Initially, it’s a thick towel that she washes daytime, squatting in front of a granite slab in the leafy compound of the house the lady lives on rent with her husband. Two buckets—one metal and the other plastic—occupy to her right, while a coconut tree-trunk and a shack thatched out of its palm-leaves form the backdrop. A little boy appears from other side of the poles-tug fence; the homemaker calls him in—before sending him on a short errand, which he does successfully. He is then taken inside home and served a plate of rice and curry.

It’s a sight from Swayamvaram. There is nothing particular that takes the story forward in this short scene of the 1972 movie that triggered in a wave of neo-realism in Malayalam cinema.

Almost 45 years have passed since Adoor Gopalakrishnan released his debut film, making his mark as one of India’s top directors. The master craftsman has come out with a dozen feature productions thence, most of them have been hailed as classics.

Today, though, this inconsequential scene (of 3 minutes 40 seconds) seems to have got some unexpected focus—circumstantially. For, a state upcountry has taken offence to a college theatre group’s show, to the extent of disqualifying them on charges of “obscenity”. Why? Well, the on-stage performance used words such a “bra” and “panty” in the play. The capital’s Kamala Nehru College’s Lakshya’s Shahira Ke Naam bore words like ‘bra’ and ‘panty’ that apparently led to its disqualification from a theatre competition organised by Sahitya Kala Parishad, a culture wing of Delhi government.

The incident last week triggered debates about prudishness bordering on the absurd, even as the official word was that the play primarily carried cuss words that worked against it for the judges.

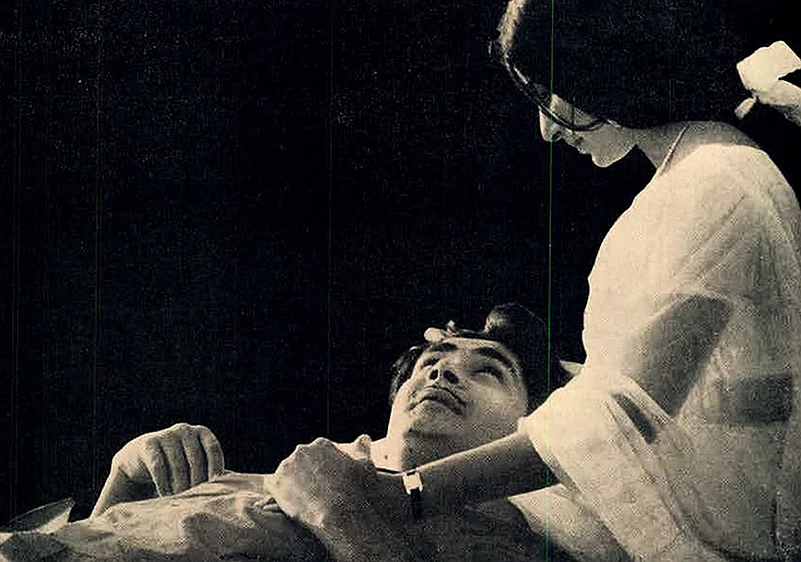

Adoor’s Swayamvaram, for the record, shows the struggles of a lower middle-class family where a new-married couple strives to make both ends meet in a city not near their native village. In the above-mentioned scene, the housewife (played by renowned Sarada), after keeping aside the water-soaked towel, is seen applying soap on a brassiere. She goes on to brush its cups, while tapping the garment on the slab—a routine act that is part of her household chore.

That is when she notices the little boy, having taken a pause with a bicycle rim that he was rolling. It’s a quiet entry, some 20 metres away from where she sits. His face subtly reveals his warmth, a near-suppressed eagerness to be friends with the new aunt next door.

Sita (the name of Sarada’s character) senses it, and beckons her. Overcoming initial dithering, he comes close to her. She learns his name is Sukumaran. Sita doesn’t wait to make her need clear: “Would you run to the store and get me a pack of indigo powder?”

The boy nods in agreement, and rushes to the shop—driving an imaginary car (or bus). By when he returns, the wife has spread her husband’s shirt on the clothesline. “Oh, you have been very quick,” she tells the boy in appreciation.

Sita puts the powder in the water even as she keeps talking trivia to Sukumaran—learning that he is a class-three student detained for a second year in school, where he has a funny story of mischief to his credit. Amid this, Sita has given her bra the bluish tinge, lifted it from the bucket and squeezed it for the water to drain.

It is when she asks Sukumaran about the teacher (Mary Miss) at school that Sita hangs her bra in the sunlight. By then, her face is close to the camera, which also means the undergarment is, practically, a slap on the face of the conservative viewer. The sprightly way she does the act amounts to a slap on unwritten squeamishness Malayalam cinema has practised all that while in its history starting 1907—even after Neelakuyil came up as a neo-realistic melodrama in 1954, portraying hard social realities.

Possibly, the ‘unsexiness’ in the ‘bra scene’ saved it from a cut almost half a century ago. The authorities, in hind sight, seem to be far wiser than those who judged Shahira Ke Naam in 2017.

Earlier in the Swayamvaram scene, Sita, while going inside to give Sukumaran the money for the indigo powder, mops the water in her hands with a mild press of the palms on her buttocks. That too—viewed with another angle—can be dubbed objectionable. But at least the Censor Board didn’t find it so.