Six years after K.R. Mohanan made a movie that turned out to be his last, a fellow director from Malayalam employed an identical plot in what became a huge box-office success. The maker of that 1998 film, interestingly, acted as the protagonist in Mohanan’s swansong on the celluloid.

Mohanan, who won critical acclaim for his Swaroopam (1992), died his native Kerala earlier this week after a bout of ailment. At 69, his end cast a gloom in Mollywood even though it was as an administrator, film-festival organiser and television programme head that Mohanan primarily sustained a reputation in his last two decades.

The core story of Swaroopam finds faithful replication in Chinthavishtayaya Shyamala, which is written and directed by the popular Sreenivasan, who appears as the main character in both the films. If Swaroopam won that year’s national award for the best feature film in Malayalam, Chinthavishtayaya… received a pan-India honour for the best film on other social issues.

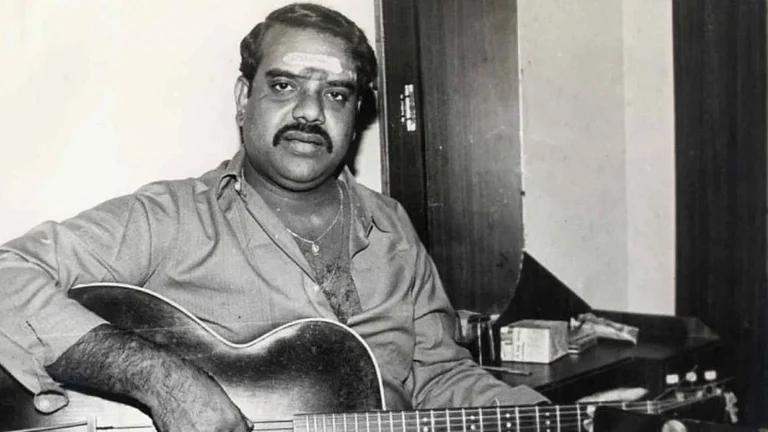

(A still from Swaroopam )

So, what is central theme in the two 1990s movies released in a state where art-house works and commercial hits often tend to blur borders? Well, it’s about an inexplicable change in the mindset of its hero — from being a breadwinning husband in the family to someone who becomes irresponsible in the guise of a new-found love for spirituality.

Amid the bewilderment he gives to the spouse as well as kids, the wife tries her best to get the man back to his ‘normal’ state—only to fail and then muster the wits to stand on her own for the benefit of the little daughters. Well, Chinthavishtayaya… goes for a brief extension of this situation by eventually showing the household’s head resume his good old working-days routine. On that (alone), Swaroopam differs: the 90-minute film climaxes with a distant shot of the housewife engaged in an outdoor assignment that symbolises the heaviness of the yoke that has fallen on her.

Now, the theme is not all too common—definitely in Malayalam with a talkie history of eight decades. Neither is its overlap in the two movies peripheral (even a YouTube link to Swaroopam carries a comment wondering if the film later led to the making of Chinthavishtayaya…). What’s more, the obvious repetition of the idea made it to the silver screen in little over half a decade, which guarantees no time to forget the first, leave alone a generational change with the viewers.

(A still from Chinthavishtayaya Shyamala)

Yet, the striking resemblance was least as an issue in Mollywood. Neither spectators nor people in the industry even discussed the matter publicly. What does it imply? Either, that Swaroopam, which is Spartan in looks and progresses at a slow pace, was not viewed by many. Or, that Mohanan the director, who also wrote its story, chose to keep mum on what could have become a point of debate at least for a short time. (The hero in Swaroopam is clean-shaven in his ‘pious’ phase of life, while in Chinthavistayaya… he is bearded; so what?)

That said, Chinthavishtayaya…is perhaps a smoother film to watch, even without the masala that is anyway part of mainstream Indian cinema. The 158-minute work, woven around Vijayan the fickle-minded schoolteacher swayed by his pals, has a row of better actors, colourful progress of the plot and juicier visuals vis-à-vis Swaroopam. I

t simply puts a reluctant pilgrimage to the Sabarimala hill-shine as what led to the hero’s sudden turn to mysticism. (The movie got a 2005 Tamil remake, Chidambarathil Oru Appasamy, which was also a commercial hit.) Contrastingly, the Mohanan film leaves more scope to ponder over this side of the story. The director, on the face of it, relates it to the protagonist stumbling upon certain details of his ancestors, but that leg of the story runs on frames that have a subtle feel of fantasy. It is up to the viewer to decide whether the young farmer actually meets members of his extended family up north of his village, where he largely leads a cut-off life. Maybe Sekharan was only imagining things, having perhaps had a subconscious desire to trace his close relatives about whom he had no clue.

Notwithstanding this infusion of a deliberate loose thread, Swaroopam largely comes across as a work wanting in quality. Quite a few of its scenes suffer from finish, leave alone flourish. The initial shots seek to plant the idea in the viewer about rustic Sekharan’s family busy with farming, poultry and raising cows, but with a string of inadequacies least expected from a director who has great regards for the perfection-aiming Adoor Gopalakrishnan school of filmmaking. Of his two feature films prior to Swaroopam, one (Aswathama, 1978) is in black-and-white, while Purushartham (1987) has also been rated highly. The filmmaker breathed his last on June 25.

On the personal side, mildness was a defining feature of Mohanan, who was born in the coastal Chavakkad village near Guruvayur and had graduated from Pune’s Film and Television Institute in 1973. His close friends in Thiruvananthapuram where he had settled did prompt the filmmaker to speak openly about the thematic copying of Swaroopam, but Mohanan reportedly took it lightly, saying one can’t prove such things.

Apparently, the aesthetics of cinema alone topped Mohanan’s interests all his life.

.jpg?w=801&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&dpr=1.0)