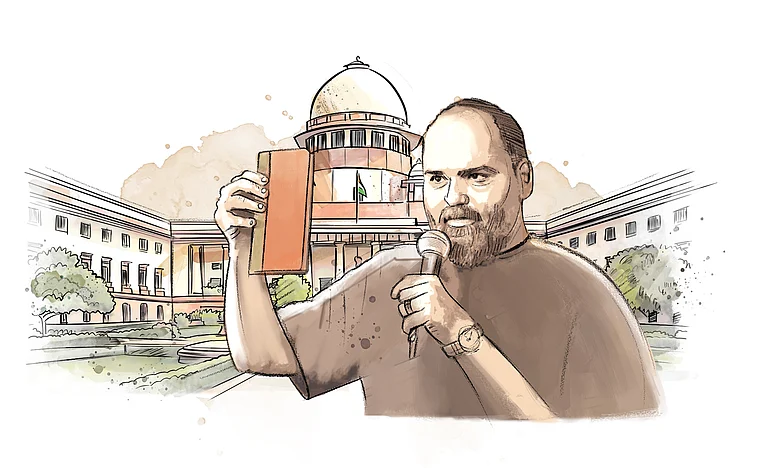

The journey of the All Living Things Environmental Film Festival (ALT EFF) began in the picturesque hill station, Panchgani in 2020. With an aim to drive awareness around environmental issues, Kunal Khanna—director and co-founder of ALT EFF—along with his team, launched it virtually in 2020 due to Covid and did the same in 2021. Since 2022, there have been on-ground screenings of films in various cities. The main aim of this festival is to have a conversation about pertinent subjects such as nature, environment, and climate change. ALT EFF is now in its 5th year with a great jury. Actress and activist, Dia Mirza is helming the jury and director Richie Mehta has been roped in as an ambassador of the festival. It kickstarts on November 22 in Mumbai and continues until December 8. Around 72 films will be screened in different parts of the country and also internationally.

Ahead of the festival, Outlook India had a freewheeling conversation with Kunal Khanna, where he spoke at length on how the idea of the festival germinated, and its role in creating awareness among citizens. He also gave recommendations to look out for this year’s edition. Excerpts from the interview.

How did this festival come into being?

Cinema has an amazing potential to evoke an emotional impact and is an engaging medium to draw people's attention and make them feel connected to issues. It’s also a personal story for me, because I lived in Australia for about 13 years, and I'm a trained economist. After finishing my undergraduate studies in 2007, I worked in economic policy for four-five years for the Australian government down there. During this period, I volunteered at film festivals, like the Environmental Film Festival in Australia, the Transition Film Festival, the Human Rights Film Festival, and also in a range of other arts-related organisations.

The experiences at these festivals helped shape my thought process and gave me a deeper insight into issues that I really cared about. But I didn't have enough information on or didn't have a real deep or nuanced understanding of such things. So, I decided to take up a new environmental degree and then continued working as an environmental consultant. When I came back to India in 2018, I became aware of the ecological crisis and its intricacies. There was nearly no understanding of that both in my own community and among the people I was interacting with. The very first step for anyone to make a change or move towards any action is to become aware of what the issue is. And I don't think there's a better option than film to create that widespread awareness.

How does this kind of festival help create awareness among citizens? Do you feel ALT EFF has succeeded in doing so?

We conduct a lot of extensive surveying and anecdotal evidence around how people are interacting at events, screenings and the festivals we're hosting. After that, we ask these questions such as: Has attending ALT EFF or learning about this issue or watching these films made you change your behaviour or brought a shift in the way you go about your day-to-day lives? And we have received an overwhelming affirmative response from people. So, that's one way in which we're able to track the impact we're making.

There's a film this year called Stubble – The Farmer's Bane. This film is so timely because it interrogates the issue at a deeper level. If you ask anybody on the street why there is so much pollution, the first answer is going to be stubble burning by the farmers. That's been the mainstream narrative and that's what the media is telling us. This film provides a nuanced understanding of why it is happening and what are the policies, the priorities. It highlights the cycle that farmers are stuck in, because of which they are compelled to burn stubbles.

