There is a widespread belief that living saints are given some intimation of their own mortality. Mahatma Gandhi often talked about living to 125 years or more, like some Hindu seers had done, but on January 29, a day before his assassination, Gandhi was unusually eloquent about mortality and his own death. On that day, members of the Nehru family had arrived at Birla Bhavan around lunchtime. They included Krishna Hutheesing, Jawaharlal’s sister, his daughter Indira with her four-year-old son, Rajiv, as well as Sarojini Naidu, the nationalist leader. They headed straight for the garden where Gandhi was basking in the sun wearing a Noakhali hat. Looking up at the approaching group, all wearing bright coloured saris, he greeted them, saying: “So, the princesses have come to see me.” In winter, Gandhi liked to enjoy his frugal lunch, mashed fruits and goat’s milk, in the open garden at Birla Bhavan, where he always stayed when in the capital and where he held his daily evening prayer meetings. Recalls Nehru’s sister, Krishna Hutheesing: “Gandhi looked exceedingly well that day; his bare brown body was absolutely glowing. This was because, even during his fasts, he took very good care of himself; for he had high blood pressure and used to have mud packs on his head and an oil massage to keep his strength up.... We sat in the sunshine talking. He teased me about my lecture tour, asked about my husband Raja and the children and we gossiped, nothing serious, just gay, idle family chatter.” Rajiv picked up some flowers that visitors had brought for the Mahatma, and started placing them around Gandhi’s feet at which Gandhi playfully pulled the young boy’s ear, and said, “You must not do that. One only puts flowers around dead people’s feet.”

An hour later, Margaret Bourke-White, the famous American photographer for Life magazine, arrived for an interview. It would turn out to be the last he gave. One of the questions she asked was: “Do you stick to your desire to live to the age of 125 years?” to which Gandhi replied “I have lost that hope because of the terrible happenings in the world. I don’t want to live in darkness.” She was followed by a group of villagers from Bannu who had been involved in a communal attack and rendered homeless. One agitated member of the group shouted at Gandhi: “You have done enough harm. You have ruined us utterly. Leave us alone and take your abode in the Himalayas.” That evening, while walking to his prayer meeting he confided to his grand-niece Manuben: “The pitiful cries of these people is like the voice of God. Take this as a death warrant for you and me.” While speaking at the prayer meeting, the angry words of the refugee was still playing on his mind. He declared: “I have become what I have become at the bidding of God. God will do what he wills. He may take me away. I shall not find peace in the Himalayas. I want to find peace in the midst of turmoil or I want to die in the turmoil.” Again, before going to bed, he repeated this thought to his long-term associate Brij Krishna Chandiwala: “You should take that as a notice served on me.”

Finally, there was this; an uncharacteristic outburst of anger at having to take some penicillin pills that his doctor had left for him to cure a bad cough he had developed. “If I were to die of disease or even a pimple, you must shout to the world from the house tops, that I was a false Mahatma. Then my soul, wherever it may be, will rest in peace. But if an explosion took place or somebody shot at me and I received his bullets on my bare chest, without a sigh and with Rama’s name on my lips, only then you should say I was a true Mahatma.” If this was a premonition, it was so eerily accurate as to be almost prophetic. Just a few hours earlier, Manuben, one of his “walking sticks” as he called her, had excused herself to go and look for powdered cloves that Gandhi took with jaggery to relieve his cough. Gandhi. who did not like his routine to be disturbed, remarked: “Who knows what is going to happen before nightfall or even whether I shall be alive?” Then, at 4 pm on January 30, his last day on earth, two leaders from his home state, Kathiawar, had arrived unannounced while Gandhi was in a crucial meeting with Sardar Patel. On being informed of their desire to see him, Gandhi said, “Tell them that I will see them, but only after the prayer meeting and that too if I am alive.”

Gandhi was approaching his 80th year, and was frail and unwell, having just ended one of his famous fasts, and the communal killings and ongoing tension had taxed him to the limit. On January 30, Gandhi had awoken at 3:30 am, unusually disturbed with the ‘darkness’ that had surrounded him, not just the killings but also the infighting in the Congress that he had helped build, with the growing chasm between Nehru and Sardar Patel. There was even a growing chorus for the Mahatma to withdraw to the Himalayas rather than face the post-Partition paroxysms and hostility from right-wing elements who were angered by his secular stand, especially what they saw as a soft line on Pakistan. He, however, knew that this was when India needed him the most. He had a long and busy day ahead. It would also be his last and it is possible he realised how much he still had to achieve. At 3:45 am, he surprisingly asked for a rendition of a Gujarati bhajan: “Thake na thake chhatayen hon/Manavi na leje visramo,Ne jhoojhaje ekal bayen/Ho manavi, na leje visramo (Whether tired or not, O man do not take rest, stop not, your struggle, if single-handed, continues.)” Shortly after, he started to work on revising the draft constitution for the reorganisation of the Congress party which he had started work on the previous night. It would be, in a sense, his last will and testament, his vision for the nation. It would also be the last thing he wrote.

