Empowering women with driving skills and livelihood

Wheels of Sustainability

BRIDGESTONE

Adopting a strategic and multidimensional approach, Bridgestone India

has rolled out

initiatives to leave a long-term positive impact on communities and the

environment

A leading tyre manufacturer, Bridgestone India is

committed to ‘Serving Society with Superior Quality’.

This mission statement is based on the Group founder

Shojiro Ishibashi’s belief that business must exist beyond profits

and positively contribute to its communities. In the last nine

decades, the corporation has a global presence with over 163

production facilities across 26 countries. And the principle of

service with quality is seen in its CSR initiatives as well.

“Bridgestone’s CSR activities are driven by its global CSR commitment ‘Our Way to Serve’ and this is interwoven with the corporation’s mission statement. Through ‘Our Way to Serve’s priority areas of ‘Mobility’, ‘People’ and ‘Environment’, Bridgestone leverages its strengths and competencies—thousands of teammates worldwide, a global network, industry leadership and a history of innovation—to improve the way people move, live, work and play. We believe it is essential for us to prioritise our business operations along with our CSR focus, to ensure a wellrounded growth,” explains Parag Satpute, Managing Director.

The goal is inclusive growth through

interventions to improve

healthcare, promote education, generate livelihood opportunities

and support rural development. And the growth stems through

strategic partnerships with experts and employee volunteers.

Different projects need different solutions and partners are roped

in for their expertise. Volunteers are engaged in different ways in

the initiatives-in some projects they are engaged in hands-on

activities like imparting trainings, organising camps, assisting

CSR team and then there are exposure and engagement trips,”

further adds Ranu Kulshrestha, Head CSR.

“During the Sangli, Maharashtra

floods 2019, a team of

volunteers did a needs’ assessment of the region. Based on

this, we designed our long-term intervention related to

reconstruction of damaged schools. This visit also led to

active involvement in mobilisation and distribution of relief

material. During 2019, we could mobilise 4,348 volunteering

hours engaging 631 employee volunteers,” says Kulshrestha.

Simulator experience at IDTR, Pune

Commercial vehicles playing a crucial role in connectivity and logistics, the company considers the safety and health of truck drivers a high priority. A study conducted by Kantar IMRB in association with Castrol India in 2018 says that over 50 per cent of truck drivers in India suffer from health issues, ranging from minor to major afflictions owing to high working hours. So, the company works closely with this community and addresses critical issues such as training and skill development, soft skills and financial literacy, gender sensitisation and refractive error and vision correction. For this, Bridgestone India has two projects in place: Sarthi and Drishti.

Project Sarthi: Under this, Bridgestone India has partnered with Institute of Driving Training and Research (IDTR), Pune, for a 45-day residential training in HMV and LMV. The admission criterion is easy: the student should have passed class X, have a learner’s licence and pass the admission test. A batch of 40 students is fully sponsored by Bridgestone. For placement, the institute has a tie-up with various government bodies such as state transport authori - ties, Army, Tata Motors and some reputed travel agencies.

Simulator experience at IDTR, Pune

There are classroom and on-track trainings, experience simulators and technical orientation. Safe driving meas - ures are given importance. “Training is conducted by ex - perienced instructors to impart practical, systematic and scientific driver training,” says Rajeev Ghatole, principal, who has trained thousands of drivers in his 32-year-long career. Besides the technical training, there are knowledge sessions on first-aid, financial literacy, yoga, meditation, stress management and healthcare after 40. Initially, most of the enrolments were from Vidarbha and Marathawada regions of Maharashtra; however the programme’s popu - larity has brought in students from Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan as well. With most students in the age group of 22-34 years, word about Project Sarthi has spread through social media, brochures and recommendations by those who have benefited. Each person gets a government certi - fication which adds weight to his/her CV.

on-track training for driving HMV and LMV

Govind Kokare is satisfied that he now has a

regular job with Pune Mahanagar Parivahan Mahamandal Ltd, driving a city bus.

“I heard about this programme from a friend in my village.

