Would you like a tiger by your bedroom window? Think carefully. It’s a serious offer, but with no guarantees. There rarely are, in life—or in wildlife sightings. That said, there is a fair chance that the Royal Bengal Tiger—or a leopard, or sloth bear, or sambar deer—will stroll past your window when you are in deep slumber.

Next morning, instead of your morning newspaper with your cuppa, you could ‘read’ the jungle telegraph—pugmarks on the sand, scat in the bush, maybe a quill dropped by a porcupine, a flurry of feathers, a broken bone—to show that a predator had had a good meal. Or you could check the strategically placed camera traps, to see which animal has taken its selfie (the cameras are triggered automatically by motion detectors when wild animals pass by) by the waterhole some 30 yards from the bungalow at tigress@ghosri, a pretty perfect wildlife lodge outside Tadoba.

This is a spectacular conservancy. I hesitate to use the word ‘resort’, because that would be to simply club it with several other establishments that may qualify in terms of beauty and service and surrounds but lack that vital element—a heart.

I am a tough one to please as far as wildlife tourism is concerned. The fallout of irresponsible tourism is troubling: trash, noise, crowding, harassed wildlife. What worries me even more is the proliferation of resorts that tend to wall in a reserve, thus blocking off crucial wildlife corridors. A classic example is the Corbett tiger reserve where a wall of resorts has practically cut off elephant and tiger movement to their source of water, the Ramganga River.

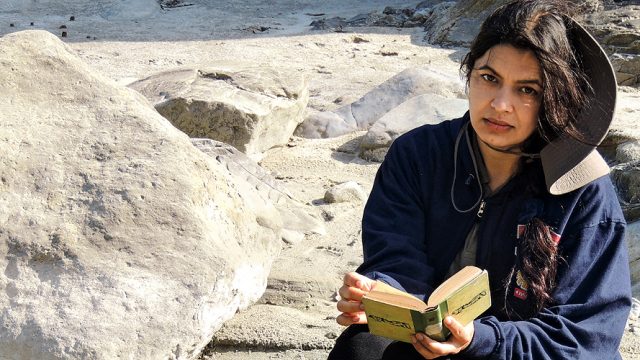

Tigress@ghosri is a different story, and it left me greatly impressed. Much before the place was thrown open to travellers, owners Poonam and Harsh Dhanwatey first set about protecting this area and securing it for wildlife.

Poonam and Harsh are veterans of the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve, now a high-profile park. When the couple started visiting it over two decades ago, the park wasn’t on the tourism circuit. They toured every inch, pitched in during the census, helped douse forest fires and helped calm frayed nerves on the rare occasion when tigers killed cattle, or men. It was their love for the forest that led them to scout for their own sanctuary—and this seven-acre plot of land in 2000, in the village Ghosri. It was a barren tract of land, with three mutilated neem trees. The surrounding forest was equally degraded—overgrazed by cattle, trees hacked for firewood. The private plot sat on a chicken neck that connected two parts of the reserves, and was hence a vulnerable patch for passing animals.

That was the clincher—the Dhanwateys bought the land and set about securing it for wildlife.. They first stopped the grazing and started planting grasses and trees. In this, they were helped by birds, bees, bats and butterflies—pollinators, all—and soon the land was lush with indigenous grasses, shrubs and trees, including palash, babul and tendu. Poonam laughs as she points out the tendu trees (the leaves are used to wrap bidis). They owe these to the sloth bear, from whose droppings sprung the tendu saplings.

One of the first things they did was make a waterhole—and this was not unlike sending an engraved invite to the denizens of the forest, who started dropping by for a drink. One of the first and regular visitors was a tigress with her three young cubs. It is in her honour that the waterhole was named ‘tiger taka’, and the lodge tigress@ghosri. Her cubs, now adults, continue to drink at tiger taka.

Not everyone was happy with the wild visitors, though. Some of the labour packed and left when a sloth bear strolled by, a few used a leopard sighting to demand higher wages due to the ‘risk’ attached to the work! The Dhanwateys responded by using the wildlife knowledge of the local people, roping in the village youth, who went on to become part of their team—as naturalists, guides or members of their wildlife-monitoring/conflict-mitigation teams.

And so, over the years, the forest home was built and expanded (though it takes up less than three per cent of the land; the rest is wilderness), and is today an extremely comfortable, even luxurious, retreat on the edge of the Tadoba tiger reserve. The food is simple, locally sourced and delicious. You could go for safari drives: Tadoba is an incredibly beautiful park which promises easy sightings of an array of wildlife (I met a sloth bear with two cubs, piggybacking). Or go birding at the Irai reservoir, or walk the buffer, and up Ghosri hill for a bird’s-eye view. Or hunker down on their spacious verandah—and watch from a safe perch as wild animals come calling: a pair of jackals, a family of mongoose, a lone sambar and, most beautiful of all, a kaleidoscope of butterflies. Hundreds of them, in myriad hues: blue tigers, common tigers, pansies, monarchs. Harsh said this influx happens every October. I tiptoed around the forest, naturalist in tow, walking amid clouds of butterflies as they looped and whirled around us. A few brushed past my face, some settled on my arms, tickling, as they sucked in the salts of my sweat.

I missed my tiger by a whisker, though. As soon as I entered the property I saw the huge pugmarks belonging to a feline named Gabbar. He had passed by early that morning, but chose not to come again the three nights I was there. But naturally, no sooner had I reached Nagpur airport that my phone beeped. “Come back, Gabbar is here,” read the SMS.

I cursed. Yet, could only feel a sense of pure pleasure, and peace, to know that tigers and their ilk had found a safe haven here.

Tigress@ghosri is located 2hr/135km from Nagpur, at the edge of the Tadoba-Andhari National Park (from Rs 9,990 doubles, all inclusive; 9011930649, tigressghosri.com).