In the 15th century you would have been lucky to live 35 years. In that era, Sultan Mahmud Begarha of Gujarat ruled for 53 years. In one account we find him, “A mountain of a man with a long moustache (that he tied above his head!) and stately person, having an inordinate appetite.” Another, more vivid description, has him swallowing “a cup of honey, a cup of butter, and 100-150 bananas” at breakfast, and another 10kg of food during the course of the day. And oh, the Sultan made it a point to sleep with “two pounds of rice” on either side of his bed, so he would have something to eat on whichever side he awoke.

This Sultan is buried in Sarkhej, a suburb of Ahmedabad. It is hardly 10km from Ahmedabad railway station, where I am waiting on a cool February morning. I do not have a hotel reservation in the city, and my train to Delhi does not leave until 4pm. So I suppose I have enough time to call upon His Highness in Sarkhej.

Begarha was more than a glutton. He is considered the most powerful of the Gujarat sultans. His title Begarha refers to his conquest of two (be) important forts (garh): Girnar and Champaner. Yet he lies forgotten, like most other monarchs who have ruled down the ages. Sarkhej today is almost entirely remembered for the Muslim ascetic Sheikh Ahmad Khattu — popularly known as Ganj Bakhsh (bestower of wealth) — whose seat it was.

Sheikh Khattu was an extraordinary man for his time, for he lived to see 111 summers. When he was born in 1336 AD, Gujarat was a mere province of the Delhi Sultanate. Muhammad bin Tughlaq, the eccentric sultan of Delhi, was raising a force of 370,000 troops to conquer Transoxiana, Khurasan and Iraq (the project was finally abandoned). And when Khattu died in 1445 AD, the Tughlaq dynasty had run its course, Timur’s sack of Delhi was history, and even the Sayyid throne in Delhi was about to be toppled by the Lodis. Also, Gujarat had been an independent kingdom for half a century.

Sheikh Khattu was eagerly courted by the Muslim nobility of Gujarat. His austerity and piety had earned him the highest regard, and Sultan Ahmed Shah, Begarha’s grandfather, proved to be his most ardent disciple. But the ascetic refused to live in the sultan’s newly-founded capital, Ahmedabad, although it had been set up on his advice. Instead, he stuck to his nest in the weavers’ settlement at Sarkhej, about five miles out of the city.

Sheikh Khattu eventually outlived even Ahmed Shah! On his death, he was accorded a simple burial befitting a Sufi, but a year later, the new sultan, Muhammad Shah, started building a mausoleum over his grave that would be the largest of its kind in Gujarat. This square tomb, which took six years to complete, measures 32 metres on each side. Yes, the Mughal tombs of Humayun, Akbar and Shahjehan are much larger, but they were also built much later, for emperors, under a stronger power. In the mid-15th century, the tomb of Sheikh Khattu was probably the largest on the Indian subcontinent. It was definitely bigger than any mausoleum raised by a Delhi sultan for himself.

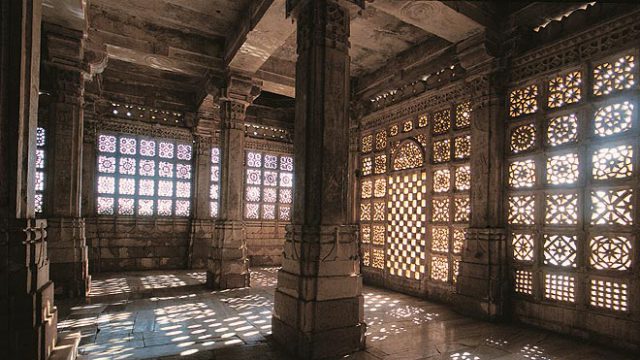

When George William Forrest, author of Cities of India (1905), visited Sarkhej, he was treated to a fantastical account of the tomb’s construction: “Before he [Sheikh Khattu] passed from this world to the Paradise of our hopes, he built this rauza. The labourers and artificers employed by him were daily paid their hire, and the good genii who supplied the funds deposited the exact quota to be appropriated beneath the carpet of the holy Ganj Baksh.” The belief is still current among many of the poor devotees who show up every day to pay obeisance. But while Forrest did not believe a word of it, he did admit: “It is certainly a delightful mausoleum.” He was especially struck by the stone screens “wrought with lavish luxuriance of imagination and incredible perfection of detail”.

The mosque alongside the tomb impressed Forrest no less. And he agreed wholeheartedly with archaeologist James Fergusson’s observation that, “Except the Motee Musjid at Agra, no mosque in India is more remarkable for simple elegance than this.” The mosque at Sarkhej is quite large. Its sanctuary measures 45.72 x 20.12 metres, and is topped by many domes held in place by 120 pillars. And, like the tomb of Sheikh Khattu, it is in excellent shape.

Amongst Muslims, the tomb of a saintly figure often becomes the nucleus of a necropolis. So it happened in Sarkhej that members of the royal family chose to be buried close by the holy man. Mahmud Begarha first converted the Sarkhej complex into a royal retreat with a large tank and pleasure palaces, and then added his own tomb across the courtyard from Sheikh Khattu’s rauza.

While Begarha’s palaces have fallen into disrepair, his tomb is in good shape. It is lit entirely by the sun’s rays creeping in through the intricate screens carved in the thick stone walls. Under the high, heavy dome, the air is always cool. Ruthless though he was, Begarha is every bit a saint in Sarkhej, and you must enter his ‘court’ barefoot. It takes a few moments for the eyes to adjust to the darkness, but then there’s no mistaking the sultan’s sarcophagus among the several that rise from the floor. The man-mountain indeed lies under a mountain of marble. Nearby, under another dome, rest some of his queens, including Bibi Rajbai, mother of the heir apparent Muzaffar Shah II.

When Forrest had finished sightseeing, he and his companions dined amidst the ruins. “The night was cool, and fragrant with orange blossoms… The moonlight slept on crumbled wall and marble pillars,” he wrote. You might not stay that late, but Sarkhej will still leave a lasting impression upon you.