The Aam Aadmi Party has been felled by a narrative of its own creation. The party has selected three candidates to be members of the Rajya Sabha but two of them are Guptas, or from the trading community (Baniya) in the Hindu varna hierarchy (Vaishya). The third candidate is Sanjay Singh, a longtime party functionary responsible for organisational work in several states and elections.

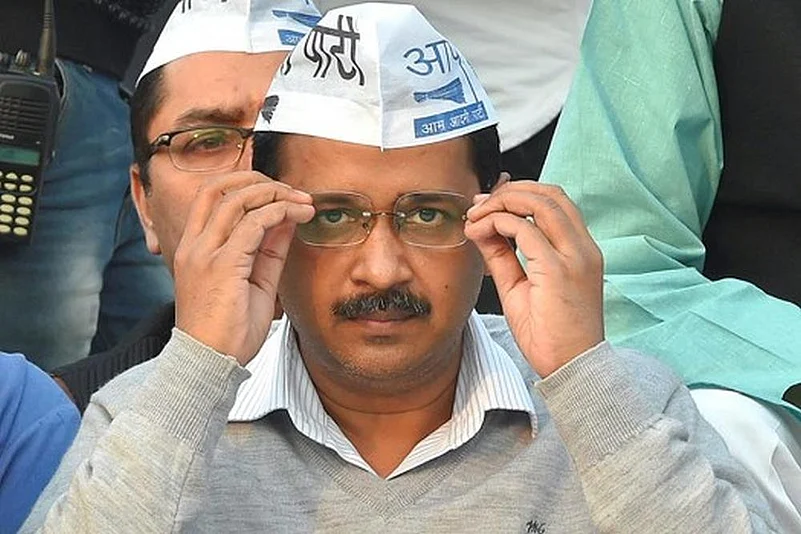

Perhaps the two men at the centre of this controversy only happen to belong to the varna category that is among the most prominent social groupings in the northern belt—and the same varna as the Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal. Yet, just the symbolism of this selection has invited a lot of flak upon the AAP. Not just from outside but there is a feeling of resentment within the party as well.

This is because AAP has always claimed to be a party with a difference but as things stand, the party that speaks for pro-poor causes has not fielded any big social activist for the Rajya Sabha. It says it stands for the Muslims and yet it has not chosen any Muslim candidate either. It says it represents the aspirations of Dalits. However it has also not picked a Dalit candidate.

The AAP has won not one but two elections in Delhi, quickly doubling its vote share to over 54 per cent in 2015. This feat was largely accomplished by the Congress voters’ shift toward the AAP, since the BJP’s upper caste vote bank had stayed intact. According to the 1991 Census, SCs make up 19 per cent of Delhi's population, as compared with 16 per cent nationally. Across Delhi's Lok Sabha constituencies there have been wide shifts in demographics. The population of OBCs now varies from 15 to 50 per cent in Delhi from area to area. Within the 67 Assembly seats it won in 2015, the AAP had won all of Delhi’s 12 reserved constituencies. This indicates that while people from all social groups voted for the AAP, the SCs and OBCs, by sheer dint of numbers, were a big chunk of its voters. Hence, some argue that the AAP should give wider representation to the Dalits and OBCs.

However, the AAP’s key leadership positions remain with non-SC and non-OBC leaders. The deputy CM Manish Sisodia is a Rajput, for instance. The speaker Ram Niwas Goel is a baniya, though the deputy speaker Rakhi Birla is a Dalit. The Delhi Dialogue Commission is headed by the CM but the vice chairperson is another Vaishya, Ashish Khaitan. Delhi's planning board is headed by the minister of planning, Sisodia.

The Dalit minister Sandeep Kumar has been evicted from the party (and now supports BJP). In his place is Kailash Gahlot, a Jat, who is minister for administrative reform, law and transportation. The cabinet therefore has one Dalit, one OBC, and a Muslim minister other than a Jain, Bumihar, Rajput and a Bania. Conspicuously absent, therefore, is a woman cabinet minister.

