Tradition and technology have always shared a tenuous relationship. The latter has been seen by tradition as some sort of a usurper and corrupter. Though the usual cliches of tradition being a movement, a non-static flow of culture, are universally bandied about by the intelligentsia, the truth remains that in our heart of hearts all of us attach an untainted oldness to tradition and place it on a golden throne.

Tradition gives us value, history, antiquity and lineage, all of which are needed for us to feel pride in our ancestors and ourselves. To further this, in every community and within its microcosms, traditions go through a mystical sieve that decides which tradition needs validation and which one is to be forgotten. And don’t be so sure that the erased will remain that way, because there may be a time in the future when it will be brought back to life to serve another, as yet unsuspected, purpose.

The word technology is so unmistakably seen as a creation of modernity that it is hard to realise that this tool has existed from time immemorial, from the invention of the spade up to today’s touchscreens. Though we know this, our sense of the ‘techie’ is very different. It is seen as a post-industrial revolution feature and more recently inextricably connected with the electronic-digital world. And hence, technology, though a partner in tradition, always seems to want to upgrade tradition, teach it a thing or two about how things are to be done in this day and age. If we place these two words in an imaginary timeline, tradition will be a dateless past while the techno an undated future.

As you can see, understanding has very little to do with how we feel about these terms and that is the crux of the issue. Because the moment a word is used or its real referents paraded before us, we respond and that response is emotional, instinctive, and remains the basis on which we will embrace or reject it. Of course, many a time, the word reluctant has to be prefixed to the embrace or rejection.

When we bring technology and tradition into the sphere of music, the complexities only multiply. Musical values are placed on forms using these terms and their socio-political meanings.

We have to first enquire how tradition absorbs technology, leaving it bereft of an independent identity. Every musical instrument is a creation of the scientific temper, an enabling tool that gives music numerous dimensions and tones. In fact, a musical instrument can add to the aesthetic possibilities of a musical form. In my own genre, Karnatik music, the veena, nagaswaram and the foreign violin and electric mandolin (it is actually a mini-electric guitar) have enriched its shape. But there is something else, something fundamental, about these adaptations. They have come from a deep understanding of the aesthetic foundations that give the music its soul, sound and character. And this collapses the dichotomy between tradition and technology. Continuity was felt even if the tones were new and the expression was avant garde. Even the basic sruti box—a drone instrument that uses bellows, much like the harmonium—was replaced by the electronic sruti box and now by iPad applications. The original wooden tambura (tanpura) has also been replaced by iPad applications. While there is no denying that the raw acoustic sound of the tambura is unique and requires a different kind of listening, the fact remains that the traditional form has unequivocally accepted these changes as part of the tradition itself.

But another possibility hovers. What happens if newer technologies are adapted without the adequate understanding of the form, or as a tool with its own wayward, directionless propensities? Disruptions can be of two kinds: those that shake up a system from aesthetic slumber while holding hands with its core intention and others that only look for contrarianism. Interestingly, the whimsical contrarians enter the musical universe and inexplicably get acceptance in spite of the fact that they destroy the basic character of the music. In their present form, the saxophone and keyboard are such intrusions. How is it that tradition accepts these changes even when they mess with DNA of the music? These movements reveal to us a crucial facet of how some technologies receive easy acceptance.

What is truly held sacrosanct even in music is not the idea of the aesthetic-musical form, it is the underpinning socio-political-ritualistic and possibly religious foundation that carries the art form. The purists within may whine and complain, but we tend to accept technologies that damage musical form with alarming ease. But if technologies shook the social edifice of the art, then I am certain there would be a collective hue and cry. This is as true of the classical, as it is of art forms practised among marginalised communities. While many of the technical tools of the music and themes have changed, the socio-political character more or less remains the same. And those who are swimming against this tide are fighting a hard battle.

A.R. Rahman performing at the opening night of the Jai Ho concert in New York

The cinema world presents another facet to the relationship. The most beautiful aspect of cinema music is that it can never have a singular aesthetic form even if its intent remains the same. This is its greatest asset. It responds to story, time and context and the music is reflective of that requirement. Therefore, its nature is to be musically open and this allows for a free flow of musical ideas not bound by any specific aesthetic identity. The aesthetic identity is defined in every movie specifically by the needs of the story that is being told. Technology in cinema music is part of the sound that is needed and has always been the first place in India where many audio-related tools have found their home. This comfort with technology is a result of a formless form that music in cinema embodies. But this has come with its own set of serious issues. This liquidity has at times manifested itself in aural insensitivity. The arrival of the computer and sound processers has affected many instrumentalists of the film world. Except for the specialist superstar instrumentalists who are called in for cameo roles, every other orchestration is system-generated. This has certainly created a serious livelihood issue for many. But there is something more to think about. Is there a difference between a sound sample-generated tabla and an actual tabla accompaniment to a song? The answer is a resounding yes, but most of us are not capable of spotting the difference. When we are incapable of that level of sensitivity, does the music director then choose between the two purely on the basis of economics? It is after all cheaper to program a computer than pay an artist. What then also happens to the most intangible aspect of experience, the perfection that is derived from the inner emotional being and not in programmable sameness. Today, we may have reached a point where film music composing itself has been redefined to mean music selection and arranging from choices provided by pre-programmed computers. That invisible line that separates creativity and enabling tools needs to be understood soon, otherwise, we may very soon surrender artistic intellection to artificial intelligence.

