“In the room the women come and go, talking of Michelangelo” - TS Eliot.

The stench of rotting blankets, rat litter and woodsmoke meets those who enter the subdued gate of the ‘rain basera’ in Delhi’s Sarai Kale Khan. “Rain Basera” literally translates into “night shelter” - a refuge for the night. But in this 'rain basera', the homeless have been living in a permanent state of transcience for many nights.

Photo Gallery: People Throng To Shelter Homes As Cold Wave Sweeps Delhi

38-year-old Lachmi had lived all her life in the underbelly of flyovers. At first, she lived under the flyover at Modi Mill. Then she moved to live under the Ring Road Underpass. Having lost most of her family members to unknown diseases, Lachmi who picked garbage for a living remembers the day she became a mother. "I was filled with terror for the life that was waiting for this little one," she recalls. Her fears were not unfounded. Lachmi's firstborn passed away. "Khatam ho gaya," she said. "He was done". She cannot recall what disease took him. "We lived on streets. Who knows what happened to him. He was just dead one day". Some years ago, however, Lachmi, who had by then given birth to a daughter, was told by city authorities to move to a new building that had been designated just for people like her. A night shelter for the homeless.

(Lachmi with her two children inside the night shelter at Sarai Kale Khan | Photograph by Tribhuvan Tiwari)

On the intervening night of Tuesday and Wednesday when the temperatures dropped below four degrees celsius - well under the average in the city at this time - Lachmi was swathed in lice-infected blankets discarded by the more privileged. She complained about the lice but was thankful to have three blankets for her and her three children. Lachmi has been a permanent resident of the night shelter for four years now. It isn’t ideal. But at least, it’s home.

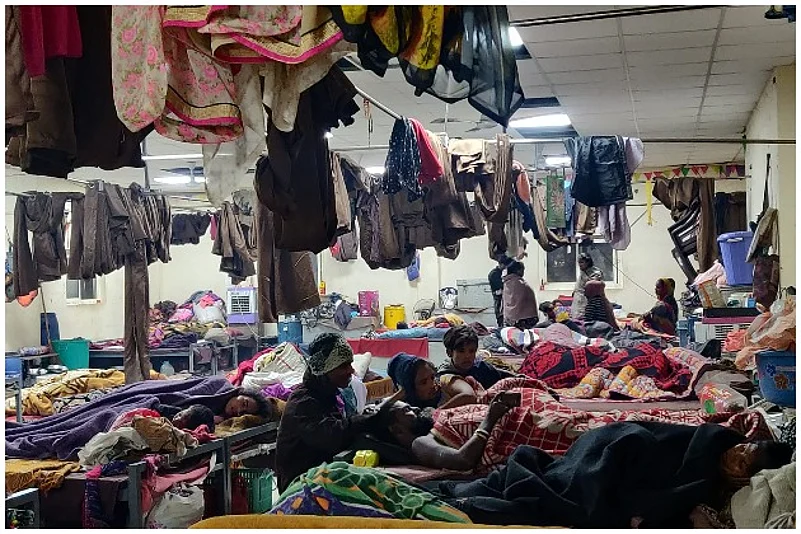

(The Sarai Kale Khan night shelter was packed this week amid cold wave | Photograph by Rakhi Bose)

Lachmi is one of the 500 odd residents that fill up the cavernous rooms of the night shelter, located at a hair's breadth from the bustling Nizamuddin Railway Station. The complex is divided into seven parts including six permanent buildings and one temporary tent that comes up during the months of November to March to accommodate the growing influx of the homeless as the mercury drops. A common courtyard in the middle is used by inmates for cooking, washing, and general socialising.

Permanent roommates

Tuttru came to Delhi five years ago from a small village in Rewa, a district in Madhya Pradesh with 50 per cent more poverty than the state’s average. He had just married Rita and wanted to give her a good life. But finding work was not easy. “We left when the pandemic hit the first time but came back. We left again during the second wave, but came back again,” Tuttru says. “We have a home in the village but no money or job. Here, there is some money but not enough to get a home,” his wife chimes in.

(Tuttru and Rita live on a khatiya with their family of four | Photograph by Rakhi Bose)

Rita and Tuttru have spent much of their married life on a khatiya in this rain basera, along with their four children. The youngest has colic and cries constantly. While there is a medical wing in the shelter, the doctor comes just twice a week. “In some weeks, he doesn’t come at all,” Rita adds.

