“What art lost, theatre gained.” This is the epigrammatic manner in which I first heard, as a teenager, of Ebrahim Alkazi’s paintings and drawings. The assessment came from my mentor, the poet and art critic Nissim Ezekiel, one of Alkazi’s closest friends from the late 1940s to the mid-1960s. The two men remained in touch, although one would migrate to Delhi and transform the National School of Drama into a powerhouse of creativity in theatre, while the other would anchor himself in Mumbai and sustain a vibrant ethos for poetry around the PEN All-India Centre.

To most people, Alkazi—who turned 94 on October 18—is a foundational figure of postcolonial Indian theatre, a mentor to several generations of actors on stage and screen. The art world knows him as a champion of Indian modernism. A serial institution-builder, he founded, co-founded or transfigured the Theatre Group, the Theatre Unit, the National School of Drama, Art Heritage, Sepia International, and the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts. These achievements have, however, eclipsed the fact that Alkazi was a visual artist in his own right. Visitor after visitor to Opening Lines, the exhibition of his works from 1948 to 1971, which I have curated at Art Heritage and the Shridharani Gallery, New Delhi, has much the same look of amazement and the same response: “I had no idea he was a painter.”

Self-portrait, acrylic on canvas

Talking to me about Alkazi’s art on that afternoon in the late ’80s, Ezekiel evoked the years that he and Alkazi had spent in post-World War II London, a metropolis partially in ruin, yet seized by a resurgent energy after six years of conflict. Together with Alkazi’s wife Roshen, the painter F.N. Souza, and Souza’s wife Maria, they would attend concerts and lectures, visit museums and galleries, go into the countryside. All around them, painters, theatre-makers, dancers, musicians, and film-makers were gearing up for a renaissance. Alkazi’s ‘basement flat’ in Lansdowne Crescent, Notting Hill—residence, studio, meeting place for the group—makes its appearance in several of Ezekiel’s poems.

And yet, for over three decades, Alkazi’s paintings were a Holy Grail, never seen by mortal eye. Until about two years ago, when I received an excited call from theatre director Amal Allana, Alkazi’s daughter. Swearing me to secrecy, she told me what she had discovered during a spring-cleaning mission at the family farmhouse. From an old trunk, there surfaced a battered folder bearing the label of the SS Stratheden, the P&O Line ship on which Alkazi had made his voyage out to England in 1948 and back in 1951. Inside, largely pristine and untouched by the dread hand of time, were the works he had exhibited at the Left-leaning Asian Institute in London in 1950 and in Mumbai’s newly opened Jehangir Art Gallery in 1952. Amal invited me to curate an exhibition around this marvellous discovery. As we went along, she also re-discovered the ink and charcoal drawings that her father had exhibited at the Shridharani Gallery in 1965. It has been a very special privilege for me to revisit these works and their ambient histories, and to present them to a contemporary audience.