Then there is a whole world of music that seems to depend on the electronic-digital sound. For the highbrow, this is not music, just a mixture of sounds they may even call noise. The young think it is hip and cool. Without falling into this trap, let me ask a different question. Existing popular forms of music have an expanded texture with the use of electronic and digital sounds, but has a new aesthetic form evolved out of these electronic sounds beyond attractive titles like EDM? Unfortunately many of these come and go as phases, only to be replaced by another technological tool. Maybe this says more about the intention behind these technologies rather than the technologies themselves.

Now that I am talking about the intentionality, we need to address technology’s perceived role as a democratiser. I have heard it said many times that the microphone and radio democratised classical music. On the face of it, this seems logical, but let us dig a little deeper into the issue. The use of the microphone has admittedly had a great effect on every musical form. From the voice to the nature of listening, everything has changed. There is no doubt that at a fundamental level the microphone allows for the music to reach a larger number of people and therefore music, or for that matter any performing art form, must have benefited from this outreach. It is also true that those who may have previously never heard or had access to an art form can now enjoy it. But if it was so simple, most art forms must today have a diverse audience comprising of people from different sections of society. We know this is not true.

Though airwaves are unbound, the social weave of each of the performing art forms is taut. Technology does not question fundamental social issues that keep people away or within socio-artistic boundaries. I have heard that there were times when rikshawalas used to listen to the great Karnatik musician Madurai Mani Iyer when he performed at the Kapalishwarar temple in Madras. There is no doubt that the loudspeakers carried the music to them, but the really enabling force was the practice of art on the grounds of the temple. When that was in place, access became a possibility, even though it was from a distance, and technology became a well-used tool. But without that intention the microphone does nothing. In the case of the radio, it is only those who know about a form of music and are aware of when to switch the radio on who listen. Cinema music is the most popular on radio channels simply because the form demands and captures the mass psyche of any society and the music benefits from that attention. In the case of marginalised art forms, technology seems to provide access to newer markets, but some other complications arise. The cinematic platform provides opportunities for some art forms but always on its own terms. Therefore, while Gana music (an art form practised among Dalits in Madras) has found place in cinema, it has been reduced to lewd ‘item number’ songs. This has created a lot of tension in the art and its practice.

The notion that technology is a non-discriminative mechanism is untrue. Irrespective of the colour, caste, gender of the singer, the mike behaves the same way and the receiver will also hear without any judgement made by the mike. But it is human beings who decide who has access to the mike, who stands in front of it and it is we who must make the music available in spaces which allows for it to reach people of diverse cultures and in turn enrich the art. Technology just by its mere invention can never remove the historical, social and emotional boundaries that keep many art forms closeted. Neither can it check the rampant commodification of art forms.

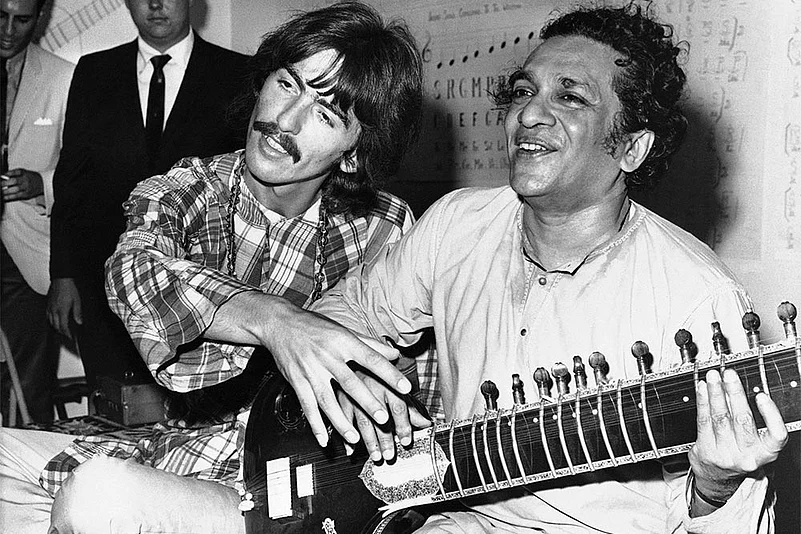

Even in this internet-driven age, we find art forms bundled in their own cocoons. The musically-tuned reader may ask: what about collaborations and the intermingling of sounds from across the world? The internet has made it possible for any one to share and hear music from all corners of the world with ease. But I have to wonder if this has resulted in newer aesthetic dimensions being added to the arts. In fact, some of the most profound jugalbandis between different music cultures have taken place offline. I will also say: students of art who have not as yet mastered any one form of music are often musically in a state of bewilderment when they bombard themselves with too many impulses. And once again, we cannot blame technology, it is about our own understanding of learning that needs to be questioned.

Democracy in art is both an internal and external query. It is built on structures that define the nature of the aesthetic form. It is as much an aesthetic need as it is a socio-political necessity. Democracy in musical sound is a result of immense clarity in the inhabiting musician and listener. This implies that all those barricades in our minds and those we impose on the system in order to maintain control and keep others away must be broken down. Tradition and technology live a common life—as instruments of control. And if the manipulator is not questioned the music will remain stilted, morphed and societies built around it limiting. The ethics of living must guide us in the creation and use of technology. It is not just about making things simpler or convenient, it is as much about creating beauty that can be shared without disparity. It is ultimately the coming together of people, a constant process of self-questioning and an urge to learn and share that creates beauty in and around music.

(T.M. Krishna is a Karnatic vocalist and author of A Southern Music: The Karnatik Story, public speaker and writer on human choices, dilemmas and concerns.)