It can be said that what has happened in AAP is one of the big conundrums that plague most mainstream political parties. They want Dalit, Muslim and women voters but are unable to create leadership within the groups that they woo during elections. In the present environment, of heightened awareness of gender, caste and religion, AAP’s selection of a Rajya Sabha candidate could have been a great opportunity to trumpet its pro-justice credentials.

The fact that there is no Constitutionally-mandated reservation for members of the Rajya Sabha, is not being seen as a stumbling block before a party with an overwhelming majority in the Assembly. Of the 250 members of Rajya Sabha, of whom twelve are nominated by the President, the rest are indirectly elected by parties. This means that the terrain was wide open for signalling gender and caste equity. Yet, AAP has not opened those doors, leaving it to battle the charge that it has Dalit votes but no Dalit representation, and so on.

This is all the more damning for AAP had itself created a narrative of trying to seek out candidates from among the very best in public life. Ultimately, its selection is a disappointment and seems like a comedown. The party says that it failed to convince any of the 18 people it approached for these seats. This in itself says a lot about the pitfalls in Indian democracy. People, AAP deputy CM Manish Sisodia has said, are petrified by the central government and do not wish to take it on in the Rajya Sabha. AAP’s reputation for taking on the central government has, it says, repelled even the eminent in society from accepting these offers—including a former Chief Justice, a top advocate and an opposition leader who has himself been outspokenly against the BJP.

Seen in this light, it says something about the two businessmen picked by AAP, to have accepted the positions in Rajya Sabha (pending their election, which is set to be a shoo-in). Sushil Gupta, one of the candidates, is said to have some standing in Haryana, particularly among the community of Agarwals, which may help the party consolidate its position in the neighbourhood. Then again, ND Gupta, a chartered accountant, has assisted AAP in numerous litigations. The question is whether these are good enough reasons for RS membership. That the two candidates are from the trader or bania community, may also reflect the AAP’s larger strategy, considering talk about the community’s growing rift with the BJP, which has being wooing a larger array of social groups.

The AAP had decided not to name Kumar Vishwas, a PAC member, though he had lobbied hard, signalling a trust deficit within the party. Vishwas is understood to want the party to move towards what is loosely called Right Wing Secularism, in opposition to BJP’s Right Wing nationalism, locking him in a ideological tussle with AAP. Now, there is a question of whether Vishwas would flee the party. AAP’s inability to handle heartburn and tussles indicates not just its failure at inclusivity. It shows that the party is unable to melt together different streams of thought, winning over dissidents. Vishwas, with Bhagwant Mann, was one of the stars of the party's campaign for the 2015 elections. Both had addressed as many meetings as Arvind Kejriwal.

AAP also didn't want an organisational person in its Rajya Sabha list, for they were wanted for electoral contests. The party thus projected a search for an imminent outsider to take on the central government and speak out on issues important for the nation. Some of the 18 people it approached felt that accepting AAP’s offer would affect their own independence. One was told by his spiritual guru to decline. Yet, ultimately, the persons selected after creating high expectations are not even the face of the opposition. Charitable work, as done by Sushil Gupta, does not add to credibility beyond a point. In a way, AAP is simply wooing a community that has been distancing itself from the BJP ever since demonetisation while in no way living up to its idealism. This is a reason for growing resentment within the party now.

Even if there is nothing untoward in these selections, AAP risks being seen like any other formation. AAP leaders often say that their party lets its pro-people works speak for themselves. Underlying this is the premise that no party can survive on being just the party of the poor. The argument is that if AAP did not even exist or if it is voted out, then there would be not idealism for them to be measured against.

For AAP, whatever it may have lost during this brouhaha, it may have gained another dissenting voice in Ashutosh, who alone voted against one of the candidates proposed by the CM. Whether he will be targeted next—who knows?