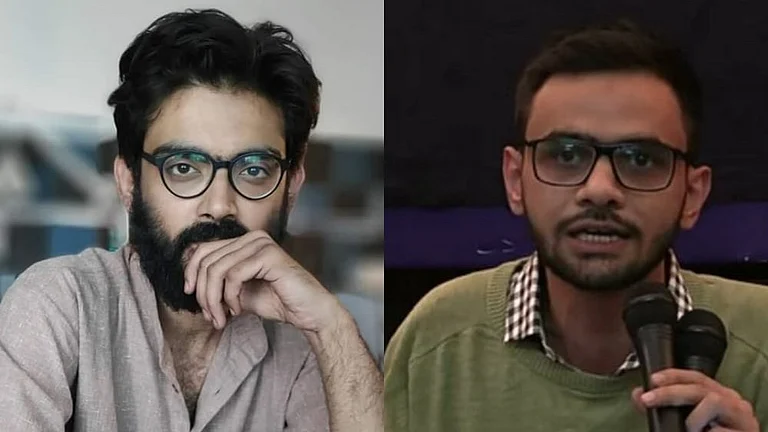

Student activist and JNU scholar Umar Khalid completed four years in prison last week, after being named as an accused in the 2020 Delhi riots. Khalid’s arrest has been among the most contentious ones in recent memory, even as dozens of political prisoners like him wait for their trials to begin. It would be almost too easy to call it Kafkaesque, but nothing else comes close to describing the utter incomprehensibility, confusion of the circumstances. Khalid has remained an undertrial, as multiple bail applications have been rejected citing his arrest under the Unlawful (Activities) Prevention Act, 1967 (or the UAPA). It was only a matter of time before Khalid would become a subject for a film.

Lalit Vachani’s Prisoner No. 626710 is Present charts Khalid’s journey from the JNU protests in 2016 (when he became a household name after being wrongly linked to a terror outfit by a TV anchor), to his arrest in 2020, months after the anti-CAA protests. Vachani’s film strives to be an intimate work where he interviews two of Khalid’s closest confidantes—his partner, Banojyostna Lahiri (also known as Bono), and friend, Shuddhabhrata Sengupta (also called Shuddha). Chronologically following the events in Khalid’s life between 2016 and 2020, Vachani’s film doesn’t dig too deep beyond headlines, including his appearance on Arnab Goswami’s primetime show, the attempt on his life, and him partaking in the nationwide protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019. However, Vachani’s film does capture our uncertain times, which will seem more significant a few years later, when we’re less desensitised.

Best known for his films on the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Vachani spoke to Outlook about key creative decisions around his film, his meetings with OTT platforms that steer clear of political content, and whether he wishes to ‘convert’ people’s opinion on Khalid’s arrest.

Edited excerpts:

Would you explain how you came about making a film on Umar Khalid?

I’ve been wanting to do something on Hindu nationalism and the RSS; I’ve made two in the past [The Boy in the Branch (1993), The Men in the Tree (2002)]. I had a nice conversation with my characters from my earlier films—two are still in the RSS, one or two have moved out. It just wasn’t crystallising into a project, because I think I was trying to make a big film. A film that tells you everything that the RSS is doing today, the canvas was just too broad. I was shooting for that till 2016. And only last year, did this idea fully crystallise in front of my eyes that instead of making one large film—why don’t I make a series of short films on Hindu nationalism and its effects on society?

It was what took me to someone who was the researcher on my first film around the RSS, Shuddhabhrata Sengupta. We talked about many things, and one of them was about his friendship with Umar Khalid, the chargesheet and the whole case. At some point, he said that I should speak to Banojyotsana. I interview her, and I’m under the impression that it will be a part of a larger project on the 2019 Delhi riots. I go back and look at the material, Umar’s speeches and how systematically he’s been depicted by Hindu nationalist forces in the years leading up to his arrest, is when the idea begins to crystallise in my head. That’s when I decided that this would be the first part in the series, whose working title is Hindutva ke Afsaane.

Were you ever tempted to tell Umar’s story from his birth, schooling—in a conventional chronology?

One of my team members did suggest this—but I thought that if I took that route, I would not be able to do justice to the material I had. For example, a colleague offered to share an interview they did with Umar around the time Batla House took place in 2008. He’s very young in that, he probably hasn’t even begun university around then. I knew my jump-off point for the film was always going to be the JNU protests that took place in 2016—because it was the first time that the media began taking part in this witch hunt around students (especially those from the central universities).

Did you ever feel the responsibility of not making Umar seem like a martyr – keeping his humanity intact in the film?

