The energy backstage felt very different from what I had experienced during the shows I had done as a TV presenter. The green room door was pushed ajar and there was a rush of friends, strangers and visitors pulling at my hand to congratulate me. We were to start at 6.30 pm but the hall was packed with eager music lovers by 6 pm at the India Islamic Cultural Centre in Delhi. This was unexpected by Delhi standards where people can walk in fashionably late. We had no choice but to start early. I instructed my first set of performers to be ready 20 minutes before time, while I rushed on stage to calm the restless energy of my audience. I greeted them with an unprepared speech. I am used to unscripted speaking in my Live news studio, but this speech on stage was about my grand-uncle, Talat Mahmood, and had nothing to do with current affairs.

“We are all here for the love of Talat Mahmood. To celebrate his timelessness. Be it Dilip Kumar standing between fluttering curtains for ‘

’ or Sunil Dutt consoling Nutan over the phone with ‘Jalte hain jiske liye’, Talat Mahmood still pulls at heartstrings. We are all here for the love of his silken voice…” I said all of this and much more and quickly walked backstage. As I heard the applause to my speech at the first-ever concert I started in his memory, ‘Jashn-e-Talat,’ I wondered how often Talat Mahmood himself would have received such reception, show after show, year after year.

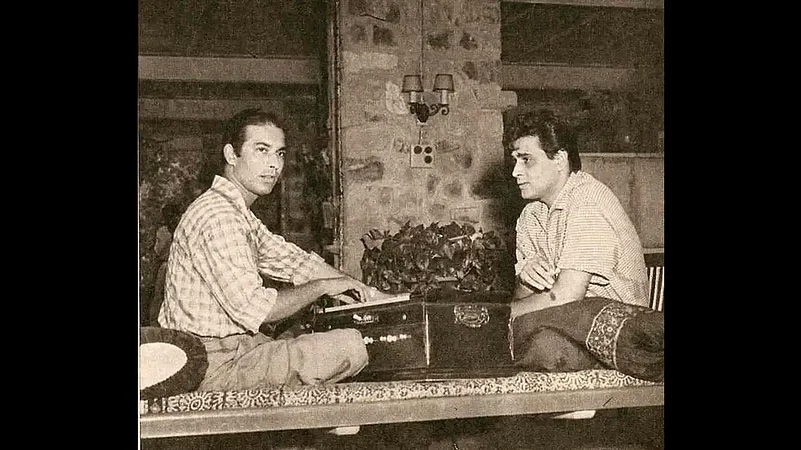

Talat Mahmood was one of the most popular singers of the Indian film industry, known for his soft velvety voice. As a significant part of the Golden Era of the Indian music film industry, he gave several memorable hits from the ‘40s to the ‘60s. He was the voice of Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand, Raj Kapoor and Sunil Dutt, to name a few. It is often said that Dilip Kumar’s phase of the Tragedy King would have been incomplete without Talat Mahmood’s voice in his songs. “Ae dil mujhe aisi jagah le chal” epitomised the lovelorn mood of Dilip Kumar’s films. Talat’s good looks and gentle mannerisms also had film directors casting him as the main ‘hero’ for a dozen films. He romanced Nutan, Mala Sinha, Suraiya, Shyama and Nadira as the main leads in films. Some of these films were hits, some weren’t.

Apart from his thriving film career, he had a parallel career in non-film ghazals since the 1940s and was fondly given the title of the ‘King of Ghazals’. He gave record-breaking sales to music labels and often experimented with the genre to add Western sounds of the guitar and drums. Amidst all this, he remained dedicated to the class of Urdu poetry and had the masses learn it through his finesse and appeal. It’s important to acknowledge that today’s Ghazal music industry across the Indian subcontinent rests on his shoulders with later legends such as Mehdi Hasan and Jagjit Singh choosing this genre of music only because they were die-hard Talat fans.

He was, once again, a pioneer, when it came to concert tours outside India. He started touring way back in the 1950s much before Indian stars from Bollywood did world tours in top locations such as Madison Square and the Royal Albert Hall. At the peak of his career, he did his first-ever tour to East Africa. That marked the start of an Indian playback singer doing world concerts and soon everyone else followed suit. While being interviewed at the Joe Franklin Show, he was introduced to the American audiences as the ‘Frank Sinatra of India’.

If we go back a bit further in time during pre-independent India, one realises that Talat was a rare artiste to be an equally big celebrity before 1947. A familiar voice on All India Radio, who sang ghazals to the poetry of Ghalib, Fayyaz Hashmi, etc. Soon after completing his music education in 1944 at the famous Bhatkhande School in Lucknow, a young 19-year-old Talat dashed to Calcutta upon being called by the then giant of the music industry Pankaj Mullick. In those days, the centre for film production and studios used to be in Calcutta. Talat was signed up by the New Theatres Studio. “Tasveer teri dil mera” was his first song recorded for Mullick. In the same year, Mullick decided that Talat’s voice should be used in Bengali songs as well. It was the genius of Talat to learn a brand new language and sing “Duti pkahi duti teere” and become a new sensation in Bengali songs. Thus started his career in Bengali music where he sang about 50 songs using the name Tapan Kumar, till he shifted to the upcoming film industry in Bombay.