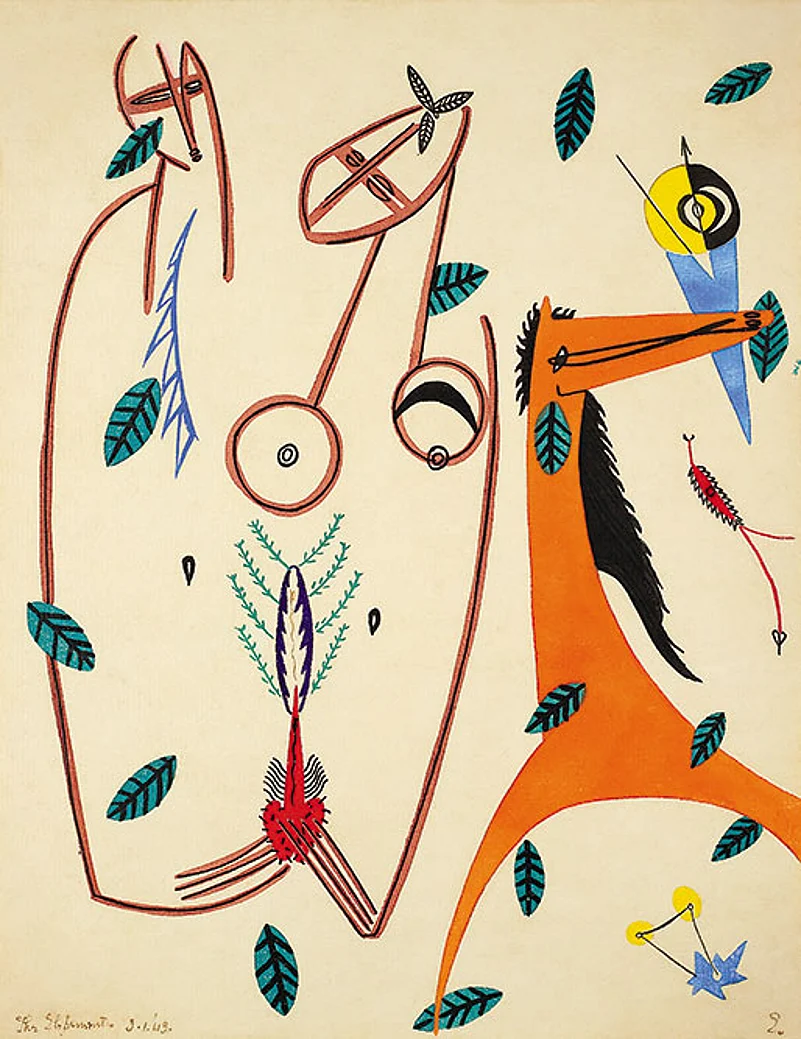

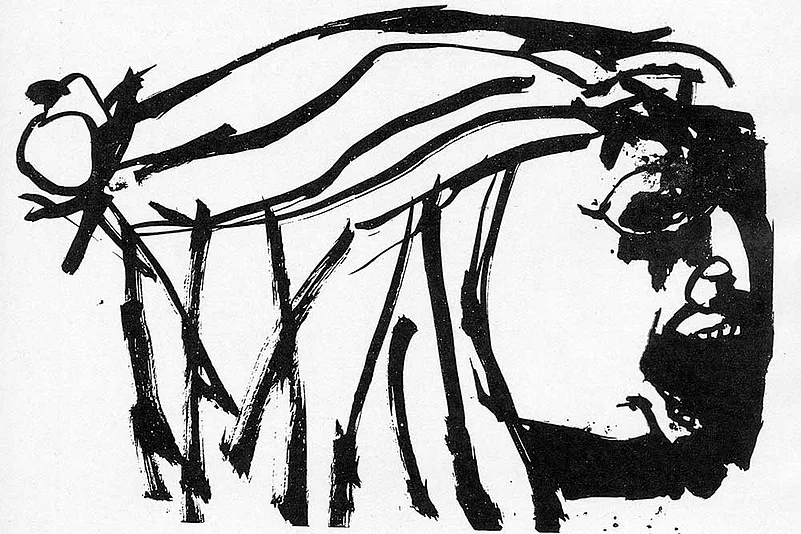

Elopement, mixed media

What strikes us most forcefully is how formally accomplished these works are, how robustly they stand up to the passage of time and shifts in taste. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, while still in his twenties, Alkazi drew critically and productively on the then-dominant global artistic preoccupations with Primitivism, myth, and anthropology. Stone Age drawings, West African masks, Mesoamerican sculpture—all these infuse his early work with their energies. While we now regard Primitivism as the articulation of an acquisitive, colonial mentality, it did hold out the promise of transcending the conventional limits of Western art-making during the mid-20th century. How, we may speculate, did a young and already polymathic intelligence like Alkazi’s, drawing on his Arab and his Indian inheritance, embrace and adapt it?

