The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute has been an important part of Poona’surban culture for almost a century, and certainly a hub of national and international scholarly activitythroughout the post-colonial history of India. To see, today, its ravaged book-stacks and decimatedcard-catalogues, its walls bare of portraits and the glass on its cupboards shattered, its ancient manuscriptsin tatters and its elderly denizens in shock, is first and foremost to stare intolerance in its ugly face. Inno civilized society in the world, in no time from the deep past to the twentieth century, has a vandalizedlibrary ever boded well for a people. When centers of learning and repositories of knowledge become the sitesof political violence, citizens must sit up, take note and take a stand. Some were prescient enough to knowthat this day was coming to us years ago, when Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses was banned. When the BabriMasjid came down, the writing was on the wall. When the shooting of Deepa Mehta’s proposed film on thewidows of Banaras, Water, was forcibly stopped, alarm bells rang loud and clear. With the storming of BORI byhooligans, the monster of fascism no longer growls at the gate – it has crossed the threshold, into thehouse that Gandhi built.

The public in Poona, in Bombay and in the rest of the country, knows it is witnessinga sign of some sort – an event that points to not one but several realities – but is utterly confusedabout which way to look, and what to look at. Where are we to turn our attention, as vanloads of policemenoccupy the premises of a decrepit old building that houses an irreplaceable archive of research materialrecently attacked by a mob? Is this about the protocols of academic writing? Is it about standards inpublishing? Is it about the legalities of authorial rights and constraints? Is it about historical truth? Isit about community pride? Is it about the regional politics between Brahmins, Marathas and other castes? Is itabout Maharashtra’s peculiar electoral arithmetic, whose equations are being worked out between theCongress, the NCP, the Shiv Sena, the BJP, the NDA and other players? Is it about India’s national honor andWestern neo-orientalism? Is it about the delicate relationship between cultural sensitivity and scholarlypractice? Is it about the freedom of speech? Is it about the responsibility of the state to maintain law andorder, and to protect its citizens and their public as well as private property? Which of this welter ofproblems thrown up by the ravaging of the Bhandarkar Institute, are we forced to address first and foremost?

My suspicion is that the most critical question is in fact the one that, as DilipSimeon points out again and again, almost no one seems to be raising. And this is – are we prepared todefend acts of violence perpetrated in the name of our identity, our beliefs and finally, our sentiments? Thework on Shivaji by the American professor James Laine must be judged on the cogency of its arguments and thepropriety of its methodology. Instead we are asked to judge it on the basis of the nationality of its author.Oxford University Press, Laine’s publisher, must be judged for the quality of the book it has put out, notfor the feelings its publication may arouse in some individuals or communities. BORI must be judged for itsability to maintain, or conversely its tendency to mismanage, the precious texts old and new that are in itscare, not for the caste of its fellows, administrators and employees, or for the color of the skin of thosewho use its bibliographic holdings. A claim about Shivaji’s parentage, made by anyone and put into thepublic domain, should be judged for the degree to which it is or isn’t grounded in empirically verifiablehistorical sources, not for its emotional effect on those who might cling to baseless myths about the greatking’s antecedents. The Sambhaji Brigade and the Maratha Seva Sangh, as political forces, must be judged forthe extent to which they respect or disregard democratic norms in building, mobilizing and representing publicopinion.

Let us say, for argument’s sake, that Laine’s scholarship is mediocre, or evendownright irresponsible. Let us say OUP’s editorial procedures, in this case, are not up to the mark; thatBORI is a bastion of upper-caste and foreign scholars, and that any conceivable doubt about who sired Shivajihas long been settled in favor of his mother Jijabai’s lawfully wedded husband, Shahji. Let us say Marathas,like any group, have every right to choose their preferred symbol and assert its sanctity and centrality tothem. But does any of this justify barging into the Bhandarkar Institute before it opens for the day,terrorizing the skeletal staff on duty, breaking furniture, and tearing up fragile books and pricelessmanuscripts? In this country there are constitutional instruments equally available to all, should differentactors in a dispute want to make claims and counter-claims about what is true and what is false in history. Inrecent memory, the blasting of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan and the looting of the Baghdad Museum inIraq ought to serve as reminders of where we do not want Indian cultural, social and political life to end up,right before our bewildered or blind eyes.

This is not to say that there is, to borrow the terminology of a letter of protestrecently signed by scholars across the world, a "centuries-old tradition in India of social and intellectualtolerance" that needs to be protected (The Indian Express, Pune: January 15, 2004, p. 3). In reality,tolerance is always yet to be constructed in our national life. It should not be assumed to exist, and thenits erosion lamented. Tolerance is the sum total of an infinite number of acts that must be performed inresponse to new interventions in the public sphere, not a default state of affairs disrupted now and again bysurprising – the preferred adjective among liberals is "shocking" – acts of intolerance.

Let us look back over the past three decades, roughly the entire period post-Emergency. Let us think for amoment of the trans-national (Bangladeshi / Bengali) novelist Taslima Nasreen, the critic Nancy Adajania andthe painter M. F. Hussain from Bombay, and the slain theater activist from Delhi, Safdar Hashmi. The personal,sometimes fatal, experiences of these persons, and the fate of the writings, artifacts and projects that theyattempted to put into the public domain ought to make it clear that the climate of political opinion andpractice enveloping us is not a tolerant one.

The fact that all of these individuals belong(ed) to minority communities or, in one case, are not even Indian by nationality, is even more alarming. When we assert the right of Indian citizens (aswell as of those who are not literally citizens but nonetheless contribute actively to the social and culturallife of this nation), to work in this country without fear or favor, we cannot make our assertion on the basisof an assumed atmosphere of tolerance that would be disturbed if such a right were violated. Rather, we haveto make the argument that if people want to live, they must let others live, and letting live takes as muchdoing as living itself.