It also shows what the actual solution is and what kind of approaches can be taken. Which organisations work on-ground to change this? It gives us a bit of hope and also a clear direction.

Which issues is ALT EFF addressing this year? On what basis do you curate or select these films?

The 72 films in our programme touch upon everything from conservation of the natural world, to the impacts of uranium mining, to stories like the future of kelp as a major solution for carbon absorption from the air and its commercially lucrativeness.

The films get selected based on five criteria—striking a balance between the filmmaking and storytelling as well as the technical aspects of the films.

We find the best environmental films that have come out in the last 16 or 18 months. We got 400 this year, out of which we curated 72. Then we broke this programme down into certain themes, based on their contemporary relevance.

There are nine different themes in the festival this year- ranging from woman-led narratives to popular resistance and activism to the cost of growth.

How do film enthusiasts pursue funding for such endeavours?

From a festival perspective, we get our resources from philanthropists and organizations that prioritise environmental communication and are interested in environmental issues. We also get sponsorships from companies that are also working on environmental issues. Both sponsorships and philanthropy help us run ALT EFF.

I would say that in 2020-2021, environmental filmmaking was still nascent in India. But today it has matured a little bit. We've had amazing environmental films that have won the Oscars like The Elephant Whisperers (2022). All That Breathes—which went to the Oscars but didn't win, unfortunately—was also showcased and premiered at our fest. These Indian films are significant not only because they went to the Oscars, but because they happen to be environmental Indian films that are getting this amazing exposure and recognition. So where does the money come from for these films? They have to work really hard to raise these sponsorships or raise the production money. A lot of these resources come from overseas. National Geographic, for example, funds a lot of films. There is a range of international funds that provides resources for filmmakers. Also, some labs are emerging within India itself to specifically support environmental filmmaking. ALT EFF, too, is looking to launch a film fund or support the current existing funds for environmental filmmaking; but it all depends on the kind of sponsorships we can access to enable that.

Cinema is such a powerful medium to create widespread awareness but we don’t see more films on the environment or climate in mainstream cinema. What’s your opinion on this?

I would disagree a little bit with that statement because we are starting to see more and more of these films coming out in mainstream cinema. For example, Poacher, a series by Richie Mehta, was very much an environmental story. There's Sherni, which came out a few years ago by Amit Masurkar, and another series from Odisha, The Jengaburu Curse, which was very much around the issue of mining and human rights, touching on the environmental issue.

The range of other documentary-style films that are coming out on OTT platforms is very much on the environmental ground. So obviously, it's not going to be as big as a Bollywood production or have a big theatrical release, but it is continuing to come forth. I can assure you that there's going to be a lot more that will come.

Storytellers and filmmakers are sharing or telling our lived experiences—the abnormal rainfall for a farmer, sea level rise, biodiversity loss, loss of habitat, etc. All of these things will start to become part of mainstream cinema because that is now becoming a crucial part of our own lives.

How do you see the future of environmental documentaries or films in India? Is it bright?

It's very bright. We're getting larger and larger audiences at our screenings that want to engage and watch these films. The response to that would be more filmmakers telling these stories. There’s a lot of interest both here and internationally.

What are some of your top picks from this edition of ALT EFF?

From the Indian film’s perspective, there's a film called Saving the Bone- Swallower—a documentary film from Assam about this amazing woman who has single-handedly made a big conservation effort for this particular endangered species of bird called the Greater Adjutant Stork. There is a film called Requiem for a Whale, which happens to be an Israeli film. But it's also a really interesting film because it shows the apathy that we have today for the natural world. The story is about a whale that washes up on the beach somewhere in the Middle East. It’s a really lovely film.

Searching for Amani is one of my favourites, which is a film based in Kenya. It's about a ranger who gets shot in the line of duty and then it's his son going around to investigate and understand the different conflicts that are happening in that area. It's between the people who are traditionally land graziers and these external, international people who have come and bought thousands of acres of land for conservation. So, they happen to have more access to water and resources. There's this conflict between the locals and this conservation area. So it's again, a very complex situation and the way the film showcases it from the eye of the son is absolutely beautiful.

My Mercury is a really superb and unique conservation story as well. Junkie is a short film about e-waste, and it's based in Kolkata. It shows us the other side of our consumption of technology.