The morning of the fourth of June found India’s non-bhakt citizens curled in a fetal position. Braced against news of the four-hundred-foretold by the exit polls, sapped by a decade of electoral defeats, they had decided not to suffer the drawn-out torment of a televised count. Better to get the bad news all at once when the counting was done.

Then the WhatsApp messages beeped in. “Oye, are you watching?” “Watch, na!” “Arrey, it’s mad.” For me, it was my daughter in Brooklyn. She sent me a screenshot of a docile television channel’s early leads. The pixelated numbers on my phone’s screen were so unlikely that they seemed a cross-connection to an alternate India, a leak across the metaverse. Hooked, I turned the TV on. The rest is history.

The largest effect of Narendra Modi’s comprehensive failure to win a majority for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was psychological. Over a decade, the pan-Indian invincibility of the BJP led by Modi had congealed into a given. Over an extraordinary electoral career, Modi had always won a majority for the BJP in every election he had contested, both provincial and national. This aura of an all-India juggernaut immune to both disasters like demonetisation, and defeats in provincial elections in Bihar and Karnataka, had demoralised the BJP’s opponents in politics and civil society.

It had become hard to read the daily newspaper because the political flux that livens up the news had been stifled by the BJP’s iron grip on politics and political discourse. The 24x7 ‘news channels’ had been unwatchable for years, fronted by death-eater anchors with advanced degrees in performative sycophancy. Absurd though they were, they reigned unchallenged, as the rare island of dissent like NDTV was neutered through acquisition.

The deranging thing about the ‘normalcy’ that died on the 4th of June, was that the regime’s popularity seemed immune to material and physical suffering. A stagnant agriculture, distressed farmers, massive youth unemployment, the failure to ‘Make in India’, the carnage of Covid, the spectacular failure to even address day-darkening pollution and climate change, none of these seemed to make a blind bit of difference when it came to elections, like the assembly election in Uttar Pradesh (UP) which saw Ajay Bisht, aka Yogi Adityanath, retain his chief ministership with a massive mandate. The occasional Opposition success like the election in Karnataka was invariably overset by serial defeats, as in the assembly elections in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan in December last year.

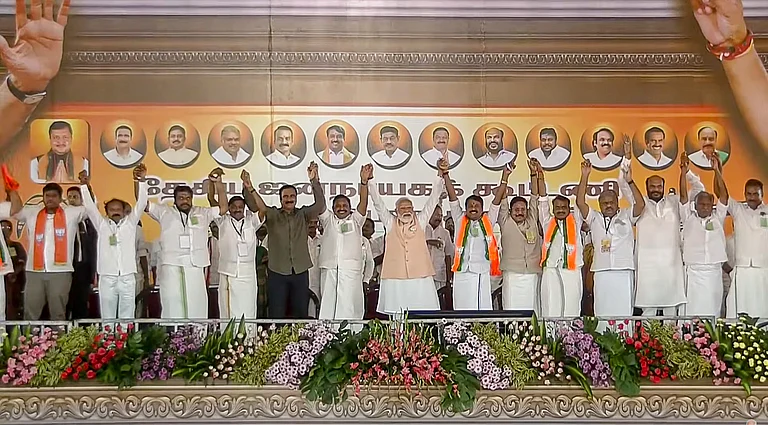

This ability to seemingly levitate, immune to the laws of political gravity, suggested that Indians at large had drunk the BJP’s Kool Aid, that fermenting brew of bigotry and aspiration, death and development. The ultimate instance of Modi’s success in remaking India in his own image was the instatement of the infant Ram in the new temple in Ayodhya. This was the apogee of Modi’s ascent, this symbolic inauguration of a Hindu Rashtra, where the prime minister of India was the jajman at the installation of Ram Lalla’s idol in a mega mandir built on the site of a razed mosque. The vandals of 1992 were celebrated as heralds of the Hindu turn, and Modi basked in his costumed persona as India’s Hindu regent.

It was this triumphalist balloon that was pricked by results that trickled in on the 4th. The BJP lost the Faizabad seat that is home to Ayodhya and its bhavya mandir, to the Samajwadi Party, which had nominated a Dalit to contest a non-reserved seat. It lost the majority of UP’s parliamentary seats to the INDIA alliance, led in UP by Akhilesh Yadav and quarterbacked by Rahul Gandhi. And in the unkindest cut of all, Modi’s majority in Varanasi, his assiduously nursed constituency, was reduced by two-thirds to a mere lakh and a half. The Modi-Yogi double act blazoned on billboards across the country, was routed in the Hindi—and for the BJP, the Hindu—heartland.

The symbolic significance of this is incalculable. The BJP had been humiliated in India’s largest state, even though it had delivered Ayodhya, beautified Banaras and literally demolished Muslim homes and livelihoods. The Hindutva agenda had been systematically implemented in this overwhelmingly Hindu state by the two high priests of Hindutva, India’s prime minister and a publicly sectarian Hindu monk; in return, the BJP had reaped local humiliation and lost its parliamentary majority.

But it was the practical political implications of the BJP’s lost majority that created a sense of deliverance. It set a precedent: the BJP could be knocked off its perch, it could be checked at a pan-Indian level by the politics of a united front. Most importantly, this united front could survive the assault mounted on it by the Union government: the frozen bank accounts, the arrested chief ministers, the weaponisation of the Enforcement Directorate and the unrelenting propaganda of the lapdog media.