I don’t know how conscious I was about it while putting the film together—but one scene that really works for me, is the first footage we see of him talking about how he’s forgotten to pack slippers [Khalid jokes about how his haters might throw a pair of slippers at him, which he might be able to wear since he had forgotten to pack his own]. It’s just the ordinariness of it that I enjoy, he’s giving a speech—it’s not even anything political, but his sense of humour is terrific.

Another bit where he’s reading out the new things he’s learning about himself from the national media [linking him to a terror outfit, saying he recently went to Pakistan]—the irreverence sticks out for me. Even his friends like Shuddha, the way he argues for how there’s a place for Umar in our society [probably humanises him]. But I guess, it could be seen as a hagiography in a way because it’s genuinely coming from a place of appreciation for someone who is spending his best years behind bars.

Was Kanhaiya Kumar never in your radar for this film—considering they started out together?

No. Some people felt that he hadn’t responded adequately to Umar’s situation—he may have his own reasons for it. But yes, he has moved into another sphere altogether. It could’ve been an interesting addition, but ultimately I chose to stick to Umar’s journey.

Anyone following the news cycle will be familiar with a lot that’s there in Prisoner No. 626710 is Present. Do you think your film will play better when discovered 20 or 50 years from possibly a time capsule—when things are hopefully slightly better…

Or worse [laughs]. It’s an interesting thought for sure. This friend of mine at Columbia Journalism School was telling me about the scene involving Arnab berating and shouting Umar down on his primetime show. They said they watched it live, but were still shocked when it played. I’ve seen that clip hundreds of times in the process of making the film—and I’m still horrified, sometimes even angered by it. This journalist is obviously very proud of his performance—the disparity in our worlds is just surprising. The national media… I don’t think I see any difference between them and the Hindu nationalist media.

Logistically, were you hindered while making the film? I’m assuming you’re making a film like this at your own expense. Would you have liked a bit more support from a production house

I had a small grant from the university where I teach. I have spent some money out of my own pocket, because the post-production can often be expensive. But I’m in a fortunate space— where I have a full-time job, so I can always save some money to pour into my documentary. I haven’t really thought of a revenue stream. I think my hope is to show this film as widely as possible, and to mobilise people around the injustice being meted out to this group of young, promising individuals. I half-joking told some friends how we should try and show the film to the Chief Justice—only to get their response on what is going on within the justice system.

What’s your experience been with streaming services, production houses? Have you done any pitch meetings with them?

Mubi have me on their website, but they’ve never approached me. Netflix had approached me, I think, among the first wave of documentary filmmakers back in 2015-16. I remember saying that I would get back to them and never did. I was a bit conscious about my RSS films being circulated around, something I’ve grown more open to over the years. But Netflix won’t approach me now.

Looking at the political landscape, the sharp descent of TV journalism, the censorship – do you think we as a nation are more fraught, dishonest and corrupt than ever? Or do you think such things are cyclical in nature?

I hope it’s cyclical. I hope we’ll come out of this universe that we currently inhabit, where people talking about non-violence are put behind bars, while those in positions of power instigating violence roam around freely. I hope this changes. Of course, a lot of it has to do with this regime controlling institutions. I do hope there’s this deep yearning for true freedom. I’m hoping that people will see through how they’re being pitted against university students by branding them to be enemies of the state. I think it partly reflected in the [2024] election results.

What is the impact you’re hoping for this film to have on viewers—were you ever scared that you’re making this for an echo chamber? Are you hopeful of winning converts?

I hope this film can be the fulcrum for the conversation around the release of all political prisoners [not just Umar], who have been wrongly incarcerated for so long. I want people to see this incredible injustice being done to these people in the prime of their youth, forced to spend their time behind bars.

I think there are two levels to this—I’m making the film to consolidate the base. I don’t see it as an echo chamber, I think people who care for Umar Khalid have all the more reason to voice their dissent against the injustice he’s facing. There’s a large swathe of the population that simply doesn’t know enough to have an informed opinion on Umar Khalid. I see this film as a medium to communicate basic facts around his arrest. I shared the film with my families, and they were quite surprised to find out his speech was about Gandhi—since it’s clearly not what the mainstream media is portraying.

You’re never going to convince the Op-India crowd. They’ve already judged and pronounced his guilt. I don’t think this ideological gulf will ever be filled. I would be naive if I thought I would be able to change their minds. They will forever be critical of films like mine, While We Watched, Anand’s film (Reason), or Writing with Fire. Like we will be critical of their writing. It’s fine.