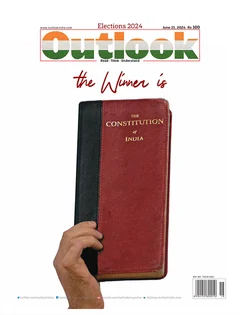

As the new National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government gets ready to take office, this might be an opportune moment to take a look at Indian democracy’s experience with coalition governments, which one might argue, are the only possible form compatible with Indian politics. After all, rarely in its history, over centuries, has India ever had one centralised power rule over it without having to adjust with regional satraps who remained crucial elements in the power structure.

Sometime around the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, Indian democracy entered what has been called the ‘era of coalitions’, saying goodbye to what political scientists described as the ‘one-party dominant system’, or the ‘Congress system’, to use Rajni Kothari’s expression. Since then, there have been several phases of coalition governments but the fundamental feature of a coalition involving RSS-linked parties is the control this organisation tries to wield over the entire coalition, as we will see.

Among the earliest expressions of this coming change was the emergence of the National Front (NF) government led by V P Singh of the Janata Dal that took office in November 1989. The NF, comprising parties like the Telugu Desam Party (TDP), Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), among others, formed the government at the Centre, interestingly, with the support of the Left on the one hand and the BJP on the other. This circumstance itself was an index of the way things were to change irreversibly in the coming decade. For the rapid dwindling of the space once occupied by the Congress was a consequence of the unravelling of the ‘rainbow coalition’ that the party itself had been, where all caste, regional and community groups, indeed all kinds of class interests as well, had found a place within it till about the end of the 1960s.

The unravelling of that coalition has to be read as a consequence of two developments that had started manifesting themselves in the decade of the 1980s, though their roots can be traced further back to 1967, when the Congress lost power in nine states for the first time.

First, against the backdrop of severe economic crisis, inflation, drought and consequent food shortages, frictions between different social groups started taking a political form. Perceptions of urban areas prospering at the cost of the villages and some regions benefiting at the cost of others lay behind the rise of the regional parties that eventually took the form of a full-fledged break with the ruling party.

Second, larger and abstract categories of representation like ‘nation’ or ‘class’ seemed to not sit well with the rise of regional aspirations, which was also linked with the rise of new regional vernacular elites that were at odds with the dominance of the older Westernised, Nehruvian custodians of Congress-style secular-nationalism.

Between the unravelling of the social coalitions within the Congress and the emergence of the NF and the beginning of the coalition era, lies the critical period of the Janata Party (JP) government that took power in the aftermath of the Emergency in 1977. This was a short-lived and largely failed experiment—except that it did, during its brief tenure, manage to undo some of the wrongs of the Emergency. The JP, in a way, tried to replicate the coalitional impulse within the party-form in the way the Congress had once embodied it. This was effected through the merger of parties as diverse as the Bharatiya Lok Dal, the Swatantra Party, the Socialists, Congress (O), Congress for Democracy and the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS). Unlike the Congress, however, which had evolved in a coalitional form over decades during the anticolonial struggle and continued after Independence, leaders of the JP seemed incapable of being able to think beyond their own ambitions and the immediate exigencies of power.

Nonetheless, it would be wrong to see the collapse of the Janata experiment simply as a result of the short-sightedness and bickering among the leaders. Key to a proper understanding of the collapse is the role played by the RSS and the leaders associated with its pre-JP political wing, the BJS. It was widely perceived that they systematically went about destabilising and toppling their own Janata governments where they were not the dominant force.

Rarely in its history has India ever had one centralised power rule over it without having to adjust with regional satraps who remained crucial in the power structure.

The socialists in the party had been repeatedly raising the demand that the BJS members renounce their ties with the RSS, which had been functioning as a party within the party. The perception was widespread that this bloc aimed to take control of the JP itself. In the event, the demand for an end to ‘dual membership’—that is, simultaneous membership of the RSS and of the JP—came to a head, leading eventually to a collapse of the Janata experiment.