More importantly, the BJP’s minority status reopened the political marketplace at the pan-Indian level which had been effectively shut down through the decade of its ironclad majority.

Now that its all-India monopoly has gone, there is room once again for the ordinary business of parliamentary politics in a subcontinental polity: the bargaining, the horse-trading, the federal give-and-take that help create political equilibrium in a country as diverse and as large as ours. The Centre’s control freakery, driven by Modi with his unending talk of ‘one nation, one election’, and his brazen bid to undermine the political autonomy of states with his touting of the ‘double-engine sarkar’, has now been thrown into reverse-gear, because his Union government now depends on the support of the BJP’s provincial allies.

Given that these allies are comrades of convenience with a long history of rancour with the BJP, this support is conditional. Chandrababu Naidu of the Telugu Desam Party has been venomously bad-mouthed by both Modi and Amit Shah in recent years. Nitish Kumar of the Janata Dal (United) is the political remake of If It’s Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium. He’s changed places so often that he asks Alexa every morning which side he is on. Neither is ideologically invested in Hindutva.

They won’t necessarily use up political capital to oppose Modi’s anti-Muslim projects like the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, and its conjoined twin, the National Register of Citizens (NRC), but at the very least, Modi will have to look outside the echo chamber of fanatical majoritarians to implement his inquisition. Also, it is unlikely that these two grizzled political survivors will lend themselves to the BJP’s ambition to rewrite the Constitution, especially since the two-thirds majority needed to initiate any amendment is now out of sight.

Observers of the political scene have begun to caution us against reading too much into the election. The BJP might have lost more than 60 seats and its majority, but it’s worth remembering that for two decades before 2014, 240 seats in Parliament would have been seen as a rock solid basis for stable governance. The other caution is that it’s a mistake to interpret the election result as a rejection of Hindutva or the resurrection of some idealised, secular idea of India.

Asim Ali, our sharpest analyst of contemporary politics, writes that the opposition should continue to focus on what he calls “…a progressive egalitarian future. The fight should be on caste and class inequality, not status-quoist secularism”. Instead of the rhetorical invocation of a secularism ungrounded in popular need, he argues that political parties opposed to the Sangh Parivar’s agenda should continue to emphasise, as they have done in this election, “…basic livelihood issues that affect all citizens”.

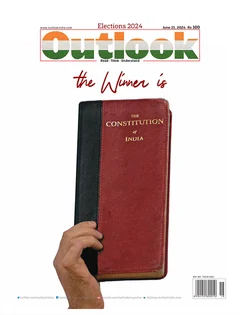

This is good advice, but it needs to be caveated. Progressives have learnt through experience that battles fought on the ground of minority rights don’t achieve the broad mobilisation essential for success or even a successful holding action. The Muslims, who led the resistance against the CAA in Jamia Millia Islamia and Shaheen Bagh, understood this as well. It is why they embedded their movement in the founding document of the republic, the Constitution. Those mobilisations were defeated for various reasons: COVID-19, principally, but also the fact that they occurred during the high noon of Modi’s Raj, against a predatory regime that used the impunity guaranteed by its super-majority to stamp out dissent with violence. The fear of this rampaging state limited the scale of solidarity that other groups outside the Muslim community might have expressed in less beleaguered times.

It makes sense not to foreground secular abstractions and minority rights to deny the BJP the opportunity to drive a wedge between Muslims and others. But while the opposition might lose its interest in explicitly calling out communalism, communalists are deeply interested in reducing politics to a slanging match about Muslims because bigots believe that this is an argument they can win. What will the response of a progressive opposition be if the BJP decides to run sequels to Ayodhya and makes the demolition of the mosques in Varanasi and Mathura the main course of its political menu through its third term?

There’s no guarantee that Naidu and Kumar will necessarily baulk at this. They have projects to complete, constituencies to nurture, clients to placate. Will a progressive opposition tactically cede this ground for the sake of the broader fight for basic livelihood? If the BJP presses ahead with its plan for a national NRC, will this canny opposition mobilise against this inquisition designed to destabilise Muslim citizenship or will it sidestep it, hoping to fight its battles on less ‘divisive’ ground? The NRC, in conjunction with the CAA, gives undocumented Indians a path to citizenship unless they are undocumented Muslims.

These hypothetical futures mightn’t come to pass. The constraints of a coalition might dissuade the BJP from pursuing a maximalist agenda, but any progressive alliance worth its name needs to have answers to these questions if only because the BJP has shown us that it is straining to ask them.

That said, it’s fine for a day or two or three, to wallow in this semblance of political normalcy, to enjoy this glimpse of an ordinary world where a rational politician might think twice before making the surreal claim that he was not ‘biologically’ born, where the exigencies of coalition government might keep the prime minister of the world’s most populous democracy from toxic slurs, minority baiting and dog-whistling. It’s a long way from here to an inclusive politics, but we should celebrate the fact that on the 4th of June, 2024, we, the people, avoided the abyss.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Mukul Kesavan is a writer and columnist

(This appeared in the print as 'The Great Escape')