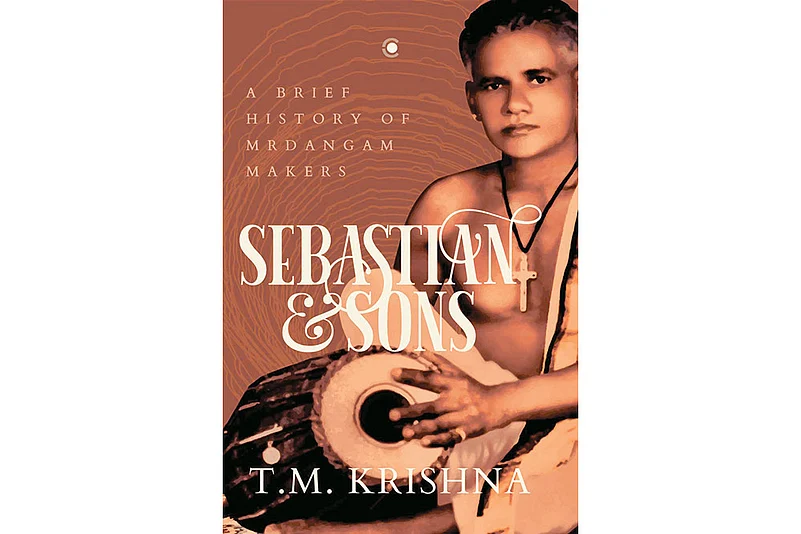

A recent article in The Friday Times of Pakistan lamented the plight of tabla makers of Peshawar, who faced extinction because of tabla being considered ‘haram’ by Islamic conservatives. Mrdangam, on the other hand, is considered sacred in South India and its makers are nowhere near extinction. They are in fact thriving. But their domain is isolated, rarely frequented by the artists who use their products. Krishna sets out to explore it in Sebastian & Sons: A Brief History of Mrdangam Makers.

The mrdangam, a percussion instrument, is a cylindrical two-faced drum, with a hollow resonating chamber made of jackfruit wood, its sides covered with layers of cured cow, buffalo and goat hides. Its users are almost all Brahmins, while an overwhelming majority of its makers are Dalits. Krishna visits them, observes their work keenly and tells us in detail the technicalities involved in making a good mrdangam. If the warp of Krishna’s weave is the reminiscences of the makers and their families, the weft is the tales told by the users. The resultant fabric is arrestingly bright, but uneven and rough on touch in places. The author’s meandering style engages our attention till the very end. Though the title says it is a brief history of Mrdangam makers, it is really about the relationship between the makers and the artists. Curiously, many of the makers who speak are still with us, but its main artists either long gone or dodderingly old.

If we were to pick two protagonists, they would be Palakkad Mani Iyer, the greatest name in Mrdangam, and the maker he sought after, Parlandu. Iyer died in 1982 and Parlandu in 1970. Since they hadn’t left behind any record, Krishna depends on the memories of the persons close to them. Mani Iyer was kind to Parlandu, in a feudal, patronising way: “A musical bond held Iyer and Parlandu together and created a personal closeness. But Mani Iyer could not transform this relationship into an equal friendship.” Parlandu was spontaneous and sure of himself. “Through the making process, the maker himself would have tested pitch accuracy over and over, but the moment the playing hand changes (from maker to artist) everything can go awry. Parlandu’s brilliance lay in making an instrument belong to the artist who owned it.” The problem with such narratives is that they can never be objective. Personalities pulled out of tunnels of memory will hardly look like what they were in real life. The book would have been infinitely more substantive if the author had spoken to young artistes like Anantha R. Krishnan, Manoj Siva and Akshay Anand about the modern scene.

Krishna also speaks about neglect of Parlandu and non-Brahmin mrdangists like Palani Subramania Pillai and Murugabhoopathy. While it is true that they did not get their due primarily because of their castes, it is not that all lovers of music ignored them. Parivadini, an organisation devoted to music, has been awarding percussion instrument makers since 2013. The award is in the name of Parlandu. Lalithram, the prime mover of Parivadini, has published a fine biography of Palani in Tamil. He also organised the centenary celebrations of Murugabhoopathy.

A violinist does not become famous just because he uses a Stradivari. Conversely, lovers of jazz know Louis Armstrong, but only a few know about the Henri Selmer of Paris who made his trumpet. When a person admires Armstrong’s wizardry, she instinctively understands that the music that emanates from the instrument is uniquely Armstrong’s and none other can produce it. The instrument does play a part, but we realise that in other hands it will never be as magical. The world of Carnatic music is much smaller than that of western music. It is exclusively peopled by Brahmins, especially in Tamil Nadu, a situation which Krishna is passionately seeking to change. As of now, hardly 10 per cent of the two million Tamil Brahmins will be interested in classical music and only a tiny portion of that 10 per cent will be interested in the social history of instrument makers. The mrdangam makers are doubly damned because of their castes. Viewed in this perspective, Krishna’s book is an important milestone in that it remembers the ones who ought to be remembered.