The colours were truly of another world, which would seem almost unreal now. The sea was really blue. The sky above it those days had a chirpy brightness, in sharp and happy contrast to the grey, dusty, noxious umbrella that hangs over wintry Delhi now. The sandy strip called Andrott did sport an occasional dune by the shore; otherwise my island was like any other in Lakshadweep: flat, as the Quran said the shape of the earth was. All houses were thatched with braided palm fronds—from some angles they looked like dwarf coconut trees themselves. We too had one such dwelling, but it suffered severe damage in a cyclone. That was the year I was born: 1941.

Lakshadweep Diary

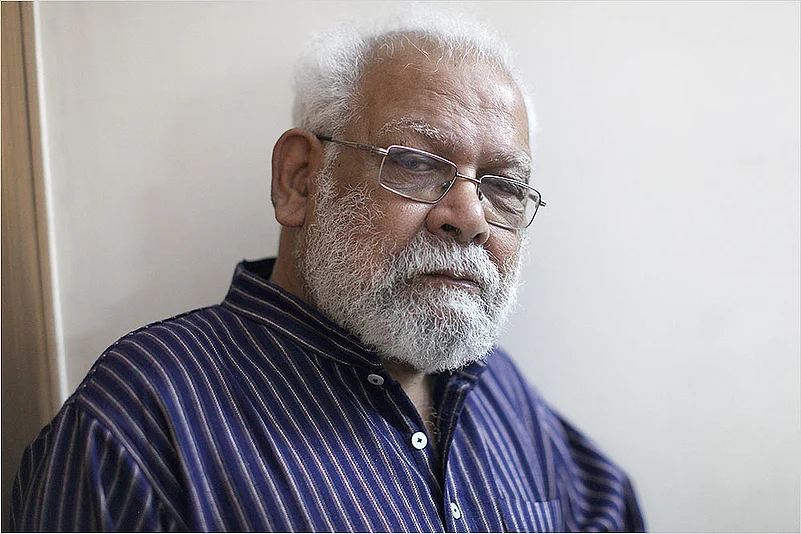

"Life for us was an honest, open book. Uncomplicated, steeped in mutual trust. No house had doors in the front or back. Neither did the women wear purdah," reminisces surrealist painter NKP Muthukoya

Our family weathered the crisis; so did all the folks around. My father, Sayeed Koya, was an all-rounder. He did calligraphy at the neighbourhood masjid, he was also a goldsmith-blacksmith. So the visual arts, as also the embodied world of craft, touched me early in life. Life for us was an honest, open book. Uncomplicated, steeped in mutual trust. No house had doors in the front or back. Neither did the women wear purdah. It was great fun on certain forenoons when we’d be told of a mini ship with goods nearing the coast. Men of all ages would rush through the shallow stretch of lagoon with long, thick ropes to the raft waiting at the mouth of the open sea, onto which cargo would be unloaded. A minute’s boat-song will rend the air, after which we’ll pull in the wooden float. Both my parents had an immediate Kerala connection that should have ideally made us rich, but for abrupt deaths in the family. Matrilineal laws worked against them. They sensed prosperity in the mainland. Soon we were to move to Malabar.

I was still a toddler when our family chose to venture east and hit Kannur, where we had relatives in the royal Arakkal household. But it wasn’t together that we travelled. First left a boat carrying my parents and a sibling; only a day later could my grandma board hers, holding me. Inside, the stench of sweat and grime made me queasy. I began to scream, annoying all the co-travellers. When they couldn’t bear me anymore, someone shifted me onto a small canoe towing alongside the boat. My grandma was crying out in anxiety; my voice under that glowing sun was perhaps even louder.

Life in Pazhayangadi, 15 miles north of Kannur, wasn’t all that bad. I joined a local school. From class 8 onward, I studied in Kozhikode. By then, my parents had returned to Lakshadweep, failing to flourish in Kannur. My footsteps, though, were destined to head towards a metropolis.

At Madras in 1960, it warranted a last-minute gatecrash before I could become a student in the Government College of Fine Arts. I was a good 24 hours late for the five-day entrance test! The iconic K.C.S. Paniker, who was the principal, was accommodative enough to take me to the hall crowded with aspirants, all busy sketching and painting. I cleared all hurdles, but was clueless about accommodation. A nearby mosque did permit overnight stay, but the muezzin’s call would wake you up ahead of the pre-dawn prayers! Luckily, I met Raghavan, an old classmate from my Kannur days whose father was running a roadside tea-shack at a nearby intersection. They served me food, we slept on pavements. After six months, I found a dormitory at Triplicane, and stayed with college-mates who later gained fame: Kanai Kunhiraman, K. Damodaran, V.M. Sasidharan. It was a whole new world, with study tours to other cities opening up more windows and landscapes. That six-year course sowed the seeds of my blooming as a surreal painter.

I returned to Lakshadweep and found an art teacher’s job. I was prone to making heretic comments, much to the ire of the mullahs. In 1968, Indira Gandhi, as prime minister, visited Andrott. I presented her a painting. As an art-literate person, it triggered curiosity in her: a modern artist in a primitive pocket! Two years later, I landed in Delhi. Cartoonist Shankar gave me a break as an illustrator in Children’s World. My next stop, too, was a magazine: Caravan. In 1973, I joined the Directorate of Advertising and Visual Publicity: what in the old days they’d call “a proper job”.

Those early Delhi days had a touch of Parisian Left Bank for me, thanks to the top Malayalam writers who were my city-mates. O.V. Vijayan, working as The Statesman’s cartoonist, would come over for neychoru, our Malabar delicacy. Still earthier was novelist M. Mukundan…and poet Kadamanitta had a year-long stint, an eventful one for all of us! I also forged enduring bonds with Kakkanadan and Punathil Kunjabdulla, who died this October. As for Paul Zacharia, we made merry like the old days only the other week, when he briefly came to Delhi. All through my working years, I took time off to paint. I still do, two decades after retirement.

While in service, some bureaucrats treated me like an illiterate craftsman. For them, painter meant nothing more than a signboard colourer. Muthukoya, the Madrasi labourer. I’m thrilled to sniff a sweet revenge today. In Kerala, my second home, Kochi-Muziris Biennale is through with three successful editions of what is now India’s biggest contemporary art show. Conceiving it requires a mind that can fuse entrepreneurship with art optimally. A new generation down south has succeeded where I had failed. Kudos!

(The writer is one of India’s first surrealist painters)

- Previous Story

The Friend’s House Is Here Review | Sisterhood, Solidarity And Art Prevail In Sparkling, Free-spirited Iranian Drama

The Friend’s House Is Here Review | Sisterhood, Solidarity And Art Prevail In Sparkling, Free-spirited Iranian Drama - Next Story