Fortunately, I got admission and have a steady income now. With a

wife and a child and no income earlier, I felt so hopeless but this has

changed my life,” he says. In fact, he now runs a WhatsApp group for

job seekers, sharing all work-related information to many in search

of livelihood. Like Govind, many more have found work and hope.

Milind

Wakure, from Osmanabad, says, “This training is very expensive outside. It costs

close to Rs 60,000 at any private institute. And

then it’s not even as good as what we are taught here. I was searching

for a private job when a friend recommended this. He had also passed

out from here. The facilities are good, the trainers are good and I am

looking forward to a steady future.”

An instructor at IDTR, Tanaji Ramachandra Walunjkar says that some students are not even able to drive a car when they enroll for the programme. “We equip them to drive in all conditions—through fog, over curves, bumps, on mountain roads, at night. There are intricacies involved in reversing, parking, deep curves, through water. They are taught to understand traffic signs, which is why we admit students who have studied till class X.”

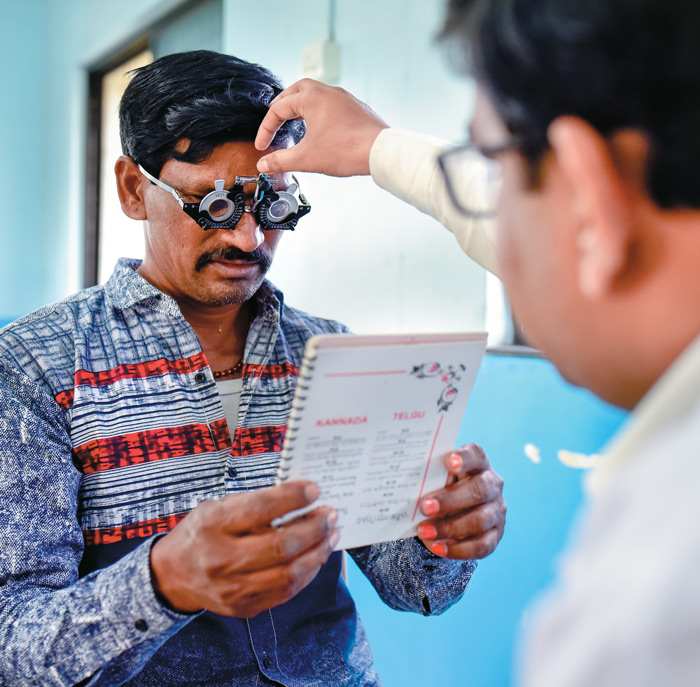

Checking vision under Project Drishti across the country

Pravin Chande came from Raigarh and was a

helper in a shop in Pune.

But is now looking forward to a good job with Tata Motors. Pankaj

Devare from Jalgoan used to do some marketing and daily labour. With

this 45-day training, he can now drive a Sumo, bus and dumper, and is

happy that his monthly earning will be a stable Rs 13,000-14,000.

In

addition to this, there are sessions on vehicle parts and two-day

sessions on tyres, maintenance and fuel saving at Bridgestone’s plant

in Chakan. Sarthi tyre management training and Swavlamban tyre

fitters training are undertaken by employee volunteers. Around 371

youth have been trained as skilled commercial drivers. The target is to

train 1,000 people by the end of 2020.

Parag Satpute

Managing Director, Bridgestone India

Project Drishti: “We don’t know where we will be tomorrow,” say the truckers sitting in a facility provided by Ultra Tech Cement plant, Solapur. “It all depends on where we have to take the goods.” Life on the road means an unhealthy diet and strenuous hours of driving, mostly at night. With about five million truckers plying on long routes across the country, road accidents are the largest cause of unnatural deaths. And through Project Drishti, Bridgestone addresses vision-related ailments.

This project promotes safe mobility by

organising health camps to

provide doorstep facilities for vision, blood pressure, sugar, eye pressure

check-ups. Truckers with any vision disorder are provided spectacles.

Critical patients are referred to the nearby base hospital for further

investigation, treatment and medication. “Volunteers help at these camps

with registration and counselling,” says Kulshrestha.

