Herbert Marcuse, one of the greatest German-born American political philosopher of the 20th century, in his most important book One-Dimensional Man argues that the aspiration of the poor to become rich and the aspiration of the rich to become richer, eventually blurs the line of the class divide between the rich and the poor and also between the oppressor and the oppressed. In more than one way, this analogy can be applied to the political class of India in general, and Maharashtra in particular.

Those who are not in power want to be there and those who are already there want to be there forever!

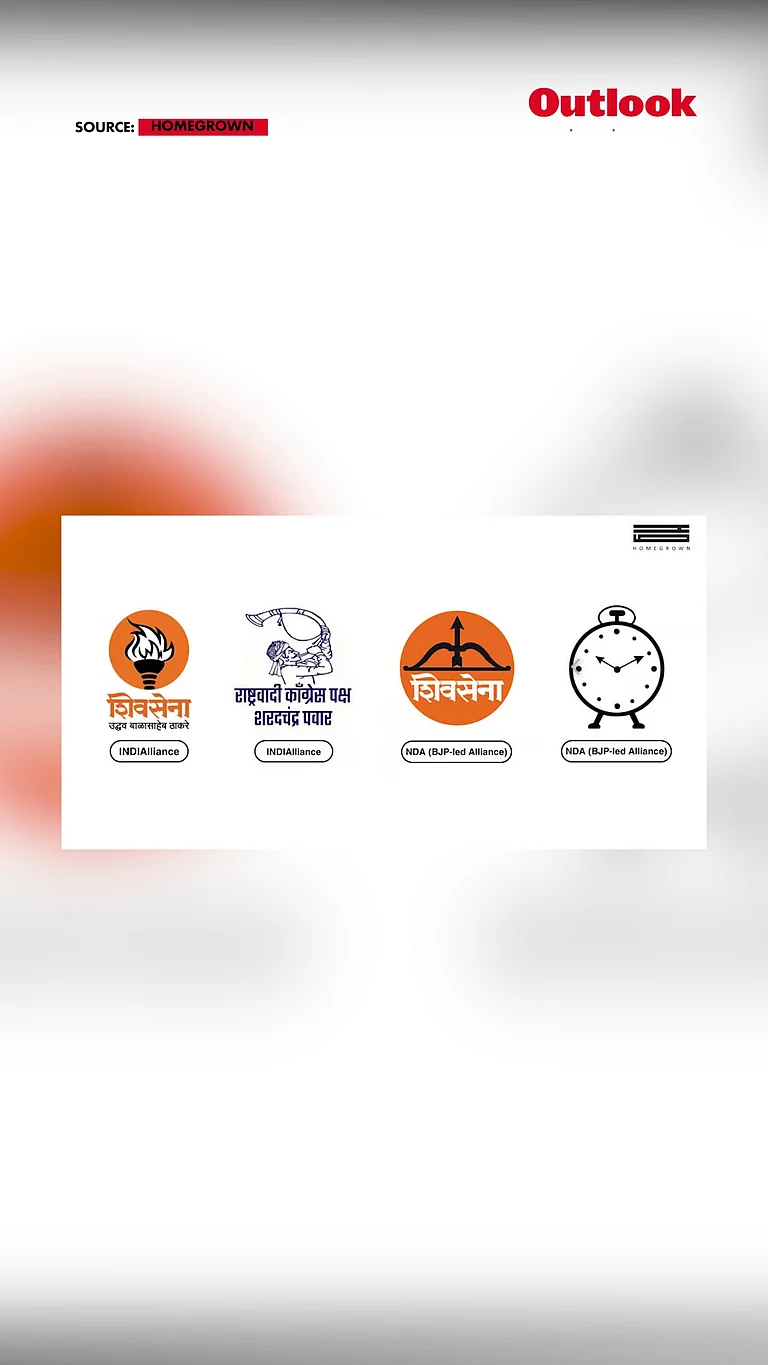

To achieve this, they are ready to give up their ideologies; rather, most of them have already given up. In the 2024 Maharashtra Assembly elections, it’s completely de-ideologised politics at play. There are six main parties in the fray in two coalitions—the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the Shiv Sena (Shinde) and the Nationalist Congress Party (Ajit Pawar) as Mahayuti, and the Indian National Congress, the Nationalist Congress Party (Sharad Pawar) and the Shiv Sena (Uddhav Thackeray) as Maha Vikas Aghadi—and there are six smaller parties allied with these two coalitions. There are a few more non-aligned parties like the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) and the Vanchit Bahujan Aghadi and others. There are also rebels or ‘vote cutters’ from all parties; there are ‘proxy candidates’ and finally, independents, whose number has skyrocketed in this election like never before.

They all have become mirror images of each other. There are no major differentiators.

Till 2019, the elections were fought between secular parties—the Congress, the NCP, the Peasants and Workers Party of India (PWP), the Samajwadi Party (SP) and various factions of the Republican Party of India (RPI) and communal parties—the erstwhile Jana Sangh that was rechristened as the BJP in 1984 and the Shiv Sena. Now, we have two factions of the Shiv Sena and two factions of the NCP, one each in both the major coalitions. So, Mahayuti has two communal parties and one secular party and Maha Vikas Aghadi has two secular parties and one communal party. This is just the beginning of the confusing de-ideologised politics at its best.