Reclining Christ, mixed media

Alkazi has sometimes referred to himself as a ‘Maharashtrian Arab’. The self-description is accurate: he was born in Pune in 1925. His father, Hamed ibn Ali al-Qadi—the family name was rapidly Anglicised to ‘Alkazi’—had come to India as a spice merchant in 1915 from the al-Qassim region in the heart of Nejd in the Arabian Peninsula (Nejd has, since 1932, been part of Saudi Arabia). Alkazi’s mother, Miriam, belonged to a Kuwaiti family with strong links to western India; she spoke Arabic, English, Marathi, Gujarati, as well as Urdu. The family’s mental world was multilingual and transcultural. A resident tutor, a young Arab, instructed Alkazi and his siblings in Arabic and magazines were ordered from Egypt. They were also in close social contact with their Parsi, Anglo-Indian and Maharashtrian neighbours on Synagogue Street. V.N. Dixit, who founded the International Book Service, Poona, in 1931, would welcome Alkazi, even as a 13-year-old boy, to his bookstore; Alkazi’s lifelong habit of collecting books began early. Artistically attuned, three of the siblings would go on to be artists: Alkazi himself, his older brother Basil and his younger sister Munira.

Alkazi’s work in the late 1940s and early 1950s is informed by his fascination with Shakespeare’s indecisive anti-hero, Hamlet; with Joyce’s picaresque reinterpretation of Homeric myth in Ulysses; and with the Christ theme, which had taken possession of his imagination as he transited through two Jesuit institutions, St. Vincent’s School in Pune and St. Xavier’s College in Mumbai. A key role in Alkazi’s trajectory must be assigned to his first mentor, the charismatic Sultan ‘Bobby’ Padamsee. Bobby, who had returned home to Bombay from Oxford in the early ’40s, was the scion of an Ismaili Khoja business family.

Medea by M.F. Husain, from Euripides’s Medea dir. by Alkazi

Like many of Bombay’s mercantile elite families during this period, the Padamsees were in transit between a more conservative culture embedded in a Gujarati-speaking ethos and a more cosmopolitan culture sustained by exposure to the Anglophone ascendancy. Bobby was a classic product of this transition: Oxonian and urbane, yet deeply interested in the aesthetic philosophies of the East, he wrote poetry, painted, and directed plays. He was responsive to a spectrum of cultural idioms ranging from Central European expressionism to southern India’s classical dance-theatre forms. He established himself as an impresario, directing cultural activity at St. Xavier’s College, which Alkazi had joined in 1942.

Coming under Bobby’s sway, Alkazi opened himself to a thorough-going internationalism, while also being carried along on the momentum of an India on the verge of gaining independence. In this, he clearly also followed his own instincts as a transcultural subject: he came from an Arab family that had settled in western India. Bobby’s early death in 1946 devastated his family and friends, and inspired them to continue his legacy through what became, for many of them, a lifelong commitment to the arts. Alkazi had already fallen in love with Bobby’s sister, Roshen; they were married later in 1946. Their marriage was also a dynamic collaboration, as Roshen designed the costumes for Alkazi’s productions, and went on to immerse herself in research, writing the benchmark book, Ancient Indian Costume (1983).

