The whiteness of night frees itself from poetic exaggeration as the winter moon licks the snowy Shivaliks, swamping the undisturbed landscape with crystalline bleach and creating a stage that no studio mood-lighting can capture. A freeze frame; it’s the kind of yarn that travel brochures spin. In a village under that wispy moonlit glow, no mortal worry disturbs the sleep of a hardworking family inside their wooden cottage built with timber harvested from native trees, the close-fit mortise and tenon hewn with hand tools exhibit woodworking skills passed down generations. The cob caulking keeps off the howling wind’s nightly trespass, the wood stove keeps everyone snug and toasty in their woolly blankets. But something goes wrong—the tin heat barrier behind the fireplace buckles and the exposed logs catch fire.

A Fire-Breathing Winter Monster

House blazes are fire-and-brimstone moments in the hills—a burning issue that repeats every year but poor reportage leaves the victims out in the cold

Miles down in the valley, the telephone at the fire office makes a racket, a firefighter answers and looks out the window—a tiny sparkle, like fireflies phosphorescing on the hillside across. Ting, ting, ting ting…the fire-truck makes its way slowly on the switchbacks, dangerous and slippery from nine inches of overnight snow. There’s no snowplow to clear the road, the slightest mistake can send the truck into a fishtail and hundreds of feet down a gorge. They reach, but there’s nothing left to do or salvage. Whipped by powerful winds sweeping through the mountains, the fire made short work of the dry wooden house, sending the family on a headlong flight to safety through smoke and flames. Safety doesn’t qualify their situation—shelterless under a blanket of snow.

This is a recurring winter’s tale in the Himalayan states—little fires everywhere, repeating so often that these are seldom considered newsworthy unless a British-era landmark in Shimla or a popular shrine in Kashmir burns to the ground. These never make national headlines unlike, for instance, the 2016 forest fires during the pre-monsoon dry season in Uttarakhand when civilian and military personnel joined forces to create firebreaks and hovering helicopters dunked smouldering trees. So, what make house fires in winter a burning issue? It’s the sheer volume of cases. Around 600 houses, cattle sheds, outhouses, temples and government offices catch fire each winter in Himachal Pradesh: from Shimla to Kullu, from Mandi to Chamba. The figures are from a single state. Add two more hill states from northern India and those in the Northeast.

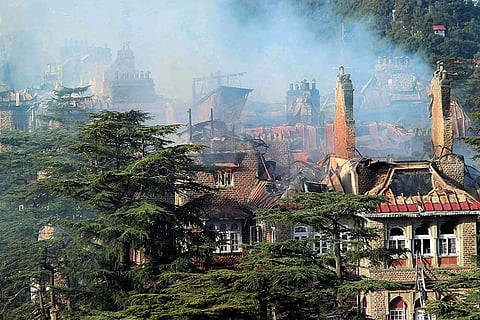

They Paved Paradise, Put up A Parking Lot The Grand Hotel in Shimla burns in 2019

The reasons vary—either accidental or mostly becuse of negligence. Electrical short circuit, faulty power lines, unattended candles and fireplaces, electric heaters, cigarette/bidi stubs, lightning…the list goes on. The financial loss runs into crores of rupees. The heartbreak cuts deeper—a family loses its home, its only home, when the days are dreary, the nights ghastly. Take two recent instances. On the night of December 11, a house on Melrose Compound, Mallital, Nainital, was reduced to ashes and three more were affected. In Gujandali village of Jubbal-Kotkhai—Shimla’s apple belt—a midnight fire consumed the four-storey, 20-room home of nine brothers and their families barely a fortnight ago. “Nobody died and the fire didn’t spread to the adjacent wooden houses in the thickly populated village that has more than 50 households. It could have been devastating,” says Shimla superintendent of police Mohit Chawla. The fires can have terrible consequences. In nearby Chopal’s Deha village, a fire in the early hours of November 26 annihilated the 18-room, two-storey home of Ramesh Verma and his brother Bansi Lal. Ramesh and two other members of the joint family died—he got trapped while helping the children and women escape. In November 2019, an elderly couple died of asphyxiation when a 117-year-old church and an adjacent house in the Meghalaya capital of Shillong caught fire. The cause—as in most cases—was a short circuit. That’s likely as repairs were in progress in the building, one of the oldest indigenous churches in the state, when the tragedy happened.