Let’s look at the prominent leaders of all the major parties. For example, Ganesh Naik, who started his political career in the Shiv Sena and later joined Sharad Pawar’s NCP, is now contesting as the BJP’s candidate. More interestingly, his son, Sandeep, who too started with the Shiv Sena, went to the NCP and then to the BJP with his father, was denied candidature by the BJP, so he has joined Sharad Pawar’s NCP and is contesting on their ticket. Take the example of Narayan Rane, former chief minister. He and his two sons started their political careers in the Shiv Sena. They all later joined the Congress, left the Congress and floated their own party and miserably failed. Now, Rane and his younger son, Nitesh, are with the BJP. Nitesh is contesting on the BJP’s ticket and his elder brother, Nilesh, is contesting for the Shiv Sena-Shinde! Chhagan Bhujbal, who started his political career as a Shiv Sainik, later defected to the Congress and then joined Sharad Pawar’s NCP, is now with the Ajit Pawar faction and his nephew, Sameer, who is considered as his shadow, is contesting as an independent.

Due to paucity of space, we are unable to share the names and details of all those who have switched sides and joined political parties they have been fighting against all their lives. But there is no end to it. Political leaders of Maharashtra are reminding us of the catchline of an advertisement—“Free flowing iodised namak”!

Corruption: No Longer a Taboo

Till 10 years ago, leaders against whom charges of corruption were levied were kept at bay. Now, corruption is no longer a taboo. All parties have fielded candidates who have either gone to jail or against whom cases of corruption and money laundering were filed and are still pending. There are also people like Nawab Malik, who were linked to none other than Dawood Ibrahim. The biggest example is that of Ajit Pawar. Prime Minister Narendra Modi had publicly accused him of swindling money to the tune of Rs 70,000 crore in a public meeting, and in less than a fortnight, Ajit joined the BJP-led coalition and was made deputy chief minister.

It’s Raining Rebels and Independents

There are a record number of 4,140 candidates in the fray. In 2019, it was 3,239—a whopping jump of 28 per cent. There are more than 150 known rebels who haven’t withdrawn from the contest. This is a reminder of the 1995 elections when more than 40 independent candidates were elected. Almost all of them had joined the Shiv-Sena-BJP government led by then Chief Minister Manohar Joshi. Interestingly, most of them were Congress rebels who chose power and money over ideology. Chances are that history might repeat itself this time too.

City-centric Ideas of Development and Freebies

In the last 30 years, Maharashtra’s politics have witnessed a major change. The idea of development and public welfare has completely changed. Earlier, farmers, issues and projects related to farmers and rural parts of the state were given prominence while shaping up the annual budget or the election manifestos. However, since 1995, after the Shiv Sena and the BJP came to power, the focus has shifted to city-centric infrastructure projects for the urban parts and freebies for the rural areas. The cooperative sector, sugar mills, cotton mills, and milk collection societies are no longer the concerns of the state government and state politics. They have taken a back seat. The same is the case with issues like farmers’ suicides, malnutrition deaths of newborns and infants in the tribal areas, implementation of the employment guarantee schemes (EGS), which are no longer at the centre stage of political debate. What these issues get is just lip service, nothing more.

There is a fear that the middle-class, the lower middle-class and the poor will no longer be involved in the political process.

And, when it comes to subjects like fiscal discipline, financial priorities, things have been turned on their heads. There is a norm about the proportion of debt to the total size of the budget, which has been thrown to the wind by successive governments in general, and the Eknath Shinde-led government in particular. More than 70 per cent of the budget is spent on revenue expenditure and slightly more than 20 per cent on servicing debt. Whatever is left—which is miserably less than 10 per cent of the budget—is available for developmental projects from the state budget. At present, all projects are debt-funded projects.

It is Only Moneybags

In a state like Maharashtra, where the average monthly income of a farmer is slightly above Rs 10,000, the declared assets of more than 95 per cent of the candidates are above Rs 10 crore! Parag Shah, the wealthiest candidate, is a builder from Mumbai who is contesting on a BJP ticket and his declared net worth is over Rs 3,300 crore. Young candidates who have hardly worked in their lives have declared assets ranging from Rs 10 crore to Rs 100 crore. They include two Thackerays, two Pawars, two Ranes and so on.

It’s All in the Family

Traditionally, there are 50-60 families of Maratha leaders who run the political show in Maharashtra and for them ideology does not matter; families do. Before 1995, they were all ‘Congressmen’. After 1995, the BJP and the Shiv Sena too have added the names of their families to the list. In this election, 26 debutants from the dynasties will be trying their luck. This will mark the entry of fourth-generation representatives into politics. For example, Yugendra Pawar and Rohit Pawar, grandnephews of Maratha strongman, Sharad Pawar, represent the third generation of the family, while Aditya and Amit Thackeray, Sujay Vikhe-Patil and Shreejaya Ashok Chavan represent the third generation, and the tallest leader of the BJP in the state, Devendra Fadnavis, represents the second generation.

A majority of the Pawars, Patils and Deshmukhs are related to each other through matrimonial ties, and this is another aspect of dynasty politics without any ideological basis.

What’s at Stake?

Since only moneyed people from some specific castes, communities and families with scant regard to ideology, political thought and social concern are occupying major political space in this election, there is a fear of complete marginalisation of issues related to the rural parts of the state. There is a fear that the middle-class, the lower middle-class and the poor will no longer be involved in the political process, except for shouting slogans and pressing voting buttons. Representation of Muslims in the legislature was already low—just nine MLAs in a house of 288 in 2014 and 10 in 2019, as against 12 per cent population in the state. In all likelihood, it will further go down and Dalits will lose their voice in state politics with a complete rout of Republican politics, earlier commanded by leaders like R. S. Gavai, Prakash Ambedkar, Ramdas Athawale and Jogendra Kawade.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Ganesh Kanate is a Mumbai-based senior journalist

(This appeared in the print as 'One Dimensional Politics')