If you have a bittersweet longing for something absent in your life, or you have experienced something once, loved and lost, and may never experience it again and are left with feelings of love, happiness, sadness, hope, emptiness and desire—and if you speak Portuguese—you would say you are feeling saudade. It is the ‘pleasure you suffer, an ailment you enjoy’. Alas, there is no equivalent for it in English. As there is none for the Russian word toska, which in Vladimir Nabokov’s description is: “At its deepest and most painful, is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning.”

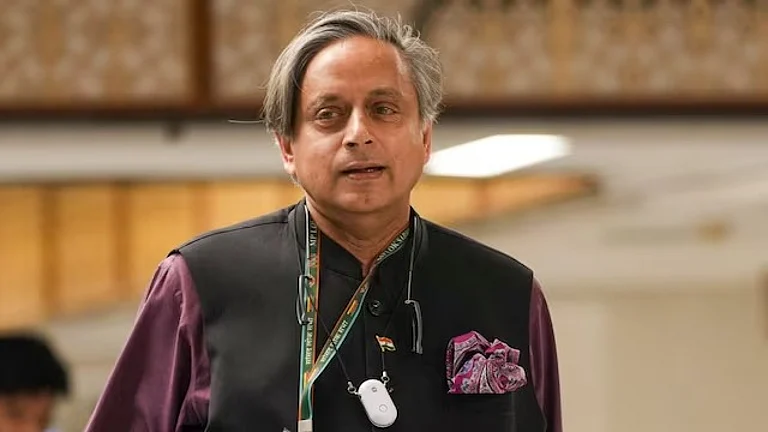

There are gems like these in Shashi Tharoor’s latest ‘verbal callisthenics’, the only kind of exercise he says he can do, A Wonderland of Words. The book has 101 short essays on words, written for the Dubai-based newspaper Khaleej Times as a column, divided over 13 sections like ‘Spelling Bugs’, ‘Linguistic Registers’, ‘Lexicon Evolution’, ‘Beer and Skittles’, ‘Master of Mirth’ and so on. The muscular book of over 400 pages is so addictive that you will reluctantly put it down after breakfast only to pick it up again at lunch. You may at first think you can skip essays with the more prosaic titles like ‘Nautical Jargon’ and ‘Words From Aviation’, and go straight to the more alluring ‘Literary Insults’ or ‘Forbidden Words’. But then you would have missed learning the origin of ‘pushing the envelope’ or ‘pipe down’. For the first, here is what the book says: This refers to the ‘flight envelope’, defined as the combination of speed, height, stress, and other aeronautical factors within the plane which can be safely operated. To go beyond that, or to push that envelope, is risky and dangerous in aviation, but in its figurative sense, it means ‘to go beyond established limit’ or ‘to pioneer’, and is used in admiration rather than admonition.

‘Pipe down’ comes from shipping. A pipe was blown to assemble a ship’s crew for a difficult manoeuvre, and when it was finished the boatswain’s pipe was again sounded, with the command to ‘pipe down’. Back to the essay ‘Literary Insults’, it does live up to its name. “Thou art a base, proud, shallow, beggarly, three-suited, hundred-pound, filthy worsted-stocking knave; a lily-livered, action-taking, whoreson, glass-gazing, superserviceable, finical rogue; one-drunk-inheriting slave.” No, this is not Captain Haddock after three bottles of rum, it’s from the quill of none other than the great bard. Kent goes on this diatribe against Oswald in Act 2 of King Lear, perhaps the best example of a literary insult.

But Tintin fans won’t be disappointed—there is a separate essay on Captain Haddock’s expletives. Tintin’s creator Hergé faced this interesting problem with his character, the pugnacious, rum-guzzling, irascible Captain Haddock. Hergé couldn’t make him say swear words as it was a children’s comic book. He came up with this idea of Haddock cursing in obscure and esoteric words such as anacoluthon, cercopithecus, ectomorph and pyrographer. Talking of obscure words and definitions, if you ever wondered what pleonasms, dysphemism, aptagrams, anaphora, bacronyms, eponyms, eggcorns, paraprosdokians, spoonerisms, kennings and zeugma are in the English language, this is the book to grab.

But I was intrigued that while on saudade and toska in the chapter ‘Words That Don’t Exist In English’, there is no mention of the Czech word litost, which too doesn’t have an equivalent in English. Litost is a feeling of terrible sadness, a longing for nothing in particular, a despairing so strong it makes us tear up, it chokes us. “It is a special sorrow, a state of torment caused by a sudden insight into one’s own miserable self,” as Czech-French novelist Milan Kundera described it. Another such word is the Turkish hüzün, which novelist Orhan Pamuk puts like this: “Hüzün, which denotes a melancholy that is communal rather than private. Offering no clarity, veiling reality instead, hüzün brings us comfort, softening the view like the condensation on a window when a teakettle has been spouting steam on a winter’s day.” Then there is our own from the salubrious Konkan coast: susegad. It’s a relaxed, unhurried, low-strung attitude towards life, a knowing that however desperately we try, things will happen the way they do, like in susegad’s own country, Goa. Or are these words hidden elsewhere in the many pages of the book?

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Another miss in the ‘Language of Elections’ is the Indian invention: anti-incumbency. The term is not used for Joe Biden or Kamala Harris, for Jair Bolsonaro or Rishi Sunak, but only for a hapless Manmohan Singh, Jagan Reddy, K Chandrashekhar Rao, Basavaraj Bommai or Ashok Gehlot, which means the fact that a politician has governed (or misgoverned) a state or the country for a full term goes against his or her getting elected again. But these are just some quibbles, the book is great fun, full of surprises and insights. Let me leave you with a few lines from the delightful chapter on puns. “When she saw her first strands of grey hair she thought she’d dye. But then it grew on her.” And “Those who get too big for their pants will be totally exposed in the end.”