On the day of

screening, average 100-110 truckers are expected to

screen with visual acuity test, automated refraction, manual refraction,

general eye evaluation, colour vision test, Intraocular pressure. The

programme is in partnership with Mission for Vision, which brings in

medical expertise. Ophthalmologist Sagar Mohan Pawar works with H.V.

Desai hospital in Pune and was attending to patients at Solapur. “Besides

check-up, we also counsel them on health and how to take care of their

vision. For serious issues such as cataract, we help with surgery. We

recommend check-ups twice a year,” he says. “Initially, we tell them to

wear the glasses for two hours at home to get used to them.”

Both Rajkumar

Deshmukh and Gautam Gaikwad are in their 40s. They

have been driving trucks for over two decades now. “We find it difficult

to go to a specialist with our income and lifestyle. We are always on the

road and we come back to the same place after many days. As these camps

will be held all over India, we can avail the facility wherever we are,” say

the duo. Both of them have been experiencing eye problems and feel that

prevention is better than cure. Both have been recommended spectacles

and are waiting for their pair. Gaikwad has watery eyes and Deshmukh can’t see

things up close. Bridgestone India also gives a free first-aid kit

to the truckers on their first check-up. Each kit comprises of OTC medication

such as paracetamol, anti-septic lotion, ointment for pain, bandages etc.

Since the inception in July 2017, more than Rs 24.6 lakh has been spent

on this. Over 4,917 truckers have undergone vision check-ups and

treatment and 2,254 spectacles have been distributed. The project is

scalable and Bridgestone is always actively identifying more places

where the concentration of truckers is high and camps can be held.

practical training on the road

Focussing on sustainable livelihood, the company decided on a programme that would empower women, give them financial independence and inculcate the spirit of entrepreneurship. To achieve this, Bridgestone partnered with Mumbai-based all-women parcel delivery firm called Hey Deedee. The project, titled ‘Last Mile Delivery Girls’, involves training of women to become delivery agents for e-commerce sites. Empowering women is important as they in turn uplift the family and contribute to the country’s progress, is the underlining principle that defines this project.

Co-founder of Hey Deedee Revathi Roy with the girls who have been trained

Co-founder of Hey Deedee Revathi Roy, who

was a rally driver, feels

that the logistics sector lacked good delivery agents and driving instills

confidence in women. It also gives them regular and better income.

“All the girls are insured and taught the basics of self defence. Over the

last three years, I have seen their confidence levels change. We now

have a pool of good female drivers with us, who deliver on time and are

conscientious in their approach.”

Hey Deedee mobilises women from

low-income, Below Poverty Line

(BPL) backgrounds where the annual income is less than Rs 1 lakh.

They are given a 45-day to 90-day training for two-wheeler driving

In the village of Bukanwadi, Osmanabad, women participate in water budgeting

There is classroom training and simulator

experience ini

-

tially and then the girls are trained on the road. Besides this,

there are soft skills training in good hygiene and knowledge

of road safety measures. The organisation helps the girls

procure a licence and a vehicle at an attractive rate of inter

-

est. The girls are given a helmet, t-shirt and taught to wear

closed shoes. “There is 100 per cent placement--either with

the organisation doing an instant parcel delivery service or

with an e-commerce/food delivery platform requiring de

-

livery services,” says COO Uma Aiyer.

The girls are able to make at

least Rs 15,000 per month,

bringing them out of BPL. And they have an asset worth

Rs 60,000 in a two-wheeler for their professional work.

Talking about her transition, 42-year-old Manjusha

Virendra Mishra from Pune recounts how tough it was being

a single parent who did not have a good income. But working

with Hey Deedee has changed her life.

Seetha Laxmi is 35 and used to sell imitation jewellery but was unable to make ends meet. She has two children and with this job, she can now earn Rs 15,000-20,000, depending upon the season. “My husband had abandoned us but now I can send my children to school and take care of the house as well.” Over 200 girls have been trained under this project.

In the village of Bukanwadi, Osmanabad, women participate in water budgeting

With climate change, the planet is undergoing a massive environmental shift. And natural resources such as water are more precious than before. In Maharashtra, certain areas such as Marathawada are facing a severe drought situation since the last five years. More than 60 per cent blocks (180 out of 353 developmental blocks that is sub-districts) are water stressed. This is despite the fact that the state has more than 5,000 big dams for storage of surface water. As there are around two million irrigation wells, abstracting around 54 per cent of annually replenishable groundwater, access to sustained, equitable drinking water remains an issue.