Photograph by Getty Images, From Outlook 03 February 2014

Ominously enough, as Gandhi was writing his treatise on the Congress, Nathuram Godse was also finishing the last thing he would ever write, his own last will and testament. The letter was addressed to his co-conspirator, Narayan Apte, and stated, “My mental condition is inflamed in the extreme, so that it has become impossible to find out any reliable way out of the political atmosphere. I have therefore decided for myself to adopt a last and extreme step. You will of course know it in a day or two. I have decided to do what I want without depending on anyone else.” Gandhi’s military-like routine made it easier for him to carry out “the extreme step”.

On January 30, Gandhi woke early, as was customary for morning prayers which was held in the verandah outside his bedroom where he used to sleep with his inner circle, Manu and grand niece Abha, his two ‘walking sticks’, and Brij Krishna Chandiwala. Feeling unwell from the after-effects of his recent fast, Gandhi walked with the help of Manu and Abha to the inner room where he was given lemon and honey soaked in hot water followed by a 16 oz glass of sweet lime juice. After about an hour, he fell asleep, unusual for him. He awoke before 7 am to receive Mrs Rajan Nehru, wife of Jawaharlal’s nephew, R.K. Nehru, who was leaving for America that day. Normally, Gandhi would take a brisk walk outdoors before settling down to receive visitors and work on his papers but being under the weather, he did not feel well enough to perform his outdoor morning exercise.

At 8 am, it was time for his morning massage, during which he made some last minute corrections to the draft of the new constitution for the Congress before handing it over to his trusted secretary, Pyarelal, to give it a final look before forwarding it to the party headquarters. Then it was time for his daily Bengali lessons, both written and spoken, which he took from his grandniece Abha Gandhi. Having learnt nine different Indian languages, both written and spoken, Gandhi was determined to master Bengali. This day, his last day on earth, he did not deviate much from the routine he had set for himself. His morning bath was accompanied by a check on his weight, which, that morning, was 109.5 lbs. Those in the inner circle remember that last day vividly, perhaps because of the tragedy that it would end in, and they recall that the bath seemed to have refreshed Gandhi and given him greater energy, having been so ill and tired-looking for the past few days. He even showed a healthy appetite for breakfast, which consisted of exactly 12 ounces of goat’s milk, a cup of boiled vegetables with radishes and ripe tomatoes, as well as a glass each of orange and carrot juice. This was usually followed by a medicinal concoction of ginger, sour lime and aloe vera.

Photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum

After resting for a while, Gandhi got up on his own and started to walk towards the bathroom. It was a strange sight for Manu who said, “Bapu, how strange you look?” a reference to the fact that he had not gone anywhere recently without his ‘walking sticks’. Gandhi responded, quoting Rabindranath Tagore: “Ekla chalo, ekla chalo (Walk alone, walk alone)”. The last lonely walk he would take had begun. Gandhi had his usual mudpack at 1:30 in the afternoon and soon after received the well-known French photographer Henri Cartier Bresson who had come with an album of his photographs as a present. His last but possibly the most important meeting of the day was with Sardar Patel, which started, as scheduled, at 4 pm. Patel came with his daughter Maniben who doubled as his personal secretary. Although the meeting was to sort out differences between Nehru and Patel, Gandhi started the conversation with the affairs of Kathiawar, his own home state, where his father Karamchand had once served as dewan.

Gandhi and Patel shared a very close, warm relationship based on mutual respect. Both had sacrificed much for the sake of independence but they also had their differences. Only a few days earlier, Patel had spoken to Gandhi in harsh and bitter tones on the issue of transferring `55 crore to Pakistan. Gandhi was so distraught that he broke down and cried. Despite the opposition from stalwarts like Patel, the Union cabinet later passed a resolution to transfer the money, under pressure from Gandhi, a decision that had so angered Patel that he had offered to resign. At their last meeting on January 30, neither of the two had any inkling that an hour later, Gandhi would be breathing his last. The meeting was an attempt to repair damaged relationships, between Nehru and Patel but also between Patel and Gandhi. Just a few days earlier, Gandhi had counselled Patel and Nehru that one of them should withdraw from the cabinet for it to function smoothly. Later, he realised that the country needed the political wisdom of both Nehru and Patel, a view shared by the last viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, who had requested Gandhi to try and persuade Patel to continue to work together with Nehru for the sake of the country.

