This year’s National Film Awards featured several shocking choices. But even among them, The Kashmir Files stood out for bagging the Nargis Dutt Award for the Best Feature Film on … National Integration. An Islamophobic rant winning such an honour is remarkable, but the idealistic award category sounds equally fascinating. It’s not always been a part of the National Awards, and it didn’t have the same name either.

Instituted in 1965, it was first called the Best Feature Film on National Unity and Emotional Integration—a phrase often used by Indian politicians then. “I’d appeal to each one of us,” Nehru said, addressing the public servants on July 10, 1961, “to work continuously and deliberately for the promotion of national unity and emotional integration.” He wanted to vanquish the evils of communalism and “linguistic differences”—and, as his other speeches and writings indicate, also casteism and regionalism—to “build the India of our dreams”. In the next month, he convened a conference on national integration—inviting all the chief ministers—and organised another conference, on a bigger scale, in September 1961, creating the National Integration Council (which, at least in theory, is still functional).

Vice President Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan echoed that ethos in his inaugural address for the second International Film Festival of India on October 27, 1961. “Films are a great instrument of inter-cultural understanding. In our country, it can contribute to national integration.” The early ’60s saw crucial changes that affected the landscape of Indian cinema. Implementing the suggestions of the 1951 Film Enquiry Report, the government created the Film Institute of India and the Film Finance Corporation (which became the FTII and NFDC in the ’70s). Besides, it had already instituted a National Film Award—then called the State Awards—in 1954.

Cinema had to move beyond entertaining the masses, as many leaders (including Nehru) often said, and contribute to national advancement—and integration. President Radhakrishnan emphasised that bond in his April 1963 speech, while distributing the State Awards for Films. “I’m glad to notice that we’ve had men and women of all languages, of all communities, represented among the recipients of awards. This, by itself, should be taken as an instrument of national integration.”

On January 11, 1964, The Gazette of India, a public journal and an authorised legal document of the Indian government, published a resolution of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. “With a view to encourage the production of feature films aimed at promoting national unity and emotional integration in the country, the government has instituted a cash prize of Rs 20,000.” Three movies competed for the honour that year, with Manoj Kumar-starrer Shaheed, a biopic of Bhagat Singh, emerging as the winner.

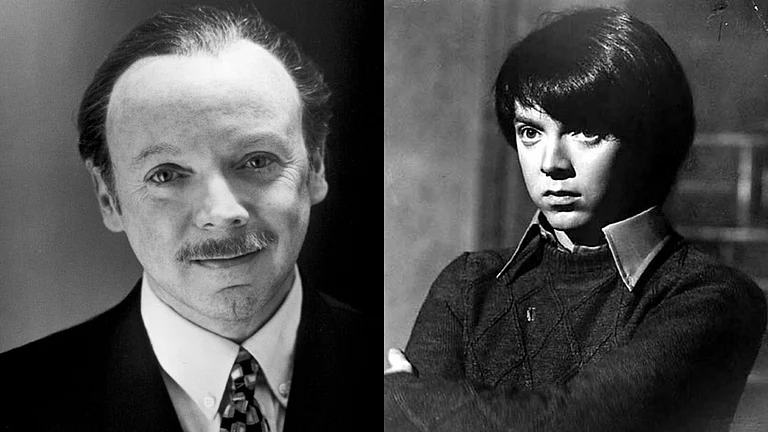

Its initial recipients included such iconic figures as Khwaja Ahmad Abbas for Saat Hindustaani (1969), MS Sathyu for Garm Hawa (1973), and Kaifi Azmi for the Best Film Song on National Integration (an award that was discontinued later). Quite curiously, no film won during the Emergency. A year after Nargis Dutt’s death, in 1981, the government renamed the prize in her honour, calling it the Nargis Dutt Award for the Best Feature Film on National Integration. The name change seemed befitting for at least two reasons: Dutt was a renowned actress whose diverse roles signified the unifying purpose of cinema—she, after all, helmed Mother India (1957)—and her father, a Hindu, had converted to Islam to marry her mother, exemplifying inter-religious porosity.

This history sharpens the disconcerting edge accompanying The Kashmir Files’ victory and casts light on the astounding omissions from this year’s awards. Because the National Integration Prize once encompassed the broader meanings of countrywide cohesion, recognising movies not just promoting secular ideals but also combating the narrow-mindedness of caste, region, and language. Bhavni Bhavai, for example, won the award in 1980 for “tracing the history of the social evil of untouchability through a popular folk drama” and “depicting the untouchables’ fights for their rights.” But this year’s jury for fictional films—chaired by the director of Bhavni Bhavai, Ketan Mehta—found no merit in several stirring anti-caste dramas, such as Jai Bhim, Karnan, and Sarpatta Parambarai.

Maybe that happened because, in the India of 2023, the words “national” and “integration” carry very different meanings. Just look at The Kashmir Files’ box-office earnings: Rs 297.53 crore. Or The Kerala Story’s (a solid contender for the next year’s award): Rs 242.2 crore. These films’ uneasy relationship with facts tells us that a vast majority of the audiences no longer throng to theatres to find out social and political truths. The nation already knows; now the nation wants to confirm.