Bangladesh’s successes have always been a development paradox. The Lancet had described it as “a mystery in global health.” The World Bank had qualified its economic successes as a “puzzle with missing pieces”. The Economist had lamented that Bangladesh’s “economic achievements are marred by grotesque politics.”

But within five decades of its creation, Bangladesh has emerged as a confident middle-income country. This was a far cry from Henry Kissinger’s denigration as a “basket case”. However, the mystery has always been about how long Bangladesh would be able to sustain its rapid socio-economic strides with an unstable democracy. With the recent student uprising, this time bomb has finally imploded.

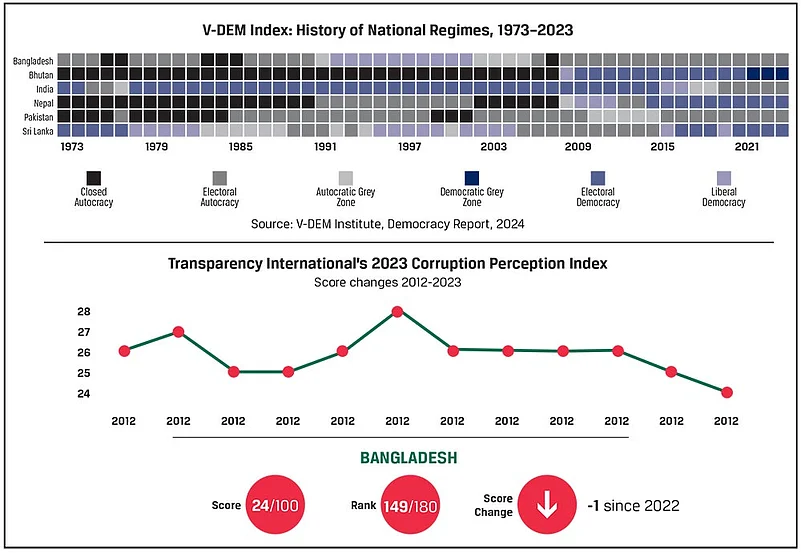

Both, the 2024 and 2014 elections had been boycotted by the Opposition. The 2018 vote, too, seemed rigged with the Awami League “winning” 302 of 350 seats in Parliament. The 2003 V-DEM Liberal Democracy Index ranked Bangladesh lower than Pakistan. The political climate was thick with intrigue, murders, forced disappearances and the imprisonment of members of the opposition party. So, the recent student revolution and toppling of the autocratic Sheikh Hasina government has not been entirely unexpected.

Bangladesh is also legendary for its gigantic street protests. Throughout the fifties and sixties, Bengali students spearheaded the Language Movement for the creation of Bangladesh. The 2018 protests by school children for road safety grew so widespread that they ensured that Dhaka came to a standstill, hit international headlines and had to be quelled with tear gas. The 2013 Shahbag protests were more overtly political as old wounds from the 1971 Liberation War resurfaced. With the 2024 ‘Second Liberation’ protests, students have finally rewritten Bangladesh’s history by ousting the authoritarian Sheikh Hasina government.

Despite this simmering political turmoil, Bangladesh has consistently achieved impressive economic growth in the last two decades. Before the pandemic, from 2011 to 2019, Bangladesh’s per capita GDP doubled. The country’s economic growth rate also averaged a healthy 6 per cent.

Since the turn of the millennium, Bangladesh has also overtaken India on a range of social indicators. Bangladeshi women, on average, can expect to live five years longer, be more literate and have lower fertility rates than their Indian sisters. Bangladeshi children are also less likely to die in infancy or be stunted due to malnourishment. They are also more likely to complete primary and secondary school.

My book Unequal: Why India Lags Behind Its Neighbours based on my doctoral research chronicles how Bangladesh (and other Indian neighbours such as Nepal and Sri Lanka) have similarly raced ahead in human development indicators.

Monopolistic Partyarchy

Apart from these impressive socio-economic strides, in Bangladesh the veneer of political democracy has also always remained ever-present. Villagers celebrate even local elections however corrupt they may be. All government primary schools conduct annual student elections using ballot papers. School noticeboards display the photographs of these elected representatives. Elections seemed to be hardwired into the Bangladeshi national consciousness. After all, they were hard-won symbols of democracy.