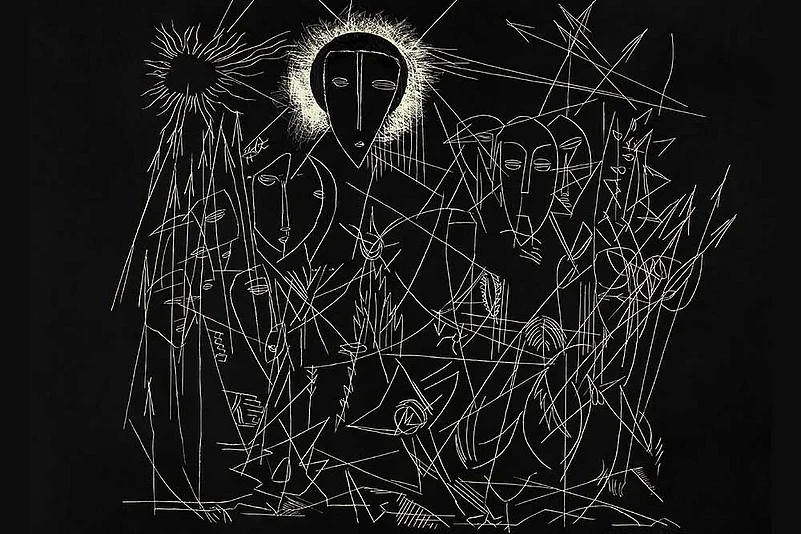

Last Night Did Christ-the-Sun Rise From The Dark, drawing on scrape board

Alkazi was only 36 when Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, one of Nehruvian India’s most magisterial cultural activists and institution-builders, invited him to head the nascent National School of Drama. Giving up his circle of colleagues in Mumbai theatre, he moved to the capital and embarked on a new phase of his life and work. The rocky massifs in the drawings that he exhibited in Delhi when he was 39 evoke Purana Qila and Feroze Shah Kotla, historic sites where the artist, in his role as theatre-maker, staged his grand productions of Dharamvir Bharti’s post-apocalyptic verse play, Andha Yug, and Girish Karnad’s political allegory, Tughlaq, during these years. To this early-1960s body of work belong, also, landscapes that double as seascapes, gravid nudes that rejected the coyness of the objectified female body, still life arrangements infused with the mystery of a sacred rite.

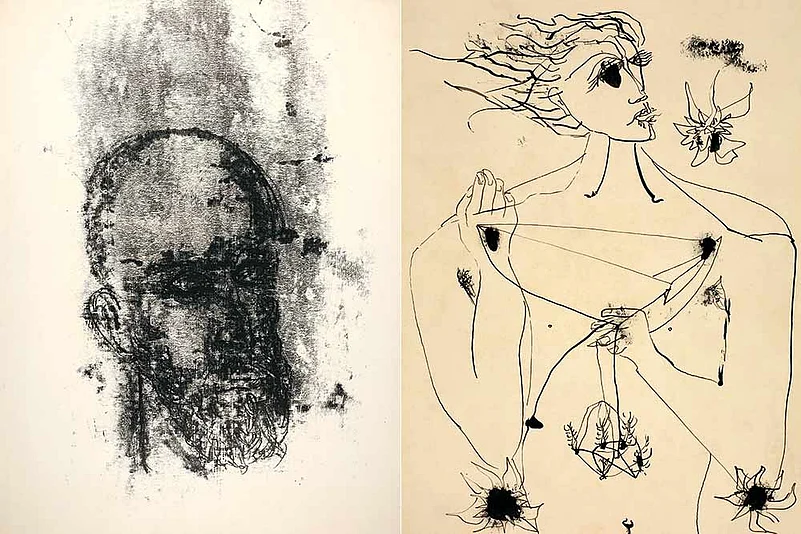

Left, Head 1, mixed media on paper; right, Soliloquy, Hamlet II, pen and ink on paper

Of all re-discoveries, it is the prodigy who renounced his early path who most compels our attention. Viewing these works many decades after they were produced, we marvel at their intellectual confidence and artistic ambition. This is not the usual ‘promising’ work of a beginner or a dilettante. On the contrary, we are offered evidence of the mature, evolving vision of an artist in advance of his peers. Alkazi’s art takes its place in that larger drama of anti-colonial self-assertion by which artists and intellectuals from the former colonial peripheries assumed their proper place in the world, speaking from emergent centres, even ‘off-centres’, in the memorably defiant definition applied by the Nigerian-American curator Okwui Enwezor. What turn might Indian art have taken, had Alkazi continued actively as a painter? What fresh stimuli or startling breakthroughs might he have proposed? How might his continuing experiments have challenged his confreres to keep up?

(The author is a poet, art critic and curator. Opening Lines: Ebrahim Alkazi, Works 1948-1971)