We are quick to recall universities that went up in smoke, and the sacked temples,and the desecrated monasteries, and other instances of violence in the realms of culture and religion thatstand out in the long and turbulent history of the subcontinent. Nowadays the majority community, especially,has developed an extra-sharp historical memory, never mind that it is only sometimes accurate, and oftenentirely erroneous. Nalanda and Somanatha, Lhasa and Devagiri – how these names from our own strife-torn pastor from that of a neighboring region burn our purportedly democratized blood! But pre-modern polities neverclaimed to be tolerant. Nor do totalitarian modern states of any ilk. Free India precisely makes the claim tofreedom of expression. And this freedom wasn’t won for once and for all in 1947. It has to be fought foreveryday, and won – or lost – again and again. Our relationship to the ideal of tolerance has to be thatof Gandhian doggedness. After all, like other democratic values, tolerance is something that we can approachasymptotically through innumerable big and small acts of striving, but perhaps never really arrive at.

As Arundhati Roy said, using the present continuous, in her speech at the opening of the World Social Forum (Goregaon,Mumbai, January 16, 2004), we are at war. Ironic as it may seem, we must do battle – a satyagraha, if youwill – to iteratively achieve as close an approximation of a tolerant society as is humanly possible.

Speaking of reiteration, the spokesperson of the Sambhaji Brigade, one ShreemantKokate, was quoted in the press as saying: "Even if BORI is burnt ten thousand times the insult inflictedupon Jijabai would not be mitigated" (The Indian Express, Pune: January 10, 2004, p 1). Mr. Kokate isabsolutely right. Gestures of insult and complaints of injury will not cease after one violent incident, oncethe supposedly injured parties have got their own back, as it were. But someone should ask him, just forlogical clarity: if a library is burnt down to the ground once, how could it be burnt again, leave aside10,000 times over? What does it mean to even contemplate this kind of destruction after destruction? I suspectfor all their seeming irrationality, Mr. Kokate and his brethren recognize that for them to carry on existing,they have to figure their enemy as a rakt-beej rakshas, a self-renewing demon. That way they can beperpetually occupied, decapitating unendingly a demonic entity whose clones spring up from every spot on theground where a drop of blood from its severed head has fallen. In a sense, to them, the Bhandarkar Institute is indestructible.

Forms of self-expression, more or lesscreative and aesthetic, more or less dissenting and critical, will come up all the time in a living culture,regardless of the nature of the state, and regardless of the might of the forces of oppression and repression.Attacking a given institution or individual might address, in this case for the militant Marathas, aparticular sore-point, but it will not take away the feeling of outrage and the stance of victimization thatfascists repeatedly and routinely use as the drivers of all their political actions. If we buy into them,these can lead to no place – promises about the revival of golden pasts or the creation of utopian futuresnotwithstanding – other than the end-point of national self-destruction.

In the public debate that has ensued in the weeks since January 05 (the day BORI was sacked), many people,while condemning the attack on a venerable scholarly institution, have accused the liberal intelligentsia –or what’s left of it – as well as the secularist sections of the press – minute though they are now, inthe Indian mediascape – of expressing concern only at certain kinds of attempts to undermine civilliberties, namely, those that come from the political right. What about the violence that groups on thefar-left have done and continue to do with impunity in different parts of the country? How come no one in theEnglish-language establishment cries foul when Naxalites and Maoists kill humans and destroy property in thename of their ideologies of social transformation or total revolution? This is an entirely fair question.

In response, it can only be said that in the regnant climate of communalism andfascism, we have to be as alert to cultural policing and intimidation tactics that emanate from the left as weare to those that come from the Sangh Parivar and its allies. And what of the left or right, today evensupposedly centrist political parties will allow themselves to be strong-armed and held to ransom byextremists of every stripe. The real losers in all these scenarios are the citizens of India, who find thefragile space of their freedom shrinking day by day. We have no choice but to evaluate afresh exactly wheredifferent claimants to power stand on violence, regardless of their histories of being pacifist orprogressive. A Congress or Communist-ruled state in this country is not automatically pro-people; it is nosafer a haven for artists and intellectuals, nor is it a stronger guarantor of the democratic rights of thecitizenry, than a state ruled by the Hindu Right. We should not harbor any illusions about the ubiquity of thethreat to the liberty, equality and justice that were promised to all in the Constitution. The forthcominggeneral elections will surely make quite clear to us how fast our options are shrinking, if we seek a realalternative to either soft or hard fascist tendencies in our polity.

It is our prerogative as well as our responsibility, as citizens of this contemporaryIndia (and not a mythical long-suffering and ever-tolerant India), to reject the odious politics of sentimentand offense, and the violence it entails in our public life. The deplorable sight of toppled book-racks andbroken book-cases, of police uniforms and batons on a scholarly campus, has to be seen to be believed. ThePoona press keeps predicting that BORI will be back on its feet very soon, but this is baseless optimism. Itwill in fact take months if not years to properly assess the extent of the damage done to the holdings ofPoona’s most famous manuscript archive and Indological library. However, it should take us no time at all tounderstand the enormity of the blow to Indian democracy represented by the attack on the Bhandarkar OrientalResearch Institute, and the banning by the Maharashtra government of Jim Laine’s book on Shivaji.

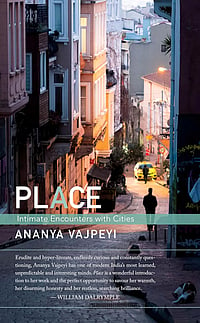

Rhodes Scholar Ananya Vajpeyi is at the University of Chicago, in the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations.