In the year 2024, we will be talking a lot about duets in Punjabi music. Do-gaana: two singers singing.

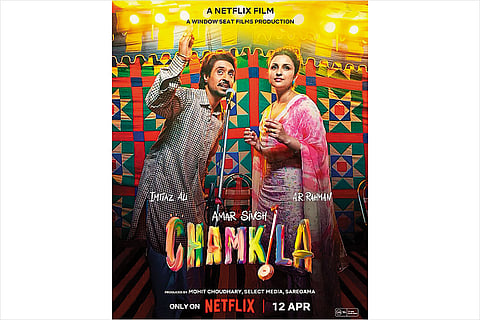

Not So Shining: The Reality Of 'Chamkila Phase'

Amar Singh Chamkila may be celebrated, but many of his songs are blatantly sexist

Back in 1960, a little over a decade after Punjab was recovering from the trauma of the Partition of 1947, Mohammad Rafi and Shamshad Begum sung what is perhaps the most popular and recycled Punjabi duet for the movie Do Lachchiaan. It now enjoys cult status. The song has become an integral part of every celebration related to Punjabis across the globe.

‘Teri kanak di raakhi mundeya, hun mai nahin bendi’’

(Boy, I will not guard your wheat fields)

In this duet, when Mohammad Rafi replies to Shamshad Begum, the only three words used for the girl are ‘balliye’, ‘kudiye’ and ‘jattiye’. Written masterfully by Verma Malik (born Barkatrai Malik in Ferozepur) and set to the composition by Hans Raj Behl, the lyrics are about a farmer boy and his girl’s coquetry. The song features bucolic village life, birds (tittar, bater), desi months (jeth, haarh) and feminine decorations (mehndi, jhaanjar) embroidered around their flirtations.

“Mai dil tenu denda haan, tu kyon nahin laindi?”

(I am giving you my heart, why don’t you take it?)

She replies:

“Dil tera je lai leya mai, tu kahenga khoohte beh ja

Naal kahein baldaa nu tore, naal kahenga khetaanu paani de ja”

(If I accept your proposal, you will make me work in the fields.)

This is a crisp flirtation in which she is scared of the reality that comes after the initial phase of marriage–tough farm work. However, when the song ends, she does accept his proposal, thus agreeing to be the woman in charge of the wheat fields.

It is really intriguing how the language of the duets, which was dewy in the 1950s and 1960s, changed to the ones heard in, around, and after what can be called the “Chamkila phase” of Punjabi music. Today, there is a sustained effort to give a cult classic status to Chamkila (who ironically was the contemporary of popular singer/actor Gurdas Mann), but have people actually heard him?

Consider this:

“Satt din sahuriaan de ghar rehke aayi,

Phulljhariye nihun fire kamlaayi,

Aatte vaangu gunnti begaane putt ne.”

This song is an extremely brackish and vulgar remark on connubial bonding. It talks about the boy kneading the girl like dough. Kneading the girl like dough? The woman who had accepted the status of the guardian of the wheat fields in Punjab and Punjabi music has now herself become the dough to be kneaded by begana putt (someone else’s son). Here it refers to the husband of the newly wed. The song suggests that the husband knead his wife like dough. Whatever that means!

In another duet by Amar Singh Chamkila and Amarjot Kaur (sung by Diljit Dosanjh and Parineeti Chopra at the trailer launch of the much-awaited biopic on Chamkila directed by Imtiaz Ali), the girl is titillating the boy:

“Mainu chatt lai tali de utte dharke, ve mitra mai khand ban gayi”

Here, the woman is asking the man to lick her because she has turned into sugar. In another song, they talk about the metamorphosis of a young teen girl into an older woman at the tender age of 16 who the boy needs to parakh. To try and test her. There is another one, “ran kutt ke sidhi na keeti”, which advocates that a man who does not beat up his wife is not a real man.

This transmutation of the lyrics is what Punjabis are now going to celebrate (or debate) as ‘the great’ of sadda music. Sadda sabhiachaar (Our culture)!

Around the talk of the movie on Chamkila’s life, the people en masse are slipping (or being made to do so) into collective amnesia about the greatest heights of Punjabi music and poetry. A group of people has become very vocal in pushing the whole society into a concerted ‘‘rediscovery’’ of Chamkila. This group is omnipresent, especially on social media and YouTube. Surprisingly, it includes people from both the rural hinterlands (who are conservative when it comes to their own women), and the ones with the post-graduate degrees who want their own women to take up respectable professions, and would not tolerate anyone singing the above songs for them. They want their women to thwart all untoward advances of men. If you are not observant enough, this group will make you erase everyone else from the Punjabi music scene except the do-gaana singers of the 1970s and 80s. They try very hard to portray Chamkila and his partner Amarjot Kaur as the ‘saviours’ of Punjabi music!