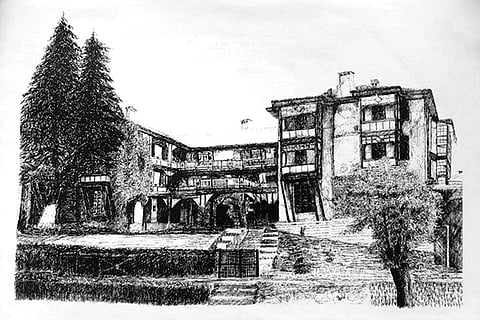

The parking space for MLAs where Kennedy House once stood, before a blaze razed the British-era building to the ground in 1991

Most of these mountainside houses sit on ledges—the lone access is a narrow walking trail or a raggedy set of stairs leading from the road. And most often the treks are snowed out and hardly visible. It’s hard to reach them on foot, let alone bring a fire engine within range of the hose. Safety guidelines are issued occasionally. “Villagers are encouraged to store water in local tanks and ponds for emergencies like fire in winter. General advisories are given out to check electric appliances, not to store firewood or dry grass or hay in homes and outhouses,” Mandi district collector Rughved Thakur says. In such treacherous territory, no insurance company covers these wooden houses. The hard-saddled farming folks scarcely know about insurance or afford to pay. Government aid, whatever little, comes wrapped with red tape. Delays are inevitable. It takes years for these families to rebuild their lost homes, slowly and painstakingly, dipping deep into their savings. “It’s like the world crashing down before your eyes. That causes the biggest psychological impact. We will not be able to come out of the shock,” says Chanderpal of Gujandali, whose house was destroyed by fire.

Heritage Lost

The timber-framed, British-era buildings bring that timeless spark to Shimla, the Queen of the Hills. But the tiniest of sparks—from an electrical fault or from the fireplace—kindles the most catastrophic fire that wipes out a piece of the hill town’s heirloom. Take Kennedy House, for instance. Built in 1822 and bearing Lt Charles Patt Kennedy’s name, the three-storey building had an embryonic link to the town—one of the first ‘pucca’ houses of the colonial summer capital. It stood next to the Vidhan Sabha and five government departments, including health and animal husbandry, had offices there. The house survived two major fires before, but the last one in January 1991 wrote its obituary. It was never rebuilt and an insentient concrete parking lot for legislators rose from its ashes.

All Smoke and Fire—The Gorton Castle, which was the accountant general’s office, went up in flames in 2014.

In four decades since, at least 100 buildings suffered a fire or two. The state secretariat, said to be the most protected with round-the-clock guards, caught fire in 2004. Unlike Kennedy House, it was saved. The list is exhaustive: Harcourt Butler School, now Kendriya Vidyalaya, the Viceregal Lodge, which now houses the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, the old Western Command Headquarters, the General Post Office and the US Club, Army Mess, the Vidhan Sabha library, the DC office, the DDU Hospital, the Himachal Pradesh University’s old building, Pari Mahal, Kumar House, Coop Printing Press, near Cart Road, Davicos…

Some are restored to their original splendour, most give way to modern brick-mortar unsightly structures, and many are lost forever. A military infirmary since 1954, the 1902-built Walker Hospital, was reduced to rubble in 30 minutes after a fire broke out on December 22, 1998. Rebuilding remained incomplete all these years. Peterhoff— witness to several pre- and post-Independence events, including Nathu Ram Godse’s trial, was damaged in a January 1981 fire. The two-storey house, with woodwork that exacts a second glance, was the home of at least five viceroys and served as the governor’s house since Independence. Then governor Amin ud-din Ahmad Khan lost all his personal artifacts in that fire. Raj Bhawan was shifted to Barnes’ Court, or Himachal Bhawan, and restoration of Peterhoff began. It took almost 10 years to complete the project. Peterhoff is now a luxury hotel of the Himachal Pradesh Tourism Development Corporation. On January 28, 2014, Shimla lost the 1904-built Gorton Castle, a grey stone building with wooden interiors on a hilltop. Minto Court, one of the last few iconic structures, joined the fire list in November 2014. Firefighters battled five hours to control the flames from spreading to the Viceregal Lodge next door. This two-storey wooden building was the office of Deepak Project, a wing of the Border Roads Organisation.

Gone with the Wind—the Melrose Compound in Nainital this December.

Cause and Effect

The house fires have transformed the way Shimla looks—the old architectural spaces, landmarks surrounded by dense cedars, oaks and deodars, are now filled with boxy concrete eyesores. These new houses are incompatible and have rapidly changed the unique character of the town. The British architects and engineers used wood extensively as the material was abundant locally and has high insulation properties. It’s natural and beautiful, but highly combustible too. These houses were built for specific purposes, the design meeting the requirements—bungalows for sahibs, hospitals for the military etc. The British were conscious of the safety features. All these got jumbled up after Independence. Like Snowdown hospital, now repurposed as Indira Gandhi Medical College. Modifications were done, but upkeep and care got compromised. Electrical wirings and fittings remained unchanged for years; ill-maintained as well. Most buildings don’t have fire alarms and sprinklers either. “Thus buildings after buildings are going down the hill, gutted in fires,” conversationist B.S. Malhans says.

