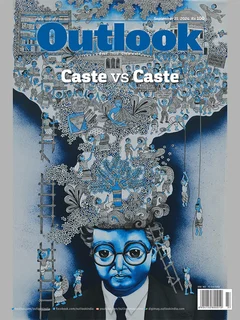

The Supreme Court’s seven-judge constitution bench ruling on sub-classification of Scheduled Tribe (ST) and Scheduled Caste (SC) categories required an exhaustive study and a report by a commission. In fact, many from the SC and ST communities felt the ruling itself should have been preceded by a database for the ready reference of the SC.

The message of the SC judgment is two-fold. First, the country should go beyond the parametres of the Constitution to ensure justice to the genuinely deprived. However, the creation of the concept of creamy layer or sub-categorisation of SCs and STs is not allowed by the Constitution. And second, the SC needs to know which sections are truly deprived.

“Such a ruling of the constitution bench of the SC should have been accompanied by a proper database on the economic and social situation of the SC-ST communities. And for this, the government should have constituted a commission to study their situation and come up with an exhaustive report first,” opined Prabhakar Tirkey, the director of Jharkhand-based Centre for Tribal Studies. Jharkhand is known for its independent tribal opinions on socio-political and economic issues and has a long history of tribals fighting for their rights to political self-determination.

During the tenure of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, the Ministry of Tribal Affairs had prepared a draft for National Tribal Policy, which never progressed beyond. Tribal groups from across the country have been urging the present government to prepare and promulgate such a policy but no thought has been given to this serious demand yet at the government level.

Article 339 of the Constitution makes a provision for setting up of a commission to study the socio-economic situation of the deprived communities, and it also says that such commissions should be set up every 10 years by the President. After the Dhebar Commission of 1961, no such commission has been put in place to study the situation of tribals in India.

After the Dhebar Commission of 1961, no commission has been put in place to study the socio-economic situation of tribals in India.

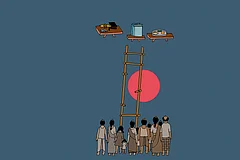

There is another argument that has been made by the educated class in the ST category against sub-categorisation. First, the reserved posts, particularly in the senior ranks, have not been filled up by the recruiting bodies by putting across the argument that meritorious candidates were ‘not found’. “This leaves the scope of filling up of the senior ranks by non-tribal candidates. When such is the actual reality, the creamy layer concept will keep children from privileged families outside the reservation facility, and children of unprivileged families will never be able come anywhere near qualifying for the posts,” says Ashish Lakra, a retired Government Medical Officer in Jharkhand. He feels institutions like medical and government engineering colleges—like the IITs and NITs—will permanently keep tribal candidates out if the concept of creamy layer is applied to the ST category.

Among the tribes, the other side of the story is also true. After Independence, many groups and families hugely benefited from the reservation facility provided to them. This indeed has created an ‘elite group’ in our society in recent years. Children of these groups do monopolise government jobs and seats in institutes of higher education.

The SC bench probably had this in mind when it gave its ruling. However, sub-categorisation of SCs and keeping the creamy layer, if at all, completely out of the reservation facility, would be too general a thing to do. Though most beneficiaries among SC and ST communities decline to accept the SC ruling, reserving lower-rank jobs, particularly Class IV jobs for such families, which never managed to take benefits of the reservation, could work towards delivery of better justice to the actual deprived in the tribes.

The SC community in India is a bigger group as compared to the STs, though the two groups are completely different from one another. While the SCs face discrimination and atrocity in the name of varna system, the ST community—which is a ‘tribe’ and not a ‘caste’, and thereby does not come under varna system—has its peculiar problems that are beyond the normal comprehension of the caste society. However, economically, the SCs may be better off compared to the STs for the simple reason that STs have a lower ‘satisfaction level’, and do not so much believe in creating ‘surplus’.

“Our Constitution does not allow sub-categorisation of the SC and ST groups. Therefore, the SC ruling is beyond the Constitution,” said H L Dusad, a noted Dalit writer based in Lucknow. He said, the SC, ST and OBC population in India collectively own only 12 per cent of the wealth and the rest of the wealth is owned by the savarnas. “When the court gives such a ruling, it is not well-informed about the real situation of the SC-ST communities. The court’s intention does not appear to be right,” Dusad added. He even went on to add that the concept of ‘creamy layer’ does not figure when many posts reserved for SC candidates have been kept vacant, saying that suitable candidates have not been found.

Many in the mainstream society think that reservation facility for the socially and economically weaker section is injustice to them and is against right to equality. This argument is based on the question of ‘right to equality’ of the Constitution, whereas the reservation facility has to be seen in the context of ‘right to justice’. ‘Marks’ alone is not the criterion of ‘merit’, for the word merit itself is a judgment from a non-neutral standpoint.

Tribal students, whose mother tongue is never Hindi or English, are made to study in a language that is the language of the mainstream. They are judged on that criterion. They are also made to study non-tribal subjects that are mostly alien to them. On the other hand, students from the mainstream do not have to study tribal concepts or the language. Thus, even education itself is not a neutral ground for tribal students. ‘Merit’, thus, is an incomplete definition if it is reduced only to ‘marks’ in a competitive examination.

Moreover, the ‘Dronacharayas’, who are supposed to be neutral, are not and would not like to allow Eklavya to take on Arjuna.

In fact, when an individual joins a job or a company from a different background, that itself is a merit for his presence adds to the ‘common wisdom’ of society and makes the society richer. This may be particularly true for a ST candidate who comes from a different background altogether. Books like Wisdom of the Crowd by noted thinker James Surowiecki, which relates to diverse collections of independently deciding individuals, rather than crowd psychology, shows how individuals of different backgrounds actually make an institution richer.

After all, the deprived, especially those from tribal communities, do not have a say in any decision-making process or in the running the country. The court can turn its wisdom towards this as well.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Santosh Kiro is a Ranchi-based academic who has authored books on tribal philosophy, history and politics

(This appeared in the print as 'Crème de la Crème')