps with a little landscaping that’s in tune with the surroundings.”

This ability to tune in to the nuances of local culture and heritage has thus far been the strength of the royal stays, helping them score brownie points despite costing the earth. These families not only own large tracts of the surrounding land but are emotionally connected to the people. The Shahpura family, for instance, got the land from Shah Jahan in the 16th century. Says Jai Singh Rathore, a family scion: “A percentage of profits is ploughed back into the village.” The families protect the integrity of their fiefs fiercely. Their mansions do not accommodate more than a dozen guests at a time. Guests are not encouraged to give away pens and junk to village children, or donate money except to educational or other projects. In turn, village huts have not overnight sprouted glass-fronted façades, often because of direct intervention. Says Chhatra Sagar’s Harsh Vardhan: “It’s cheaper for a villager to replace his slate roof tiles with concrete unless we pay for the old-fashioned roof.” The idea is to encourage villagers to stay tuned to their old ways by making it financially viable.

An inability to be as culturally sensitive is perhaps the bane of the government project, as Gera admits. In a Haryana village, for instance, the local administration has insisted on building an air-conditioned tourist home. Everywhere, its tendency to go wild with cement and clichés is tough to curb. In a Bengal village, it has gone ahead with a Dilli Haat look-alike while in the middle of the Shekhawati sand dunes is a hexagonal cement kiosk that nobody quite knows the use of.

However, the government’s involvement is vital in areas like sanitation, roads, drinking water, signage and street lighting. Says Mandawa: “In a year 25,000 tourists come to Mandawa alone but the Delhi-Mandawa road is a mess.” Worse, severe water seepage threatens the lovely frescoes on village walls but nothing has been done about drainage.

According to an official, the Tourism Ministry’s involvement is to give basic inputs, such as making the village recognised. The rest of the project involves the convergence of all other rural-level schemes and the involvement of agencies like the Public Works Department or the Irrigation Department, with the district magistrate or collector acting as the focal point. This, unfortunately, does not seem to be happening as efficiently as it should. Says Gera: “It is vital to sensitise bureaucracy. Often, all that has to happen is for a collector to change and the whole project goes back to square one.”

This is UNDP’s last year with the project, and the Ministry of Tourism has meanwhile extended the work to a total of 125 villages. Although it means to go on the way it started, there is still a lot that needs to be addressed. Clearly, the government’s task is to provide the financial and infrastructural support that will allow local communities to develop the village. Gera says: “The government, NGOs and the community must work together, but the community has to be strongest.” While it will be a while before the success of the project can be gauged, some good work has been initiated and will hopefully be continued in the right direction.

The winner

The National Tourism Award for Rural Tourism for 2006-07 has gone to Chettinad. That’s excellent news. But why exactly did Chettinad get the award? The trouble is, nobody knows. Least of all, the Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation, the recipient of the award.

What we did manage to get from Dr M. Rajaram, Commissioner of Tourism, were the budgetary allocations for various projects initiated under the Rural Tourism scheme. About Rs 7.9 crore has been sanctioned so far, funds earmarked for vital areas like improving roads, organising solar street lighting and desilting the oorani or village tanks. Work in all these areas has started. Says Dr S. Bakthavatchalam, Deputy Director, “The work should take another year to complete.” Meanwhile, the best things in this region famous for its fabulous family mansions are still its own and fostered largely by private efforts.

While the government’s focus on marketing and infrastructure is welcome, the problem arises when it wants to do more. Thus, we have clumsy ideas like arches at the entrance of villages or boating in century-old village tanks. More alarming is the decision to build a massive bus-station in the heart of Karaikudi (the region’s main town) in order to place it on the Chennai-Madurai-Trichy temple circuit.

While this will increase arrivals, it is obvious that Chettinad does not have the wherewithal to handle these numbers. The problem with such areas is to find a delicate balance between increasing tourism while still preserving the heritage and charm that attracts tourists in the first place. Government plans talk of bed-and-breakfast homes, bullock-cart tours and village lunches but it’s not clear if these have been thought through. According to Meenakshi Meyyappan, who owns heritage resort The Bangala — the first such initiative in the region — getting the conservative Chettiar families to open up their splendid homes for tourists to visit is itself an uphill task. TTDC’s Bakthavatchalam agrees, “It is difficult; we are trying to identify single-owner homes to convince them to start heritage hotels.”

The area right now has three such resorts — the Meyyappan family’s Bangala (www.thebangala.com), the SARM family’s grand Chettinadu Mansion (www.chettinadumansion.com), and the CGH Earth group’s Visalam (www.cghearth.com) all catering to high-end tourists. The average visitor has no attractive place to stay if he wants to soak in the riches of Chettinad. This is a gap that rural tourism can indeed fill but should do without degenerating into mass tourism. As Visalakshi Ramaswamy, who has a charming museum in her family home, points out, “Chettinad cannot handle bus-loads of tourists.”

The region’s attractions are obvious — fabulous mansions, charming villages, and superb local crafts like basketry, cotton weaves or the famous Athangudi tiles. The challenge is to open it up to more people but to do so with restraint.

Model villages

Of the 37 sites identified by the Rural Tourism project, 15 are in an advanced stage of development, according to UNDP’s Prema Gera: Jyotisar (Haryana), Naggar (Himachal Pradesh), Samode (Rajasthan), Hodka (Gujarat), Pranpur (Uttar Pradesh), Chaugan (Madhya Pradesh), Banawasi (Karnataka), Kumbalanghi (Kerala), Aranmula (Kerala), Sualkuchi (Assam), Lachen (Sikkim), Ballavpur Danga (West Bengal), Nepura (Bihar), Pochampalli (Andhra Pradesh) and Karaikudi (Tamil Nadu).