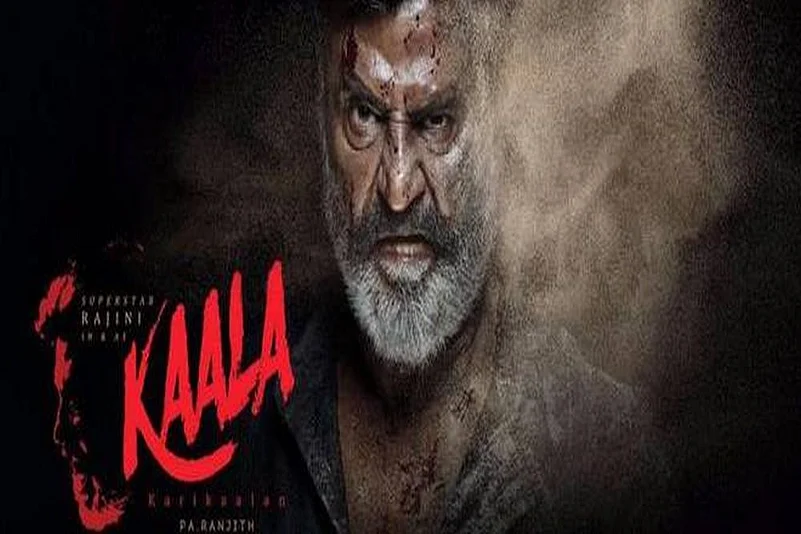

Director Pa. Ranjith has for the second time wasted Rajinikanth’s magical screen presence and fan following with yet another tepid storyline. In Kabali, the story happened in distant Malaysia, as Rajinikanth took on Chinese underworld dons. In Kaala, he battles a Marathi—Nana Patekar—to protect the rights of Dharavi slum dwellers of Mumbai to live on their own land.

To be fair, Kaala does not suffer the confusing screenplay of Kabali. But the latest Rajini movie’s presentation is linear with no surprises or twists in the storyline. And that robs it of any charm generally associated with a Rajini movie. Ranjith has penned politically-loaded dialogues for the superstar: they may serve him well in politics, but in the film they simply fail to add zing.

A comparison with Mani Rathnam’s Nayakan (also set in Dharavi) and Kamal Haasan’s award-winning portrayal of Velu Nayakar in that 1987 movie is unavoidable. While that film remains a classic, Kaala would register as a forgettable blip on Rajini’s largely glittering filmography.

Rajinikanth plays his age—he is even a grandfather in the movie as he is in real life—as the leader of the people of Dharavi, many of whom had moved from South Tamil Nadu like Kaala’s family. The film opens like a documentary on how the slum populace forms the backbone of any large metropolis, yet are the first to be thrown out of their homes under the name of beautification.

Building on this theme, he shows Karikaalan alias Kaala leading the resistance of the locals to redevelopment plans of Hari Bhai (Patekar), a powerful right-wing politician of Maharashtra’s ruling party. The entire film is about the tit-for-tat between the two. Rajini kills the right-hand man of Hari, gets a proxy to surrender in court and virtually imprisons Hari in Dharavi when he comes to visit him. Hari responds by getting Kaala hauled up to the local police station and then lets him go only to target him by ramming trucks into his jeep. While Kaala survives, his wife and eldest son are killed.

Kaala then visits Hari at his home, only to warn him that for the poor land is livelihood while for the rich it was power. Hari responds that he has been after power his entire life. Kaala challenges him that he cannot take away even a fistful of sand from Dharavi, following which Hari’s henchmen burn down the houses. In retaliation, Kaala organizes a strike of workers: cab drivers, sanitation workers and the rest of the working class who live in slums like Dharavi. So Hari sends his goons and police to Dharavi who attack the residents and apparently kill Kaala in a bloody confrontation. As a triumphant Hari prepares to do bhoomi puja at Dharavi, Kaala materialises and foils Hari’s takeover of the slum.

Rajini has done full justice to his role, but more as the family man, romancing his wife (Eswari Rao) and looking embarrassed in the presence of his first love (Huma Qureshi). As a don, there are hardly any incidents to prove his heroism or quick thinking to outwit the villains. And most of the time his powerful and piercing eyes are hidden behind dark glasses. Otherwise he is only shown driving a jeep, sitting cross legged in front of his house with a mongrel and walking into the frame in slow motion.

The acting honours belong solely to Eswari, who comes as the feisty wife who even tolerates Rajini’s former love re-entering his life. The few laughs that the film generates are due to her. Patekar has been wasted by mouthing irrelevant lines comparing Rajini to Ravan, while closer to climax he is shown as a Ram bhakt, as director Ranjith tries woefully to juxtapose the Ramayan on the script.

The other two heroes of the film are art director T. Ramalingam, who has recreated Dharavi in Chennai and cinematographer Murali G., especially for the climax filled with different colours. Director Ranjith’s symbolism is growing tiresome as he uses the colour black, a Buddha Vihara and an Ambedkar statue while giving vent to the voices of the suppressed. Not many directors get to work with Rajini in two successive movies. Ranjith got the rare chance and he has blown it away. Rajini’s political entry will be marred by yet another flop and he now needs ace director Shankar’s ‘2.0’ to rescue his superstar image.