As was his style, Gandhi continued to use his spinning wheel while talking to Patel. He informed Patel that he would highlight the issue of unity in his post-prayer speech and also told him that he was meeting Nehru and Azad to discuss the issue after the prayer meeting that evening. He declared that he would not leave Delhi until the matter of unity between Nehru and Patel was settled. While Patel was still with him, Gandhi had his last meal, 14 ounces of goat’s milk, a similar amount of vegetable soup and three oranges. It was now 4:30 pm and the issue was still unresolved. It was agreed that the three of them would meet the next day. He had still not left for his prayer meeting which started punctually at 5 pm. Gandhi hated to be late for anything. It was close to 5 pm but the discussion with Patel had become so intense that no one dare disturb the two. Abha and Manu, as also Maniben, Patel’s daughter, were getting uncomfortable at the delay. Abha, in desperation, picked up Gandhi’s pocket watch and tried to show it to him but so engrossed were the two that nothing registered. Finally, Manibehn plucked up her courage and interrupted them. “It’s ten past five,” she announced. “I must tear myself away,” was how Gandhi bade his final goodbye to Patel. Those would be his last words, apart from that which escaped his lips before he breathed his last, a few minutes later.

Photograph by Getty Images, From Outlook 03 February 2014

Since he was running late Gandhi took a short cut, walked briskly, faster than normal, to the waiting crowd and assassin. Standing in front, wearing a military-style khaki dress, was Godse who greeted Gandhi with folded hands, hands that had a Beretta automatic pistol hidden between the palms. Gandhi returned his greetings and that would be his last act on earth. Godse fired three bullets into Gandhi, who fell with folded hands and “Hey Ram” on his lips. His body crumpled and Manu held him up in her lap. While some around him froze, others ran in panic. The enormity of the incident had still to sink in on anyone, except for Godse. The assassin did not try to flee. In the melee, no one had really noticed the man who had fired the fatal shots. One man who did was Herbert ‘Tom’ Reiner Jr, a diplomat who had just joined the US Foreign Service. New Delhi was his first posting and, after arriving, he wrote to his mother, expressing his wish to meet Gandhi and attend one of his prayer meetings. On January 30, he left the embassy and arrived at Birla Bhavan, to hear Gandhi speak. He was standing in the front row when Godse brushed past him and fired the fatal shots. Reiner immediately seized Godse and held him till the police arrived. Reiner would later recount his actions: “People were standing as though paralysed. I moved around them, grasped his (Godse’s) shoulders, and spun him around, then took a firmer grip of his shoulders.” Most newspaper and wire reports on the assassination merely referred to ‘an American diplomat’ and Reiner’s name only appeared in some American newspapers at the time.

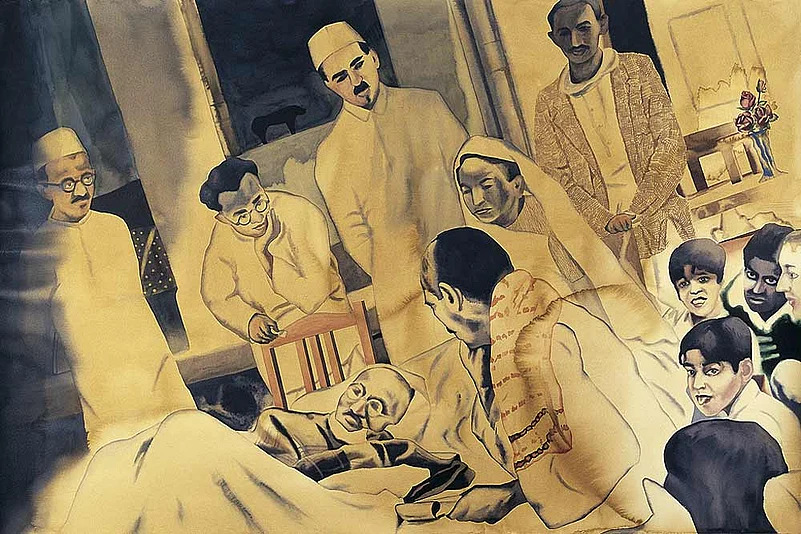

Even as Godse was being apprehended, Gandhi’s blood was spreading across the white shawl, made of Australian wool but spun by him. The pocket watch that he wore was shattered. It stood frozen at 5:17. His closest aides, Manu, Abha, Chandiwala and Pyarelal were in complete shock. A young lady doctor from Lady Harding Medical College, a close friend of Dr Sushila Nayar, Pyarelal’s sister, took over and placed Gandhi’s head on her lap. The body was quivering and still warm, the eyes half shut. She did not have the courage to announce his death, but she could tell he was no more. The news of the assassination spread like wildfire. Patel, who had barely reached his home after meeting Gandhi, rushed back to Birla Bhavan with his daughter. He took Gandhi’s wrist, hoping to find some sign of life. Finally, it was left to Dr B.P. Bhargava, a close friend of Gandhi’s aides present at the prayer meeting, to pronounce that Gandhi had been “dead for 10 minutes”.

