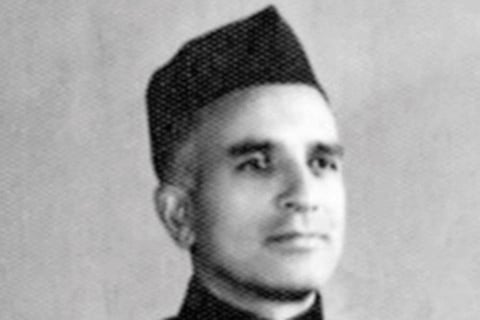

A few months before the events of 1989 would irreversibly transform the course of Kashmir’s history, my grandfather, Pandit Rughonath Vaishnavi, was a slightly embittered 79-year-old man, and yet not hopeless. A lawyer and political activist, he closely tracked what Russia’s retreat from Afghanistan, and the end of the Cold War, might signal for Kashmir and its future. One morning he woke me up to accompany him on his morning walk. Fearful of the fate that awaited all Kashmiris, he hoped that the shifts in global political trends might convince his fellow Pandits to reassess their politics vis-à-vis Kashmir. Perhaps they too could join their Muslim counterparts to demand an urgent and just resolution of the Kashmir issue based on people’s collective will? Earlier that morning he had drafted a statement of solidarity and was hoping that some Pandit neighbours might sign it. Aware of how he was treated by members of his religious community who considered the Kashmir issue long settled and failed to portend the violence that would soon throw the entire valley into deep despair, I was predictably a little reluctant to walk with him. We returned home without any signatures.

The Pandit Across The Lidder

Rughonath Vaishnavi gave over his life to Kashmir’s demand for self-determination. Voices like his, founded on a democratic impulse, muddy India’s neat narratives.

Vaishnavi’s political activism in Kashmir began in 1928, as part of the Indian independence struggle. As a young freedom fighter, barely out of high school, he became a vocal critic of socio-religious institutions that sanctioned divisions based on “religion, caste, and country”, a philosophy that informed much of his subsequent, albeit brief, association with other Kashmiri labour activists such as Kashyap Bandhu and Jiya Lal Kilam. Together, they worked to reform Hindu customs that encouraged dowry, forbade widow remarriage, and promoted excessive ritualism. After a brief hiatus from politics between 1931 and 1938, during which time he studied political science, psychology, and law in Lahore and Allahabad, Vaishnavi returned to Kashmir in 1938.

The 1930s in Kashmir was a decade of grave repression, but also of hopeful optimism. The nationalist ethos had been stirred by the events of 1931, when 21 people were killed by the state police during a protest march against the arrest of Abdul Qadir, who had dared to openly condemn the Maharaja’s despotic rule. When Vaishnavi returned to Kashmir in 1938, the Muslim Conference headed by Sheikh Abdullah had just changed to the National Conference (NC), with Premnath Bazaz as the first non-Muslim member of the NC working committee. Vaishnavi too joined the party in 1941, a year after Bazaz resigned because of his political differences with Sheikh Abdullah.

Read Also: Homeward Diary

Perturbed by the growing violence and hooliganism of the NC workers, and worried that NC’s secularism was a foil for the party’s “One leader, one organisation, and one slogan” diktat, Vaishnavi left the party in 1943. Emboldened NC workers, he writes in his journals, would harass Pandit shopkeepers, jeer at members of the J&K Muslim Conference, and, during NC’s rule between 1947 and 1953, arrest or detain people “for whispering in their minds their desire to accede to Pakistan or opt for independence of the state”. It was clear that Kashmiris were denied their “civil liberties, and freedom of press and platform”. In order to highlight the repressive policies of the ruling party, Vaishnavi drafted a statement for the UN representative, Sir Owen Dixon, who visited Kashmir in 1950, which was endorsed by a group of Muslim and Pandit comrades, including J.N. Sathu, Mir Noor Mohammad, and Shyamlal Yachew. (The statement was published under the pseudonym ‘Ghulam Qadir’ in the September/October issue of the Radical Humanist.) Soon after, the Urdu newspaper, Jamhoor (demos), which he had started with Mir Noor Mohammad, was banned by the government.