Till the nineties, Bangladesh had a string of coups, military dictatorships and assassinations. The nexus of politicians, military officers and bureaucrats, as the most powerful elites in the country, have had a firm grip on power. These Bangladeshi political elites have also always championed welfare policies to opportunistically safeguard their vote banks. If they do not deliver, all regimes knew that they could easily be replaced.

Economist Naomi Hossain believes that the 1974 famine cemented this unique social contract. Even in the eighties, General Ershad made primary education legally compulsory to gain popular support for his feeble military dictatorship.

After democracy returned in 1991, a new form of patronage politics emerged. For the last quarter of a century, Begum Khaleda Zia and Begum Sheikh Hasina have been elected in rotation as prime ministers. Competition between these two political rivals further fuelled a race for populist welfare policies. Sheikh Hasina’s pet healthcare project, for example, was the building of a network of Community Clinics within walking distance of every village. Political scientist Mirza Hassan has also aptly described Bangladesh as a ‘monopolistic partyarchy’ in which a ‘winner takes all’. When a particular political party is in power, it controls and politicises all civil society positions with party appointees—from “independent” commissions to professional associations.

Endemic Corruption

Corruption is also so endemic in Bangladesh that most people that I spoke to believed that to get any job, except in NGOs, one had to pay a bribe. A health worker who had been honestly appointed 35 years ago said that the times had changed considerably now. A health volunteer for immunisation chimed in, “no bribes, no jobs.” I heard this refrain everywhere. Parents told me they prefer to spend on their daughter’s dowry rather than pay bribes to get them jobs. This systemic corruption also induces health workers, teachers and other employees to use illegal means to make money after they secure jobs. They indulge in private tuitions, black marketing of medicines and other means to pay off their bribes.

Transparency International’s 2023 Corruption Perception Index ranked Bangladesh 149 of 180 countries. This was the worst score in South Asia apart from Afghanistan. Seventy-two per cent of Bangladeshis especially reported grave corruption in government services.

Jobless Growth

Like Satyajit Ray’s film Mahanagar, the biggest worry for young Bangladeshis seemed to be “chakri” (jobs). In the last decade, Bangladesh has been particularly plagued by jobless growth. There has been a decline in employment elasticity, especially for men.

So, the reinstatement of a thirty per cent reservation quota for families of “freedom fighters” expectedly touched a raw nerve among students. The youth unemployment rate in Bangladesh of 15 per cent is three times higher than that for all adults. Gen Z has been systematically finding their aspirations throttled. Since the pandemic, the International Labour Organisation projected that the number of unemployed Bangladeshi youth increased from 0.4 million to 3.5 million. The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics also estimated that students with a tertiary education suffered from the highest levels of unemployment. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) assessed that in 2023 around 47 per cent of graduate students in Bangladesh were unemployed.

Bangladesh’s economic and social progress has undoubtedly increased the confidence of its citizens. But with their employment prospects stifled, the anger of university students was bristling.

Their idealism and public spiritedness should also not be underestimated. One sleepy summer afternoon in 2016, outside Dhaka University, I saw a strange sight. Around a hundred children were seated on a large blue tarpaulin sheet laid on an empty backstreet, reading from their textbooks. On making enquiries, a hijab-clad university student told me that every Sunday she and her classmates volunteer to teach slum children nearby. Even after the recent protests, with police personnel on strike, Bangladesh university students have taken over managing the traffic nationwide and protecting places of worship.

In a country with such intense commitment and resilience of citizens, democratic aspirations cannot be curtailed forever. Sooner or later, political freedoms, too, would have to be expanded. After all, the revered Bengali poet Kazi Nazrul Islam’s most famous poem is Bidrohi (Rebel).

The tinderbox was waiting to explode. The writing was on the wall.

The South Asian champions in human development, Sri Lankans, too, recently revolted to unseat the corrupt Rajapaksa dynasts.

Swati Narayan is an academic, activist and author. She teaches courses on social policies and universal healthcare.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Myth Of A Miracle')

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)