This experience constitutes an important episode if we want to understand the relationship that the RSS and its political arm, the BJP, have had towards coalitions. Wherever the BJP exists, the RSS functions as the ‘extra-constitutional centre of power’—that is to say, regardless of the popular mandate that the BJP receives, it is finally accountable not to its electorate but to this organisation that is not accountable to any institution or forum. Further, the RSS—and therefore the BJP—espouses samarasta or cultural homogeneity as its ideal, which not only runs counter to the long and diverse history of the subcontinent, it is also inimical to any attempt to reconfigure power relations between the upper castes on the one hand, and the Dalits and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) on the other. It was, in fact, around the issue of 26 per cent reservation for OBCs introduced by Karpoori Thakur in early 1978 that one of the major conflicts between the socialist bloc and the RSS lobby had broken out in the JP.

The RSS fundamentally believes in the idea of ‘One Nation, One Culture’, which means that its project is to assimilate all the diverse cultural practices into one national culture. That is why the BJP repeatedly enters into a conflict with the southern states on the question of Hindi imposition—Hindi being its vehicle for achieving homogenisation.

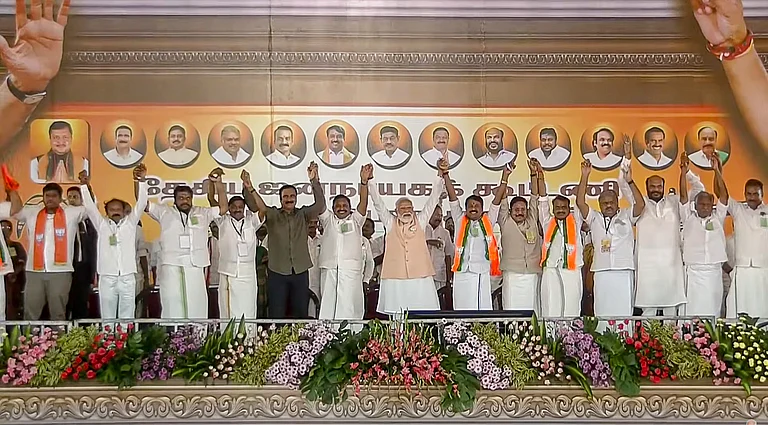

With the advent of Narendra Modi, an additional aspect has been added to the ‘One Nation, One Culture’ idea: that of One Leader. This fundamentally obliterates any possibility that might still have been there in terms of the effective functioning of coalitions. The experience of the NDA in the last ten years has been quite unique for this reason. Partners who had been with the alliance from Atal Behari Vajpayee’s time have repeatedly felt threatened in the NDA under Modi and his drive for total control. This was the point Arvind Kejriwal made after his pre-election release on bail. In fact, in his speeches, Kejriwal underlined that this was something Modi had already accomplished within his own party first, by sidelining all other leaders.

In a sense, this presents an obvious contrast with the experience of the NDA under Vajpayee (1998-2004). That was the only time the BJP managed to function in a way that carried the regional non-Congress partners together without making them feel threatened. Though the RSS-linked BJP was even then the major component in that alliance, it managed to strike a different relationship with partners for two reasons.

The first has to do with the fact that in 1996, the BJP under Vajpayee had failed to muster support from the non-Congress regional parties and ultimately could not win the floor test in parliament. That government therefore lasted only sixteen days. Most of the parties that had broken away from the Congress refused to join the BJP as alliance partners and formed a non-Congress and non-BJP United Front (UF) government.

The UF, however, was dependent on the Congress’ support, under whose pressure, within a short span of two years, the prime minister had to be changed from H D Deve Gowda to I K Gujral. The lessons of this episode were learnt on both sides. Regional non-Congress parties realised that they might be better off with the BJP and thus joined the NDA when it was formed in 1998. On the BJP’s side, still smarting from the humiliation of not having been able to muster allies just two years ago, the realisation was that it had to stick together with other parties if it wanted to be in power.

The second reason has to do with the persona of Vajpayee who, like Jyoti Basu of the CPI(M), had the reputation of being able to carry allies with him. The same Vajpayee who had failed to gather allies two years ago because of suspicions about the BJP and the RSS, had now become acceptable as political compulsions forced a change of stance.

Needless to say, the lessons of this long experience of coalitions need to be learnt by the INDIA bloc as well, and the Congress in particular.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Aditya Nigam is a Delhi-based political theorist

(This appeared in the print as 'Burden Of The Allies')