Mera jahaan kuch aisa ho jismein

Kaam ek majboori na ho

Jahan bazaaron mei ek tole par kaudiyan na milti ho

Jo mujhe bachchon ki cheekhon ke beech

Purane chulhe se joojhte

In band chaar diwaron mei karna pade

—Mera Jahaan Kaisa Ho? By Fatima Juned

A dreamy constellation suspended in the air catches your eye when you enter the hall. As you draw closer, you realise that it is an exquisite white dupatta with intricate muqaish work woven through its threads. Muqaish, a metal embroidery work which was brought to India by the Mughals, was once a trademark of Awadh. Today, while the modern day Uttar Pradesh—especially the Nawabi city of Lucknow—is popular for the chikankari embroidery work, muqaish has become a lost art. Fatima Juned’s photo exhibition Taaro’n Ke Darmeyan is an ode: not just to this fast disappearing art, but also its invisible women artisans.

The exhibition is part of a larger series of artistic endeavours that constitute the ‘G-Fest’—an ongoing event at Museo Camera in Gurugram, organised by reFrame, an initiative that mentors budding artists and produces as well as exhibits their works across the country. Artwork and photo exhibitions, film screenings and live performances by several artists are part of this unique event, which explores pertinent questions on gender through art.

Juned’s photo series is premised on the intersectionality of gender, labour and art. Her work illuminates the lives of women muqaish artisans of Lucknow, unacknowledged for their labour both at home and as artisans. “Auratein to ye kaam shauqiya taur pe karti hain,” (women do this work as a leisurely pursuit) she was told, when she first started interviewing male muqaish artisans for her project. “What really stayed with me was that these women—juggling household work, embroidery, purdah and childcare—are completely invisibilised and their labour is simply passed off as their ‘duty’,” she says. It was this realisation that took the shape of her photo series.

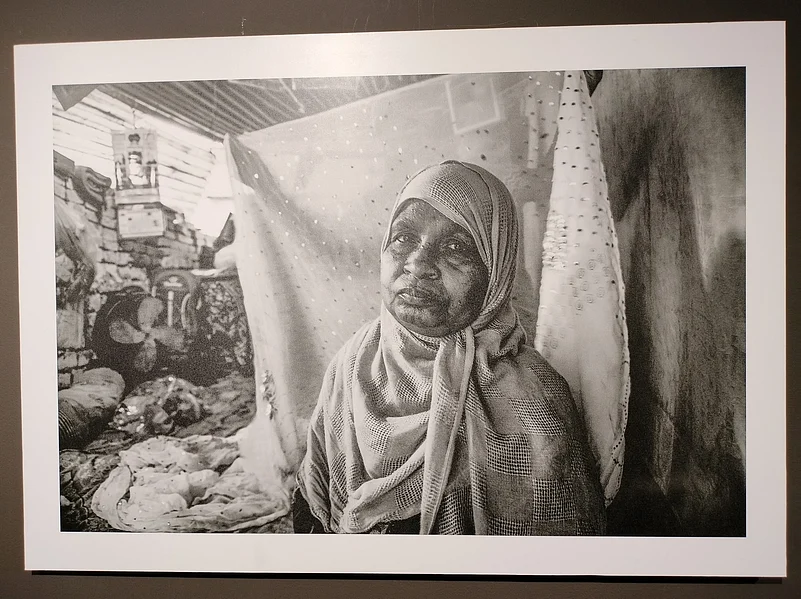

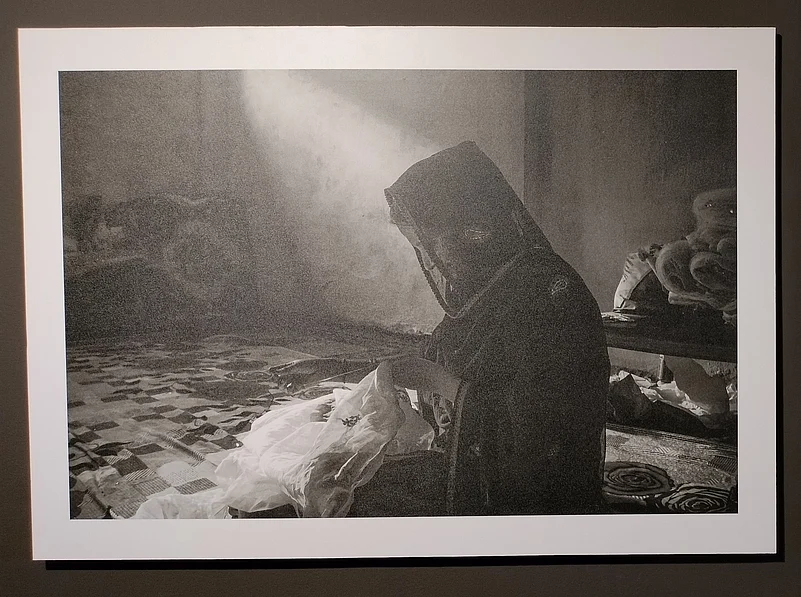

Juned uses chiaroscuro to reveal the intimate spaces where these artisans labour all day. Her pictures give a poignant impression of what it means to be trapped in a cycle of work which has no place for personal desires. Close ups of their hands, and the embroidery which they toil over, foreground their contribution to this endangered art, for which they are paid meagre wages. The series attempts to break away from the shadows within which these women dwell, bringing their faces to light in a literal sense. “The karkhana (factory) where the men work on muqaish is on the main road, accessible to the public eye,” says Juned. “They are commissioned by shopkeepers regularly and get better wages. But the dilapidated homes of these women hide in narrow gullies, which one person can barely enter at a time. This restricts their access to the outside world as well as better prices for their pieces.”

The young artist, a native of Lucknow, was inspired to do this photo series as the art has been in her family for generations. “I had always seen my mother and grandmother wear this work. One day, my grandmother brought out a beautiful green dupatta with intricate muqaish work all over and told me that it was her handiwork,” she recalls. “It struck me how the painstaking labour behind this striking art had not been recognised for decades.” It was this inter-generational tradition that also became an important thread in her photographs. “The tragedy is that these women have never worn a single piece of such clothing on their bodies. These pieces, which require ten hours of work per day, impact their eyes and backs and are expensive because of the metal prices”. Juned says that if given a choice, the artisans do not wish to pass on their skill to their children and want them to get educated instead. Her work also raises the question of agency—the women choosing to engage with this art out of joy, and not out of their need.

Fatima Juned’s process of working with these artisans is lucid in her series. The hesitation that governed the initial response of these women to Juned’s ideas has a marked presence in her photographs. Some of their faces are veiled by the pieces that they create in these pictures. “While the older women were more reserved, the younger ones agreed to be photographed eventually,” she recollects. “The process of easing them into the project was difficult, but the expressions I was able to ultimately capture were stark and raw. It was a lovely engagement.”

Juned hopes that her work will bring a change, however humble, in the lives of these women. Through her enduring engagement with these artisans, she is moving towards building a women-led collective where these women can get fair prices for their labour and sell their pieces directly to the market, without the mediation of middlemen. “If I can assist even a few of these women to stay with this craft for the joy they get from it,” she says, “then that will be my contribution towards slowing the rapid disappearance of muqaish.”

The exhibition is open for viewing at Museo Camera till 6th October.