When 21-year-old artist Mureen Shahmiri assayed the role of a Kashmiri militant in the 2024 film Operation Valentine, driving an SUV loaded with explosives zeroing in on a vehicle with security forces, little did he know, he would be the object of ridicule in viral memes.

Shahmiri, a journalism student, landed the role of a militant in the film, based on India’s cross-border airstrikes in Balakot, soon after he played an onscreen informer to the armed forces in another TV series, Rakshak (2023).

While his film career slowly takes shape, Shahmiri has garnered more attention offscreen, dealing with trolling and memes, by those who criticise his film roles, labelling them as negative for Kashmiris.

Shahmiri insists that he simply portrayed the character as an actor in the film, distancing himself from endorsing any particular viewpoint or ideology.

“When I was offered this small role of driving a vehicle with explosives and acting like an angry Kashmiri who had to blow up himself, I was a bit reluctant. I talked to various actors. They suggested that I should go ahead with it,” he explains. “I am an artist and I tried to act as an artist. In the future, you will see me in better roles,” he adds. However, after a moment of contemplation, he expresses his preference for roles portraying a romantic hero or a saviour rather than negative characters, emphasising his aspiration as a Kashmiri artist.

With numerous filmmakers choosing Kashmir as a shooting location and some producing films centred around the region, Kashmiri artists are now actively participating in auditions. “When filmmakers come to Kashmir to shoot and especially if the film revolves around Kashmir, they require Kashmiri artists, we step in to bridge that gap,” Shahmiri says.

However, the projection of Kashmiris in Bollywood cinema has prompted viral Instagram reels, including the one titled ‘Kashmir Muslim in Real Life vs Kashmir Muslim in Bollywood,’ which has garnered 3.1 million likes and 20 million views. The 30-second reel begins by depicting a Kashmiri boy casually sitting on a motorcycle, smiling and browsing through a market, appearing completely normal. However, as the reel transitions to ‘Kashmir Muslim in Bollywood,’ the same boy suddenly appears anxious, constantly looking around and making phone calls, giving the impression that he is about to commit a crime. While the music in the ‘Kashmir Muslim in Real Life’ segment is serene, the music in the ‘Kashmir Muslim in Reel Life’ portion changes abruptly, creating tension.

According to Kashmiri poet and actor Bashir Dada, before the 1990s, Kashmir was portrayed as a paradise of breathtaking beauty, featuring Shikara rides, houseboats, magnificent Mughal gardens, and costumes. During this period, Kashmiri characters in movies were often depicted as impoverished individuals who relied on charity.

Local entrepreneur Abdul Hameed, a film enthusiast, recalls a scene from the 1965 film Mere Sanam when he witnessed the recent felling of beautiful poplar trees at Amar Singh College. The scene from the film’s song Pukarta Chala Hoon Main features Biswajit Chatterjee driving a jeep while Asha Parekh rides a bicycle, surrounded by lush poplar trees, capturing the essence of Kashmir’s beauty. “I only remember this,” he adds.

Dada says Kashmir represented peace and solace visually and the only visuals about Kashmir were those that brought its beauty to the fore. “Even the beauty was projected as if Kashmiris don’t deserve it,” he adds.

Kashmiri scholar, Mudabbir Ahmad Tak, says cinematic representations of Kashmir and Kashmiris in mainstream Indian cinema are fraught with problems. Tak says one of the most commonly observed motifs in films about Kashmir is its geographical beauty. “In the Bollywood films of the pre-1990 era, Kashmir was depicted as an exotic place, where beauty was the only aspect worth representing. This included the geographical beauty of the place, as well as the physical beauty of the people.”

“Films such as Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965) and Kashmir Ki Kali (1964) depicted Kashmir as a visually stunning place of physically beautiful people, but empty of other cultural and societal aspects. The people were depicted as dumb, simplistic, naive and ancient,” says Tak.

