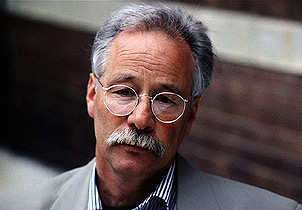

Had W. G. Sebald (1944-2001) lived longer, he would almost certainly have won a Nobel Prize for literature. Probably the finest writer of our times, this elusive figure produced four masterful books in the span of less than a decade, and then died. The disconsolate reader can tell herself that perhaps this cessation of his life and work makes a kind of sense, because already by the time of his last book, it was neither necessary nor possible to improve upon the perfection of his writing.

Sebald, a German who wrote in German even as he lived and taught in England, was preoccupied with Europe—with its literature, its wars, its cities, and above all, its history. He perceived the past not as a time dead and gone, but as a residue that covers the present, a snow that has settled over Europe’s buildings, its landscapes, and the consciousness of its people. For Sebald, the great suffering unleashed upon humankind by the colonizing nations, and upon Europe itself by the Nazi enterprise, has yet to disappear. Europeans live in the aftermath, among the ruins of this accumulation of suffering. By Sebald’s own account, the impress of even the most cataclysmic historical events eventually fades, but the effects of colonialism and the two world wars are still discernible to him, still constitutive of European reality as he experiences it. It is a startling thing for a reader in the post-colony, to have this glimpse into the heart of empire and find it as ravaged by its quest for power as it left many parts of the world, not least our own.

There is no way to summarize Sebald’s beautiful artefacts. They have to be read, individually and as a body. None of them, save perhaps Vertigo (German 1990, English 1999), seems to have lost anything whatsoever of its sublime quality in the translation. The Emigrants (German 1992, English 1996) is about the German-speaking Jewish Diaspora in the twentieth century, as captured through the life histories of four individuals. The Rings of Saturn (German 1995, English 1998) is the record of a walking tour through the small towns and villages along the coast of East Anglia. Finally Austerlitz (German and English 2001) is about a Holocaust survivor—the story of a child whose lost childhood is the end of Europe’s innocence.

Can these be described as works of fiction, of biography, of travel writing, of reportage, or of history? The question of genre is a very difficult one to settle for Sebald. All his books are punctuated with photographs. These are never particularly striking for their composition, content or quality of reproduction, and yet they are always present as silent witnesses, as documentary evidence for what might be called the ‘truth’ of the narratives they accompany. Very often the narrative itself is an account from an interview, a letter, or a journal entry, but it reaches us neither through straight quotation nor through elliptical paraphrase. There is no access for us to the worlds and words of these people – they cannot properly be called ‘characters’—except through the author’s re-imagining, re-living and re-telling of them. The tapestry of authorial and reported voices is seamless. The text is a replica of memory, but present in the text is memory belonging to more than one mind. The detail is so acute that language itself becomes photographic.

In writing of the ravages of war, of the decimation wrought by both weapons and ideologies, it is easy, perhaps, to take sides, to be didactic, to pronounce a verdict. It is far more difficult to get at the ubiquity of evil, the persistence of suffering, the futility of temporal power, no matter who the winners and losers of a given history.