Aditya Nimbalkar’s Sector 36 sifts through the 2006 Nithari killings, which it is “inspired” by, scrounging out just the perturbing aspects. The case has all the ingredients of what the streaming platforms seem to lap up-gruesome murders, sexual abuse, necrophilia and cannibalism. Scores and scores of kids and young women went missing from Nithari, which becomes Shahdara in the film. Victims were from lower-income, migrant settlements, lacking the means to push for a continued investigation. Sector 36 acknowledges the question of class and economic power linked to the case, but its prurient indulgence sidesteps sociological scrutiny.

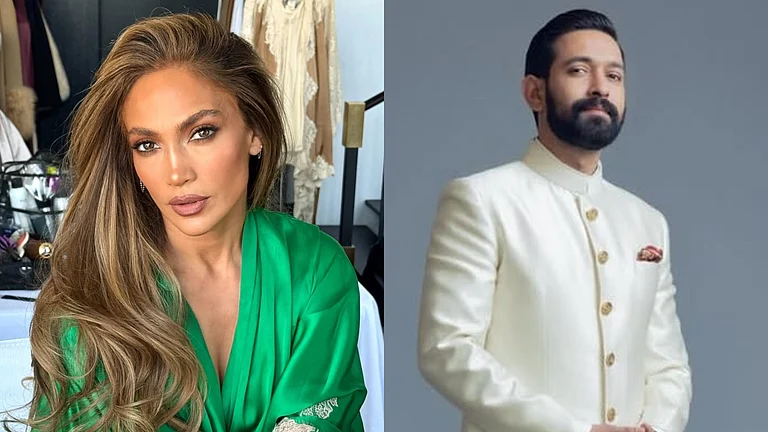

Sub-inspector Ram Charan Pandey (Deepak Dobriyal, mostly blank-eyed apart from a righteous rant) has a blasé attitude to the routine disappearances. He wards away the parents of the missing children with a lump of cash. It’s only after his own daughter narrowly escapes a kidnapping that he decides to pursue the chain of mysteries. Conversely, this isn’t some drama about the hunt for a serial killer. Once Pandey gets serious about the crimes, he cracks it quickly. The killer, Prem (Vikrant Massey), revealed in the first scene itself, is the caretaker at the mansion of a wealthy businessman and transport mogul, Bassi (Akash Khurana). Bassi’s complicity also becomes apparent but his access to power corridors, influential connections grant him immunity.

Nimbalkar locates several degrees of collusions and cover-ups between the justice machinery and privilege. But the portrait of urban decay and institutional indifference bumps too often against the makers’ obsession with the gratuitous. Severed, rotten body parts, dredged-up bones, officers throwing up at the moment of discovery-the camera fixates on them to reinstate the revulsion in the murders. It is this diligence of the film to keep us queasy that blindsides it from any kind of ideological curiosity.

In a long monologue, designed as the film’s centrepiece, Prem defends himself as offering “salvation to the lowlifes”. Massey bites especially into the chilling insouciance of a psychopath’s confession. Prem rattles off a count of victims without any qualm. It doesn’t strike him as monstrous but a necessary cleanser. With unaffected confidence, he explains how all he does is rescue “unwanted” kids from a future of no notice. Nimbalkar sets up the confession scene as a showcase of actorly exhibitionism. Massey revels in this. As he keeps slicking his hair into place and proceeds to leap about enacting a strangulation, the scene slops into a mere performative highlight.

Massey’s performance occupies a peculiar, distracted remove from the rest of the film. Though the film conspicuously underlines a wider, institutional rot which triggers suchcrimes, the performance is too unmoored, vaunting itself amidst a vacuum. It doesn’t help the bungalow in which Prem slaughters is an insipid derivation of generic serial-killer dramas. Gross under-realisation within the screenplay extends to fragmented scenes of the attacks, skittering between the unnecessary and the downright questionable. Nimbalkar centres these while disposing of an emotional throughline is the film’s most fatal blunder. The film views the murders in dispassionate terms as just body count.

For the most part, Sector 36 weaves in and out of various sites-the house where the murders took place, those of the victims and the hospital to which their organs were parcelled out. But these shifts further deflate the perspective of the-dishonest-turned-conscientious-cop through which Sector 36 is filtered. Prem gets a backstory too of a childhood torn by sexual abuse; this dishes out in a tacky, lurid flashback. Nimbalkar’s lazy, slapdash handling dilutes all the restless toggling even when the film calms down in the second half.

The screenplay’s reluctance in fleshing out thematic queries also surfaces in an abrupt minor thread where a rich kid gets kidnapped. The family’s affluence ensures the case gets national attention and the kid rescued in two days. Pandey’s superior schools him in taking up such “productive” cases which would be a career boost too. Insertion of this ‘rich kid’ plot, which wraps up within few minutes, comes off as a blunt reiteration of prior established home truths. Corrupt, slimy police force eager to swat away the problems of the poor is one of the very first things the film addresses. Early in the film, Pandey, before his conscience is jolted and he turns a responsible officer, calls this entrenched sense of injustice the key facet of the system. You’d better accept it and act accordingly.

Sector 36 is dehumanising filmmaking, troublingly settled in grotesquery divorced from a basic urge to understand or empathise. Even in the detail-heavy monologue of Prem, where all his misogyny and twisted logic explodes, you wonder what’s the purpose of it all. The film shuts out the voices of the victims’ families. The one it chooses to contain is a distraught father who pimped his daughter to Bassi. The screenplay confusedly fluctuates between an outright condemnation of the father and a weak assertion of his right to justice.

Essentially, Sector 36 is unable to extricate itself from the voyeuristic, sensationalist bent to the way such cases are reported in mainstream media. In a later scene, Nimbalkar castigates the tone of such media coverage. It’s an amusing irony because there’s little difference between that and the film’s penchant for the exploitative.