I am beginning to discover fascinating aspects of his career while I’m currently in the process of writing his biography. Ironically, ever since I launched the Jashn-e-Talat concert series, I have started receiving a lot of his fan mail. I was informed by an admirer in Kerala about his song in Malayalam, “Kadaale neel kadaale” which topped a survey of all-time Malayalam hits. He was awarded the Best Marathi Singer award for his song “Yash hey amrit”. Effectively, what I’m trying to say is that Talat sang in more than 15 regional languages and managed to ace that too.

One can’t imagine a gentle and charming personality like Talat to be an activist. But he always believed in standing up for what’s right. In the 1960s, he took charge of the Playback Singers Association as the Secretary. The campaign for the right to royalty fees for playback singers was heating up. Talat led the way, along with his friends Mukesh and Lata Mangeshkar. It was the longest strike of singers that the film industry had seen for the cause. It was a moment when music labels and film producers could no longer look away from this demand. Once again, Talat left his indelible mark on an issue which has come a long way in helping give singers their right to royalty.

After a long and eventful career, the Padma Bhushan was conferred upon the singing sensation in 1992 by President Venkatraman. His film days were long over by the 1970s, but he spent the next two decades touring the world and singing for his fans.

Before I was bitten by the bug of doing the Jashn-e-Talat concerts, most of my friends and colleagues had known nothing about my connection with Talat Mahmood. I hadn’t spoken much about this and had certainly never written about it. Talat Mahmood was my grand-uncle, my naani’s (maternal grandmother’s) brother. My brother and I called him ‘Bambai Nana’ simply because he lived in Bombay.

When I was five years old, he took us to his friend Manna Dey’s house. We had also made a brief stop at my idol ‘Eetab Bashan’s’ (Amitabh Bachchan) house Jalsa, but alas he wasn’t home. When I met him when he came to receive his Padma Bhushan in 1992, he did a special performance for his fans. In a packed hall, the requests for songs wouldn’t stop, till he apologised that he couldn’t stretch the concert any further. In my teens, I realised how incredibly good-looking my ‘Bambai Nana’ was in his prime. While looking at old black and white family albums, his vibrant presence jumped out of those still pictures. But it was his warmth which I remember most.

It was painful to meet him just a year before his death on May 9, 1998. He was feeble and often lost in his own thoughts. Yet, he was always concerned if we had eaten our meals and Khalid, his son, took us around the city.

Today, ‘Jashn-e-Talat’ is a successful festival. With the unstinting support of my husband, we took it across big cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, and Lucknow; with multiple meetings with artists, sponsors and collaborators. It has now been marked by the British Council as one of the top festivals to attend in India. I had decided to make this a mould-breaking festival, just like his personality. It’s a multi-arts platform dedicated to his music, his films, his unparalleled contribution to ghazal gayaki and his pioneering efforts in introducing this genre to mainstream film music. The festival has painstakingly worked out a formula for involving the youth in his music. Many college-goers have sung his songs in our shows, as it opened up a new world of music to them. Many who didn’t sing, enjoyed dancing (believe it or not, hip-hop and salsa) to his vintage music in a flash mob organised by us. Today, we are fortunate to have stalwarts perform for us, such as Talat Aziz, Radhika Chopra, Kathak dancers Shovana Narayan, Vidha Lal, Raghuraj Bhatt, and actor Sohaila Kapur, who have all graciously lent their voices and hands and feet to my cause. There have been artists such as Amit Srivastava and Anubhav Som who have made LIVE portraits of Talat Mahmood on stage, adding yet another visual element to our concerts. Up until the pandemic, ‘Jashn-e-Talat’ created a record of doing one ground event every four months, across cities. This year, we will make a comeback in Pune.

Unfortunate as it is in this vitiated climate of our times where only a certain ideology reigns and would like to see the end of the Ganga-Jamuni flavour of our traditions, especially in our educational institutions, my request for hosting a Talat Mahmood concert at his alma mater was stonewalled by its Vice Chancellor, Shruti Sadolikar, in 2018. My multiple requests to accommodate an evening to commemorate Bhatkhande’s famous alumnus were rejected time and again. But I firmly believe that better sense would prevail in the days to come. Because both Talat Mahmood and Bhatkande University are national treasures that should be kept away from politics.

Talat Mahmood lives on….And so will Jashn-e-Talat, a celebration of the singer.

Sahar Zaman is a television news anchor and editor in national media. She is the Chief Curator of ‘Jashn-e-Talat’.