In almost all cases, the culprit is a combo of short circuit and negligence. Prakesh Lohumi, a journalist who has reported many a Shimla fire, points to another cause: arson “to destroy records or cover up misappropriations in official records”. Author S.N. Joshi, a retired IAS officer, wonders why only government heritage buildings, barring the privately-owned Jankidas & Sons on Mall Road, caught/catches fire. “It exposes the inadequacy, lack of professionalism, negligence, and casual preparedness in dealing with fires. These are public property and nobody cares,” he says. It’s not hard to see that careless attitude. Of 450 fire hydrants in Shimla, 185 are out of order. Historian Raaja Bhasin, a convenor of INTACH, agrees that Shimla’s heritage has been lost to indifference, ignorance and negligence. “Overloaded circuits, bad wiring and heaters left unattended.” Shimla deputy commissioner Aditya Negi informs that advisories are issued to the offices and as a rule they are supposed to assign an employee to check all electric gadgets and heating appliances are switched off after the staff leave. Still, the fear of an inferno looms over the town after each sunset.

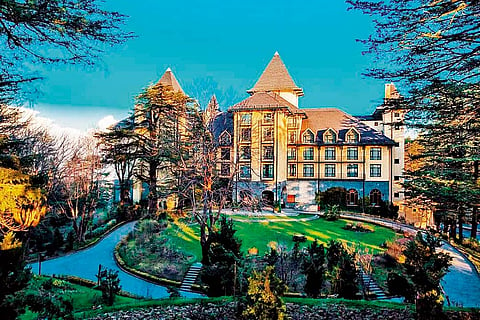

The Wildflower Hall Hotel near Shimla was restored after a fire in 1993.

Rise and Shrine

Up north in Kashmir, house fires have been burning down heritage as well as history. Flames of insurgency and counterinsurgency reduced the Sufi shrine of Charar-e-Sharif and about 200 adjacent buildings to a charred heap in May 1995. The army and Hizbul suffered fatalities, but the biggest casualty was the 15th century mausoleum of Sheikh Nooruddin Wali, Kashmir’s patron saint. When the Farooq Abdullah government drew up a reconstruction plan a year later, more shock awaited. There were no records to restore the shrine to its original form. An architect was sent to Samarkand to look for architectural resemblance. But Samarkand has brick architecture, while wood has remained the dominant feature of Kashmir for centuries. The shrine couldn’t be rebuilt exactly the way it was. Another case in point was Khanqah-e-Faizapanah in Tral—destroyed in early 2000 and couldn’t be restored in the old style as there was no documentation.

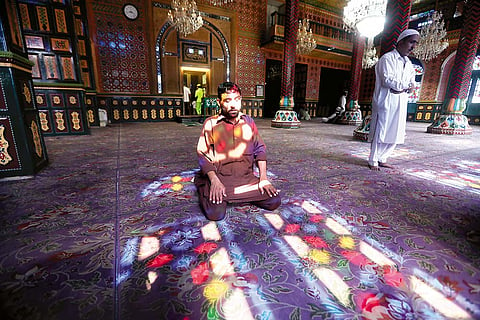

The Dastgeer Sahab in Srinagar burns on June 25, 2012; the rebuilt shrine’s exterior and interior

And so in 2005, INTACH was asked to document around 800 historically important structures, including heritage buildings. Minute details were videographed and designs were put on paper. This helped. A fire destroyed the shrine of the 11th century Sufi saint Sheikh Abdul Qadir Jeelani, popular as Dastgeer Sahab, in Srinagar. The wooden structure was an architectural marvel—the ceilings were made in an old Kashmiri-style woodwork called Khatamband, with papier mache panels painted blue, green and gold. Antique chandeliers, invaluable wood carvings completed the ensemble. All were lost, but not quite. A year later, on the night of November 14, lightning set ablaze the Khanqah-e-Moula shrine on the banks of the Jhelum in Srinagar’s old city. Built in 1395, the square wooden house, with a pyramid roof and extended balconies, had features of Buddhist, Hindu and Islamic architecture. It’s dedicated to Mir Syed Ali Hamdani, a Sufi master of Persian roots. Three more shrines are devoted to him—one in Ladakh and two in south Kashmir’s Anantnag and Tral districts. In November 2019, a fire burnt the shrine in Tral. Armed with digital data, INTACH rebuilt the Dastgeer Sahab shrine exactly like the original. And Khankha too.

“Most of the shrines and old buildings are made of Deodar. Deo means broad, Dar is wood. Deodar is called god’s timber. The wood withstands the vagaries of nature…weather, temperature. But it is oily and so, a fire hazard,” says Saleem Beg, convenor of INTACH, Jammu and Kashmir chapter. What’s left unsaid, perhaps for the insouciant poet to make virtue of, is the ability of a cedar, deodar or oak to warm a weary heart. All it needs is a fire retardant inside the head and by the family chest.

Tags