The women gathered burst out wailing and weeping, grown men cried aloud. Patel stood ashen, unable to take in the enormity of the tragedy. Later, he would say: “Others could weep and find relief from their grief in tears, I could not do that. But it reduced my brain to pulp.” Maniben, his daughter, composed herself and asked the girls to join her in reciting the Gita. The sound of “Patita pavan Sita Ram...” rang out, punctuated by wails, as the crowds started swelling. Devdas arrived with his youngest son Gopal. He took his father’s hand in his and bending his head next to Gandhi’s ears he cried, “Bapu, say something.” The wailing had become uncontrollable. Next to arrive was Nehru, who buried his face into the blood-soaked clothes and cried like a baby. Patel tried to console him, patting his back. Nehru embraced Patel and sobbed uncontrollably. It was an unusual sight. The country’s prime minister and home minister acting like sons who had lost a beloved father. Lord Mountbatten was next to arrive. With thousands clogging the gates of Birla Bhavan, he could barely find a way to get in. “It was a Muslim who murdered him,” shouted an angry young man. “You fool,” retorted Mountbatten with his usual presence of mind, “it was a Hindu”, for he knew that if it was indeed a Muslim, the country would witness another bloodbath, this time of unimaginable magnitude. Only later did he get to know that it was a Brahmin who had killed Gandhi.

Photograph by Corbis, From Outlook 03 February 2014

Seeing Nehru and Patel in complete shock and grief, Mountbatten quickly took charge of the situation. Taking Nehru by the hand, he took him to Patel and whispered that Gandhi’s last request to him was to bring the two of them together. Almost instantly the two stalwarts broke down and embraced each other again. Grief had repaired what endless negotiations and go-betweens had failed to do. Gandhi had planned this reunion for the next day but had not lived to see it happen. That evening both Nehru and Patel addressed the nation over All India Radio. “The light has gone out of our lives...” said Nehru, in a phrase that would become interspersed forever with Gandhi’s death. A distraught Patel, generally a man of few words, managed to say: “My heart is aching...my tongue is tied...the occasion demands not anger but earnest heart searching from us....”

Someone suggested that Gandhi’s body be embalmed and kept in state for national and international dignitaries to pay their final homage. However, Pyarelal made it known that Gandhi was against this and had categorically told him “even in my death, I will chide you if you fail in your duty”. After much deliberation, Gandhi’s body was taken to the first floor balcony for his countrymen to have a final ‘darshan’ of their departed leader. At one point, distraught and completely lost, Nehru mentioned to Manu, “Let’s go and ask Bapu what arrangements must be made....” Everyone present burst into tears. At about 2 am, Gandhi’s body was brought down and given the last ritualistic bath by the family with water brought from the river Jamuna. As Devdas removed Gandhi’s clothes one by one, those present could see three clear bullet marks, the first one on the right side of the abdomen two and half inches above the navel, the second, an inch to the right and the third, the most fatal one, had made a hole an inch above the right nipple. The first two bullets pierced the frail body and came out of the back. While bathing the body, these two bullets were found lodged in the shawl. The third one was embedded in the lungs. It was found 27 hours later, when the ashes were being gathered from the cold pyre.

Emotions continued to run high as the group cleaned the blood from the body to prepare it for the final journey. The rosary that had fallen from Manu’s hand when Gandhi was shot was placed around his neck and so was a special garland made of handspun khadi. A red tilak was put on the forehead and sandalwood paste applied all over his body. Using flowers and leaves, the words ‘Hey Ram’ was fashioned near his head and ‘Om’ near his feet. His body was covered with a white khadi cloth, possibly spun by Gandhi himself. The body was then covered with flowers and rose petals, except for the chest. “I asked for the chest to be left bare. No soldier ever had a finer chest than Bapu’s,” said Devdas. The room was soon filled with the fragrance of flowers, smoke from the incense sticks and the sound of Gandhi’s favourite hymns. At one point, Nehru came to Manu and said, “Sing louder...who knows Bapu may wake up.” By now, thousands of people had surged towards Birla Bhavan, in the heart of Lutyens Delhi, to have a last darshan of their beloved Bapu. The body was once again placed on the balcony for them to view. It was brought down the next morning, draped in newly independent India’s tricolor, and placed on a gun carriage decorated with flowers. Two hundred hand-picked men from the Indian army, navy and air force pulled the vehicle manually, with ropes. Nehru, Patel and close family members sat next to the dead body.

Gandhi would often say that “Death is a celebration...death is God’s eternal blessing. The body falls and the bird within it flies away. So long as the bird does not die, the question of grief should not arise.” As the funeral pyre was lit and the world mourned the passing of the Apostle of Peace, the bird within was released into eternity.