On the khatiya beside Tuttru’s lives Babita Devi who yearns for some privacy. The beds of the inmates in the rain basera are separated by tall curtains, offering a semblance of rooms. Babita, however, said that curtains were no match for smells. “Many here don’t clean their own areas. Their kids poop and urinate on the covers, dogs and cats walk inside and defecate under the beds”. Babita said that though the rooms were cleaned once a day, the stench remained.

(A 'room' in the night shelter separated by curtains displays signs of faith and life | Photograph by Rakhi Bose)

There was also the issue of toilets. The complex has a total four toilets each for the men and women and two bathrooms. “There are over 300 people here at any given time. The bathrooms are used not just by all of us but also by people from the 'jhuggi' outside. They are always full,” Babita says. She worries about her 15-year-old daughter’s health. “Young girls need space and privacy to grow and clean bathrooms, especially during periods. The bathrooms here are rarely cleaned”.

Jyoti, another migrant worker from Bihar who is employed as a cleaner by the shelter home authorities, said that they do their best. “There are just too many homeless people,” she exclaims.

Ankit Kumar, 29, who has been working as a caretaker at the shelter home for the past three years, agrees that the number of homeless people had been increasing in the past few years.

(Jyoti (right) with her daughter Ishrat | Photograph by Rakhi Bose)

“We have a mix of everyone here. People who lost their jobs and couldn’t afford rent anymore after the pandemic, migrant workers who never found a home, visitors coming to town for short-term work, and of course, Delhi’s permanent homeless,” Ankit said.

Where do the homeless go?

Ramesh, who has been living at the shelter for three days now, says that he had visited several shelters in Delhi before coming here. “They were either cramped or full capacity or not accepting any fresh inmates,” he said. A migrant worker from Uttar Pradesh, Ramesh was a labourer and usually slept on the streets near Jasola. This year, however, the cold was too much.

(While 'permanent' residents find 'khatiyas', the transient manage with just blankets | Photograph by Tribhuvan Tiwari)

There are over 200-night shelters in Delhi. Earlier this month, Delhi Home Minister Satyendra Jain announced an initiative to rehabilitate the capital’s homeless people into shelter homes across the city during the winter season. The Delhi Urban Shelter Improved Broad (DUSIB) said they have added more 277 beds in the capital for the winter months. While the original capacity of the shelters was 19,640, the pandemic and social distancing protocols have brought the number down to 9,006. The network of shelters reportedly supports 25,000 homeless people every winter. Since the cold wave hit earlier this week, winter shelters such as the ones put up in Kashmere Gate were running full to capacity with no beds available. Since October 30, DUSIB rescue teams have shifted 2,594 homeless people into shelter homes. As per data reported by DUSIB, 6,702 people stayed in the 206 rain baseras of Delhi on December 12.

(An intense cold wave gripped parts of north India last week with minimum temperatures in Delhi dropping to 3.2 degrees celsius | Photograph by Tribhuvan Tiwari)

While some like Ramesh were flyby visitors, others like Lachmi, Tuttru and Babita have found in these night shelters and unlikely haven. However, according to Census reports, Delhi has over 46,000 homeless people. Which itself, according to activists, is a gross underestimate. Are the shelter homes enough to provide space to all? For Rama, who currently lives under the Yamuna Bridge with her children, shelter homes don’t mean the end of destitution. “I have gone and lived many times in shelter homes but always faced problems. There is a lack of hygiene in many, space crunch, even theft. I feel more at home here under the bridge,” she asserts. But how does she keep warm? "We all know how to build woodfires," Rama smiles.

Meanwhile, back inside the shelter, 8-year-old Viraj who is a fan of superhero films and wants to watch ‘Spiderman: No Way Home'. The film was recently released in theatres and Viraj found out about it from other kids in the shelter home. His mother, Babita Devi, laughs. “No way home? We have no home too. Maybe Spiderman should also live in a shelter home like us,” she jokes.

(Babita with her son Viraj, who is a fan of Spiderman, has not gone to school in nearly two years since the start of the pandemic. Babita cannot afford tuition or online classes for him| Photograph by Rakhi Bose)