Ramakaushalyan Ramakrishnan’s Poem of the Wind is made of fragments. We dip in and out of moments and scenes from a theatre artist Bharani’s life. These range from his childhood to the very nether. Increasingly, sadness of the unsaid accumulates. There’s so much he wants to say. He aches to fly off but is held back. His pain and grief materialise through a voiceover binding every chapter together. It’s wistful, impassioned and searching.

The film staves off any obligation to narrative structures. Instead, it swirls, freefalls and crashes through its ruptured episodes. There are no high points, rather a series of ebbs in the portrait of the artist that forms. Ramakrishnan, who has also shot the film alongside Sanjay Sreeni and Kishore Karthik, uses the camera with the languor of a drifter. We are let into snatches from the man’s past—a network of violence and coercion, which disorients his deeper impulses. Every flashing snippet presents the shape of his scars.

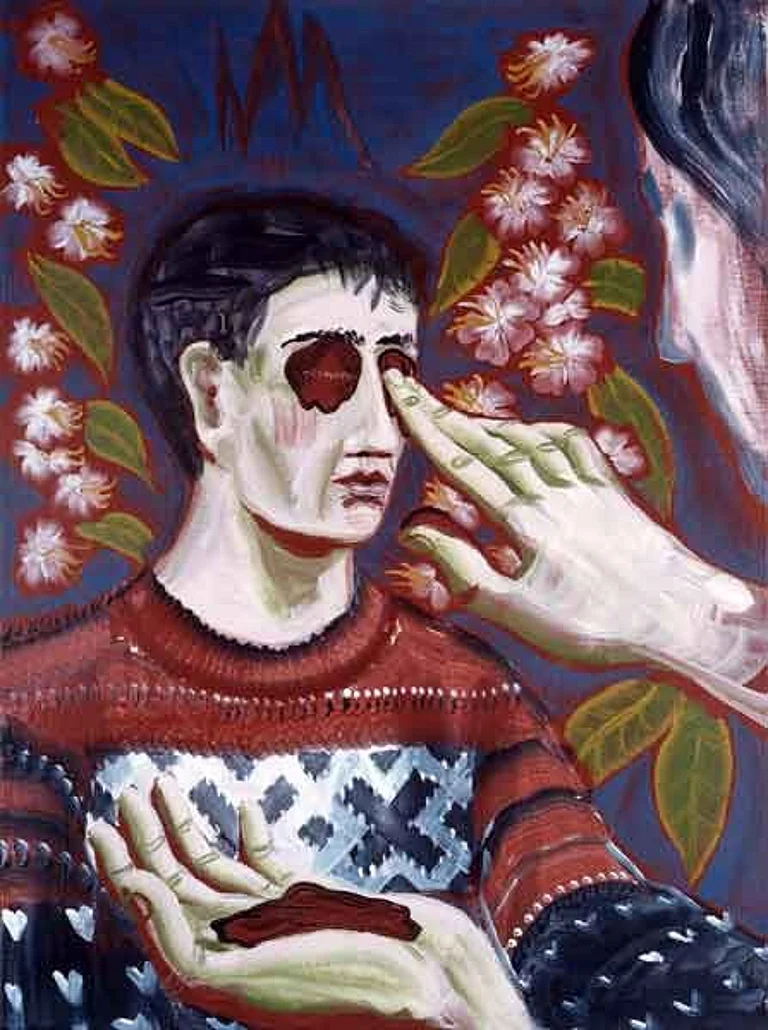

The meandering nature of Bharani’s reminiscences finds a contrast against the very rigidity of adherence he endures. There’s no straying from hardline norms—the social intruding on individual expression and identity. Bharani wrestles with projections of masculinity. As a child, he harbours conventional prejudices about gendered difference. It’s not that there aren’t pockets of resistance. In an early scene, his sister questions the act of perceiving women merely and wholly through the prism of beauty. She asserts recognising womanhood’s ferocity and valour. Bharani is quiet for a while before he retorts that women are unequipped for wartime. With a touch slow and sure, the film prises out the elemental push-pull in Bharani between inhabiting masculinity and moving outside it.

A deep unhappiness trails him. He has to re-negotiate a whole host of conflicts jostling within. He can’t find himself at ease within the configurations of heteronormative, aggressive masculinity. His life is a tussle between conditioning and the discomfort he experiences with it. It’s in the fleeting space of performance that he can express some of his anguish. However, the minute he is out of the space and back amongst men, the rush of connection he felt he elicited is negated. They jeer: who claps for plays on women? Bharani’s desolation intensifies furthermore. He’s dismissed and derided. A certain fluidity that performance allows him is put through its own trials. Can he own up to his self?

Melancholy and resignation wash over Poem of the Wind. Patriarchy exerts a vicious stranglehold of power; its rhetoric of superiority and violence edges out compassion and tenderness. The film also weaves in the contemporary socio-political fabric fraught with fundamentalism—communal tensions spark off in towns at the sites where plays are staged. But this segue doesn’t bristle as it should have. On the micro and intimate level, Poem of the Wind gathers tense undercurrents. Theatre is a conduit for tough, direct dialogue. Various anxieties are laid bare within the confrontation of a monologue. Isn’t empathy—that women are believed to have—a curse?

“If I’m soft as a flower, am I not man enough?” Bharani demands. This lamentation threads together the film. He yearns for release, liberation, acceptance. Innocence is lost; the blue bird of his childhood has disappeared. Instead, there’s the invasion of proud, emphatic, brute force masculinity. It’s an imposition that inevitably forces itself in. The film feels a tad unsure when Ramakrishnan accentuates the literal violence and abuse on women’s bodies on a sidetrack. It’s more effective in the dread-coiled wait, though the sepia tone is amateurish and distracting. Some of the visual shifts don’t land as smoothly as others. Nonetheless, Ramakrishnan evocatively builds an inner world that’s under constant threat.

Poem of the Wind culminates in ruins. All that surrounds Bharani is the wreck of a society unable to reflect on its damage. Everything has fallen apart. What remains of him is just a faded residue.

Poem of the Wind had its World Premiere at the Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF) 2024.