This group says that Chamkila uncovered the dirt of Punjabi society, suggesting that the society is indeed very ribald and that he was the voice of the masses (while people thought the masses always took pride in talking about rescuing women captured from as far as Afghanistan). They also swear that Chamkila was the folk voice of Punjab (Yamla Jatt/Surinder Kaur, anyone?)

Ironically, these same people will say that Chamkila’s songs are not meant to be played before families. His songs are for the motors and the tubewells in the fields in village outskirts, or now, as the times have changed, in the hostel rooms that are far away from everyone else. A ‘great’ who has no place among respectable families and relatives!

Almost all the die-hard fans of Chamkila are men. We know of few women or girls who listened to these songs. No woman can say proudly that she is a Chamkila fan.

When it comes to the voice of Punjab, the popularity of any song in rural Punjab is measured on the basis of two factors: How often is the song played in weddings (wedding ‘palaces’)? How often is the singer or the song heard in public or private buses?

We have never heard his songs being played by DJs at weddings or on buses. I do remember some of the most amusing lyrics heard on public transport buses crooned by little- known singers–tere viaah di Maruti agge marna, main dhidh naal bamb bann ke/tere viaah di CD nimaivekhi, gwaandiaan de VCR te (I’ll die in front of the Maruti in which you got married/I watched your wedding movie on the neighbours’ VCR—envisioning one home in the village where everybody went to watch the wedding movie on the good old VCR with the heartbroken, rejected lover watching it silently, too). How does one even digest the gist of these lyrics?

The only thing which can be agreed upon is that Chamkila was not the only one adding raunchiness to lyrics. The majority was doing it on both sides of the border in that decade but it is to be noted that they have been forgotten too. They did not get any respect for robbing the language of dignity.

The defenders of Chamkila will not even admit the obvious these days—that there has been a steep decline in the degree of lyricism in Punjabi in popular music from the Chamkila phase onwards. The man is still a munda or a gabhru. Among the masses who otherwise refer to the women as ‘Kaur’—the princess—the woman is now talked about as patlo, nakhro, naar, rann, rakaan, patlelakkvaali, tikhenakkvaali, phulljhadi, etc. The wedding dhol and dholki are bystanders to the newly-wed husband dancing with his wife to the sounds of ‘‘patlo/nakhro’’. Oh, we all dance to it! However, even as ‘‘patlo/nakhro/rann’’ deafen people at the wedding ‘palaces’ in both rural and urban areas, one sees that Chamkila and Amarjot are not to be found there.

It is interesting to note that while the most popular duets etched on conscious minds do not belong to Chamkila, there is a vigorous attempt now to legitimise what he stood for. He is being portrayed as a martyr or a victim of the system, and that could be true. He could have been a victim of the political system, or of professional jealousy, or of something else we don’t know much about. However, his songs cannot claim to have a pristine place in either Punjabi culture or music. About the emotional exploitation of his name, it needs to be stressed that it is not him, but his lyrics that are being validated for the younger generation.

Chamkila and Amarjot’s assassination was unjustified. No one’s life should ever be taken away unnaturally and prematurely of course. It is also possible that had the two lived for long, they would have become irrelevant. They were a passing phase which would have faded simply because of the phenomenon of transience.

A lingering question remains: why did Chamkila become so popular in the years when Punjab was dealing with the dark days of terrorism, disappearances, and many families migrating for myriad reasons? The psychology of trauma could explain that.Trauma has strange manifestations. One such manifestation of the shared societal trauma of that time was Chamkila’s popularity. People were not scared to call him (and Amarjot, the woman singing equally bold songs) for wedding shows in villages or stage performances abroad despite the fact that he was flagrantly controversial. Had people become so numb to pain that they were de-sensitised to the lack of morality in the music? What could be worse than families living under the shadow of the gun? Morality is a virtue of prosperous and healthier times. One should not expect it from people suffering in their own land.

However, trauma too does not justify the forgetfulness towards the duet which has lasted for more than half a century now in various forms and remixes, and refuses to die as it watches the khand get the sponsorship of the biggest names of the tinsel world in the season of wheat. Rest in Peace, Vedraj Malik and Hansraj Behl, for giving us ‘‘teri kanak di raakhi mundeya, hun main nahin behndi’’. Rest in peace, Mohammad Rafi and Shamshad Begum, for what is perhaps the longest living do-gaana rooted in the soil.

Kanak in Punjabi means wheat and khand means sugar. Wheat will remain wheat. Sugar cannot replace it. Wheat feeds the armies, while sugar is a taste laden in controversy. Sugar may be sweet, but it is not healthy. Happy Visakhi (Baisakhi) week in celebration of the wheat harvest, and Khalsa sirjana diwas–sadda sabhiachaar!

This appeared in the print as 'Not So Shining'

Ramandeep Kahlon Sangha is a Nephrologist based in New Hampshire, USA