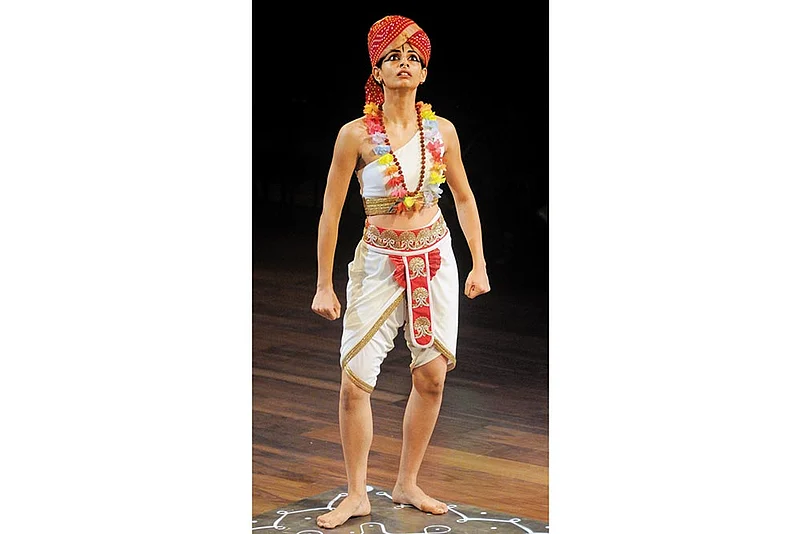

Shikhandi

Langauges: Marathi, english, hindi

Starring: Meher Acharia-Dar, Mahnaz Damania, Vikrant Dhote, Karan Desai, Nikhil Murali, Srishti Srivastava. Writer-Director: Faezeh Jalali

Rating: ****

Those familiar with the Mahabharata in any of its forms will know that there are no easy answers to the questions raised by the multitude of characters in the innumerable sub-plots mapping the epic. A swarm of ideas is also in battle at Kurukshetra.

One character through whom the epic raises difficult questions around gender is Shikhandi, a girl born to King Drupad (father of Draupadi too), who raises her as a boy, teaches her martial skills, even gets her married to another girl. Shikhandi grows up feeling traumatised and confused and even tries to kill herself for not having a penis. She then gets ‘manhood’ on loan from a Yaksha. However, on the battlefield—by which time she is both a man and a woman or neither—she confronts the invincible Bhishma, who drops his weapon as he won’t fight a woman. That changes the course of the war.

But that story is from thousands of years ago. Here in Mumbai, at the Experimental Theatre of NCPA, when Faezeh Jalali presents Shikhandi: The story of In-Betweens—written and directed by her and researched and mulled over for almost a decade (she first created it as a 20-minute, one-woman show in Berlin)—the story becomes a brisk, pinching satire about punishing times, then and now. The play, produced by Jalali’s company FATS The Arts and NCPA, is back in Mumbai after travelling to different Indian cities.

The 90-minute, no-intermission play starts on a high note and takes the audience on a fast-paced ride, starting with the battle scene of the Mahabharata. Jalali ambitiously blends Koodiyattam, Kalaripayattu, Yakshagana, aerial rope skills and English verse to create a modern retelling of the myth of Shikhandi, while still keeping it rooted. The actors don’t let her down—their energy and timing for dance, dialogues and diction in Marathi, Hindi and English lift the play several notches higher. Concepts of gender and sexuality are discussed and stereotypes shredded at every juncture, giving LGBTQ issues a strikingly ancient context.

Complicated sub-plots and back stories are explained rapidly in flashbacks and fast movements, continuously interjected with a modern, liberal take. The story of Shikhandi’s past life is a vivid example. Amba (Shikhandi in her past life) is kidnapped by Bhishma along with her sisters to be married to his brother. Amba has a lover and refuses to marry, begging Bhishma to let her go. But she is rejected by her lover, because she has been touched by another man—Bhishma. She can’t get married to Bhishma either, because he has vowed celibacy. Even as she weeps, there’s a quick aside about whether marriage is the only goal for a woman. The scenes with Lord Shiva, as he descends from the ceiling, are entertaining and effective. Draupadi too has a delicious part—a feisty girl who would do anything to get rid of dance classes and fights boys who bully Shikhandi.

For the team, after getting a teacher to teach Koodiyattam to the cast and travelling to Udipi to learn Yakshagana and rehearsing for several months, there were challenges galore. “You don’t get space to rehearse at the performance venue. So we realised that we need to move faster in smaller spaces. Knowing timing and the rhythm in the space where we are rehearsing as opposed to where we are performing is a challenge. Luckily at the NCPA, we got to do tech rehearsals and we also got five show runs, which was great,” says Jalali, who recently won a META award for supporting acting in the play I don’t like it as you like it. “Also, because it is such an intensely physical form, there are worries about injuries and the fitness of actors. But one remembers the ups.”

The strength of the play is in posing logical questions as if there was no baggage of mythology and religion attached to it, but without ridiculing or over-simplifying and glossing over details. This play is very different from the soul-stirring, existential quest of Peter Brooks’ Mahabharata (a 1985 landmark play to which a comparison for any play in this domain is inevitable), but it stresses more on the natural rights of human beings to be what they are and how the assertion comes in direct conflict with societal rules; a more relevant telling of the tale for our times. Not to mention the potential of the Mahabharata in drawing writers and directors to explore, unravel and discover the complexities of human life for a long time to come.