The Joys of the Literary

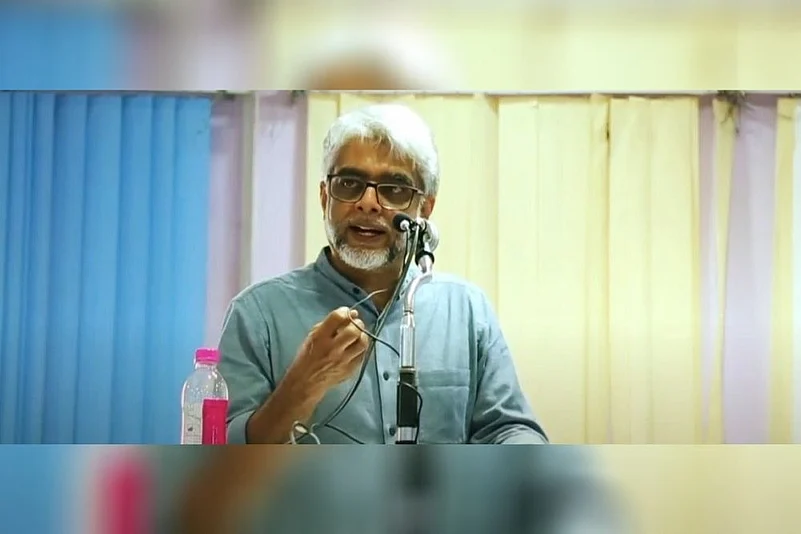

In spite of having come to learn that the study of literature was accommodative of a host of “texts” ranging from novels to films and paintings to cultural phenomena, my confusion regarding the precise meaning of the adjective “literary” persisted until the end of my graduation days. The year was 2012. Feeling half-foolish and half-expectant for some clarity, I posed the problem to Professor Udaya Kumar, my then MPhil supervisor at Delhi University. And there came an illuminating response in his characteristically calm manner. “Literary,” Kumar replied, “is that which evokes pleasure upon studying something.”

The professor’s statement stuck with me. It wasn’t so much a dry, clinical truth as it was a perspective that cut across the binaries of high and low, popular and classical literatures, which acknowledged an experience that any person with basic readings kills was capable of having: a literary experience. In highlighting the role of pleasure, Kumar eased my growing frustration with a global academic tendency that tirelessly promoted a cynicism – even hatred– towards literary texts in the name of “critical thinking.”

As Jon Baskin wrote in an essay intriguingly titled “On the Hatred of Literature” earlier this year, “Our professors had a great deal invested in novels and poems; and it was probably even the case that, at some point, they had loved them. But they had convinced themselves that to justify the “study” of literature it was necessary to immunize themselves against this love, and within the profession the highest status went to those for whom admiration and attachment had most fully morphed into their opposites. Their hatred of literature manifested itself in their embrace of theories and methods that downgraded and instrumentalised literary experience.”

Not so Kumar, and thank heavens for that. In spite of being astonishingly wide-read and theoretically proficient, instrumentalisation never marked his pedagogy or politics. He was, and remains, a rare phenomenon in the world of literary studies.

A Pedagogic Excellence

I first met Professor Udaya Kumar during my MA, a course I hardly enjoyed owing to its intensely impersonal environment. Even so, Kumar’s lectures made a unique mark amidst all the unhappiness, and I decided that should I do an MPhil, it would be under him. At a time when I was just beginning to realise that not all good scholars made good teachers, it was a

joy and relief to come across the gentle and gracious expertise of a professor like Kumar, who embodied the best of both.

A steady cadence suffused his lectures that never devolved into monotony. His enunciation was effortlessly buoyed by a quiet assurance that only comes with the deepest familiarity with one’s discipline. Often holding no more than a single sheet of paper to collate his points, Kumar’s analysis of the text at hand took the form of an elegant oral narrative, which was in equal parts politically astute, philosophically revelatory, and aesthetically enriching.

This was a balance that enthralled me, for it made me realize that ideological interpretations and form-appreciation could go hand in hand, generating enthusiasm and wonder. When I finally made it to my MPhil under his supervision, he ensured that this wonder never waned, even as he simultaneously shepherded me towards the precision of thought and expression. For someone who excelled in areas as wide as Modernist studies, theory and criticism, Indian literatures and aesthetic philosophy, Kumar wore his wisdom lightly and courteously.

My most significant and special association with the professor grew in the form of my dissertation topic, which focused on the literary-visual evolution of Shimla, my adopted Himalayan hometown. Always appreciative of my area of study, Kumar intricately guided me towards Shimla’s evolution in terms of the place’s “history of perception.” This was another phrase that I learned through him. That the emotional act of perceiving could itself be thought about in a historically changeable manner was a thrilling proposition, because it attuned me towards the town’s minutest cultural shifts whilst simultaneously keeping me conscious of the general picture.

Landing in Cambridge a few months later with the help of Kumar’s reference to pursue further qualifications, I continued to think through his teachings. Before leaving for foreign shores, when I proposed a complete shift in my field for my doctoral work (fantasy literature), not once did he doubt my intentions or calibre. But even as I delved into my new area, I kept building on my former research. Kumar’s role as a supervisor had instilled a confidence to continue with my previous interest in an individual capacity, and this, unarguably, was one of his finest gifts as a teacher: the birthing of a steady intellectual assurance in his student.

Despite my PhD topic bearing no ostensible relationship to Kumar’s academic output, I regularly visited his works to explore refreshing ways of academic meditations, which, for all their complexity, steered clear of verbosity and blanket judgements. Instead, his reflections created probing conversations amongst authors, theorists, and readers, and this emphasis on dialogue could also be seen in his politics, whose most recent instantiation emerged in the form of his unstinting support for Professor Hany Babu and his work.

And just as Kumar unambiguously lauds the work of his contemporary, he himself is esteemed for collective endeavours. One of the other abiding memories from my MPhil is of Professor Alok Rai inviting Kumar to his course for rigorous intellectual exchanges, each stalwart enthusiastically absorbing ideas from the other.

The Death of Decency

When I first learned of the recent misbehavior meted out to Kumar by the JNU Executive Council, which unjustifiably denied his leave for a prestigious fellowship in France, it came as a shock but not much as a surprise, given the current climate of country-wide authoritarian highhandedness. After months of harassment, the professor moved the Delhi High Court, which not only gave a judgment in his favour but also awarded him the money in costs.

TV anchor Ravish Kumar has increasingly argued that our countrymen who senselessly desire to become a “vishwa-guru” (“teacher of the world”) should first look into the deplorable plight of our own gurus. Among the many ills plaguing the profession of teaching, “uncivility” ranks high, a trait that is fast becoming the hallmark of our society, as the social commentator Santosh Desai has recently observed. In our evolution as a nation, we have somehow forfeited the importance of behaviour as “unnecessary” or “merely cosmetic.” George Orwell’s words thus come to mind, who said that “If men would behave decently the world would be decent.” Learning from Kumar’s unwavering decency may well be a good place to begin with.

(Views are personal)

*Siddharth Pandey is a writer, photographer and curator who has published widely in academic and popular platforms. Currently, he is writing two histories of Shimla. He can be found on Instagram @shimlasiddharthpandey