“In films such as Jab Jab Phool Khile, Kashmiri characters could not even properly speak any language—it was comical when they spoke English—their Urdu or Hindi too was tinged with a strange accent and because these characters were played by non-Kashmiri actors, their Kashmiri was absurdly out of place,” Tak says.

After insurgency erupted in Kashmir, the connection between Bollywood and the region changed dramatically.

“Emptying Kashmir of any cultural markers, the films of the pre-1990s era reduced Kashmir to a single aspect—beauty. This beauty was there to be enjoyed by the non-Kashmiri characters in these films. This led to the ‘exoticisation’ and ‘fetishisation’ of the place in these films,” he adds.

After insurgency erupted in Kashmir, the connection between Bollywood and the region changed dramatically. Previously portrayed as a peaceful paradise, post-1990s Kashmir in Bollywood became politicised. According to Amin Bhat, president of Adbi Markaz Kamraz, a prominent literary organisation in Kashmir, the portrayal of Kashmir and its people shifted significantly. While the pre-1990s films focused on beauty, the post-1990s cinema depicted both the land and its natives negatively.

As violence consumed Kashmir after 1990, mainstream Indian cinema associated mindless violence with the region, devoid of political context. Violence became a spectacle in films like Roja (1992), The Hero (2003) and Mission Kashmir (2000), linking it to the destruction of Kashmir’s beauty. These films portrayed violent acts without historical context, attributing them to misguided individuals from a specific community. By eliminating the political backdrop, Bollywood ‘spectacularised’ Kashmir and its people, reducing them to mere subjects of entertainment. Post-1990, Bollywood thus contributed to the ‘sensationalisation’ of Kashmir and its plight.

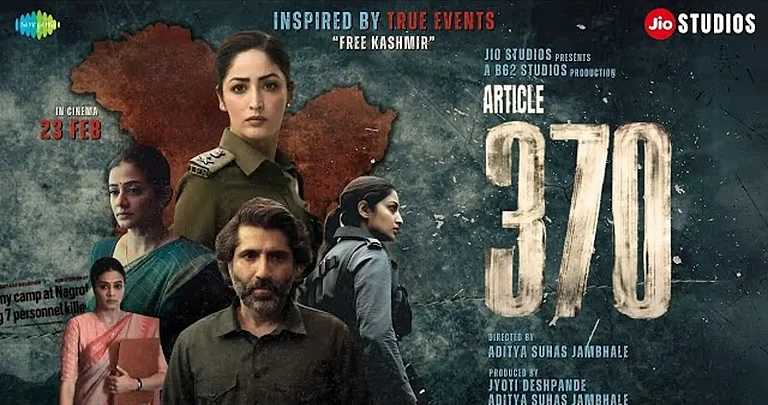

Experts say that post-2019, however, cinematic representations of Kashmir are being weaponised to rewrite history and envision a fictional future. Movies like The Kashmir Files (2022), Fighter (2024) and Article 370 (2024) distort reality through revisionist narratives. They exhibit Bollywood’s unhealthy obsession with Kashmir, stripping it of cultural, historical and political context, erasing the identities of its people. This trend empties Kashmir of its essence, perpetuating a dangerous narrative that undermines its rich heritage and complex reality.

For popular Radio Host Vijdan Saleem, Bollywood’s portrayal of Kashmir cannot be limited to The Kashmir Files alone. “Films like Haider (2014) explore the human stories behind the political turmoil, capturing the emotional struggles and resilience of Kashmiri individuals amidst the changing socio-political landscape,” he says.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Tahaan (2008), directed by Santosh Sivan, according to Saleem, elaborates on this aspect, offering a poignant portrayal of the impact of conflict on ordinary people, particularly children. “Set against the backdrop of the Kashmir conflict, Tahaan provides a sensitive and intimate portrayal of the daily struggles and aspirations of individuals living in the region,” says Saleem.

(This appeared in print as 'Movies And A Mirage')