The repressive policies of the NC had stifled all forms of opposition, and purposefully prevented a robust dialogue on Kashmir’s political destiny. In 1953, Vaishnavi, along with G.M. Karra, formed the Political Conference, a party that called for a free and fair plebiscite and championed Kashmir’s inalienable right to self-determination. To silence this critical voice, Vaishnavi was arrested along with several of his colleagues, and he was not able to petition for a writ of habeas corpus because the fundamental rights charter written into the Indian Constitution was not extended to the State of J&K at that time.

In December 1963, the disappearance of the Holy Relic from Hazratbal shrine in Srinagar led to widespread protests by Kashmiris of all faiths and political leanings. For Vaishnavi, who had spent five years in jail in the 1950s for resolutely demanding Kashmir’s permanent resolution through a free and fair plebiscite, the uprising was not a fleeting or an inconsequential episode. Although triggered by a religious transgression, it represented a broader political crisis in the state and the deep-seated resentment of Kashmiri Muslims against Indian rule.

The uprising, he notes in his daily journal, had remarkably united Kashmiris, regardless of their religious affiliations: “Muslims shouted Hindu dharam ki jai and Hindus shouted Allah-u-Akbar and Islam Zindabad.” Vaishnavi writes that this solidarity was short-lived; a majority of Pandits continued to believe in the finality of Kashmir’s accession to India despite its legally contractual nature, and seemed unmoved “by the high impulse of political cohesion with Kashmir’s Muslim body politic”. For them, “the present [political scenario] was just as an ordinary matter,” and they expected that a “miracle [would] set it right”, or that Nehru would once again succeed in “retaining Kashmir under his iron heel”.

For Vaishnavi, the Kashmiri Muslim demand for a free and fair plebiscite was a pledged right, not a “gift or a concession”. While most Pandits refused to acknowledge these rights, he worked tirelessly to ensure that India did not renege on the promises made to Kashmiri people, or thwart their fundamental right of self-determination as enshrined in the UN Resolutions of January 13, 1948 and January 5, 1949.

It pained Vaishnavi to see that India’s independence had failed to end Kashmir’s decades-long subjugation. In his unpublished memoir, he claims Kashmiris had been “relegated to the position of slaves” after India’s independence in 1947. To him, denying Kashmiris the right to choose their political fate was a “colossal failure of [humanity] and statesmanship”. Decolonisation, he argued, had made democracy a “cherished ideal of every emerging nation”, and Kashmir could not be held back from “her rightful place in the comity of nations”.

Through his papers and journals I can see how my grandfather’s story muddies the neat narratives about Kashmiri politics that have become a staple in India’s public sphere. Whether or not we agree with the perspectives of political activists such as Rughonath Vaishnavi (or Premnath Bazaz, who too emphasised Kashmir’s provisional accession to India), their mere existence destabilises dominant narratives that track the Kashmiri struggle for self- determination to “Islamic religious radicalism”, or to the precipitous events of 1989 alone. Such political figures make it impossible to erase Kashmir’s long history of political struggle and repression of fundamental human rights that predates 1989. Their stories challenge our preconceived notions about history, religion, nationalism, and politics in Kashmir. In their lifetime and beyond, their political writings and commitments were belittled by those who refused to see past their blighted visions. Vaishanvi was derided as a Pakistani Butta (Pandit); even his Pandit comrades such as Advocate Jiya Lal Kilam, who he had worked with as a social reformist, “considered him a persona non grata” for his unwavering stance and commitment to Kashmir’s right to self-determination.

Vaishnavi remained unfazed, and continued to claim that the Kashmir issue, if left unresolved, would “vitiate the social climate with fear, distrust, hate, spite, animosity. A catastrophe may befall the subcontinent. And the tear [would] be terrific and damaging beyond repair”. And yet, his repeated pleas for an urgent settlement of the Kashmir issue in accordance with people’s aspirations fell on deaf ears. Instead, what continued and assumed draconian proportions after the 1990s was the criminalisation of dissent, the silencing of political opposition, and the crushing of representative democracy.

Under the pretext of combating Islamic terrorism, India has conveniently ignored the complexities of history; it has also shunned its legal and moral obligation to correct its political course in Kashmir. As I read and re-read his journals and prison diaries as well as his repeated pleas to national and international dignitaries, asking them to resolve the Kashmir crisis, it is clear to me that for Vaishnavi the struggle for Kashmir’s independence was a struggle for truth and justice. I cannot help but wonder how a just and honest political approach would have led Kashmir, and the rest of the subcontinent, on a different path.

(The author is associate professor of anthropology at DePauw University, Indiana, US)