In the village of Bukanwadi, Osmanabad, women participate in water budgeting

To address the needs of water-stressed

regions, Bridgestone

India has partnered with the United Nations Children’s Fund

(UNICEF) of India for project ‘Drops of Hope’. This project

highlights the importance of water conservation and drinking

water security throughout the year. The partnership has been

formed in collaboration with the Department of Water and

Sanitation, Government of Maharashtra.

The process began with a baseline

survey in three pilot

districts of Latur, Pune and Osmanabad. Statistics show that

only half of the rural households in Maharashtra have access

to tap water, and only 63 per cent is treated. Close to 20 percent of rural

households still depend on distant and unprotected sources

for their domestic water supply. Around 1/6th of rural population de

-

pends on public hand pumps. Per capita water supply in the state has

huge disparities.

The process of addressal begins with strengthening village level com - mittees to find local solutions to drinking water safety and security planning the year through. Bridgestone India provides support to UNICEF in undertaking training and skill development of community members and key officials at the village, block and district level to build water supply structures and ensure their proper maintenance. Another key aspect is the use of communication processes and tools to support positive behaviours towards water usage and management. “Awareness sessions on water budgeting have been held in our village,” says Mahadev Pandurang Chame, Gram Panchayat member of village Bukanwadi in Osmanabad district. “We are dependent on rain for water and this re - source can’t be created by humans. So, we realise that all of us have to do our bit.

There are approximately 318 families in our village. The main water resource is in the anganwadi. A big pump is there. The new water storage tank of 10,000 litre capacity has been constructed by the agen - cies. So, now we have four water storage facilities in this village. For op - erating bore wells, we are dependent on electricity which is also erratic in this part. So, with the new tank, we are able to get water at any time. Then we are also careful in how we use water at home—using only what is required for bathing and other household needs.”

At IDTR, Pune, practical training under Project Sarthi has helped many

With summer setting in, storage becomes a crucial aspect for close to three to four months. Each home in the village has a storage tank and there are soak pits in four homes. The village is waiting for funds from the government to make more soak pits. “We have been imparted knowledge on use of sprinklers as well, so now we use that for the fields. That way, we save a lot of water there too. So, with these interventions, we have had more water for an additional three months,” says Chame. UNICEF partnered with local agencies such as Gyan Prabodhini and ACWADAM for mobilising people on ground. The survey was done in Bukanwadi and the neighbouring Kawalewadi and Pardhi Pidi villages. Measures include construction of a storage tank in Bukanwadi, aware - ness sessions on water budgeting and agriculture methods, formation of committees, imparting solutions for clean water such as chlorination, regulation of water distribution through committees.

Surakha Tukaram is a member of the village

water and sanitation

committee in Bukanwadi. She is also a member of the village savings

bank group. “When the agencies came initially, they wanted to meet the

entire village. So they approached the gram panchayat, came to the

anganwadi, and saw the issues we are facing. As I am a supervisor with a

savings bank group, comprising 200 women, I requested the women to

come along for the meetings. Out of the 12 committee members, six are

women. Along with ASHA tai, we discussed our problems with the

agencies. With the new storage facility that has been built, we don’t have

to worry about what time to fill water or face the lack during an emer

-

gency,” she says.

Chaya Bhaskar Rao is a 45-year-old housewife living in

Bukanwadi. She

has a soak pit and multiple storage drums, including an underground

tank. But the entire storage comes to around 1,000 litres. And summers

are challenging, she reveals. “Water should be carefully used. We need to

save water collectively and not leave water storage facilities open. In our

village, we discuss ways to save water on a regular basis,” she says.

In

the long-term, the project aims to cover 17 over exploited watersheds

reaching out to nearly 3,25,000 people in 111 villages.

The road is long but

Bridgestone India continues to roll the wheels to

reduce social exclusion and increase economic and social capabilities

with a holistic approach