Museums in India are also known as Ajaib Ghar—the house of the strange. The same term exists in many Indian languages. In Marathi, it is called Ajab Bangla. The collection of objects and antiquities started getting showcased under one roof, and that’s how museums in India were born.

The princely states, being the seat of power in their respective regions, also had their treasure houses that were open to public viewing. The colonial administration started showcasing collections of antiquities, materials unearthed from archaeological excavations, stuffed animals, birds, and lives of various communities in the form of small sculptural models. Interestingly, the French occupation in Karnataka coast produced a picture album of various castes and communities as part of a picture manual for the French administrator in their territories. Thus, it became a picture resource for the people of India.

The likes of Herbert Hope Risley studied different tribes in India and produced a photographic documentation. As far as community or peoples’ museum is concerned, there are many museums showcasing the lives and culture of Adivasi communities which the urban population often deems as backward and undeveloped. In post-Independent India, many museums emerged as part of government initiatives, and nowadays, private museums have also come up. Military history in museums in India carries the narratives of the dominant communities whose names still exist on the regiments.

There is a general perception that only the past is museumised and not the present practices. These strange ideas and attitudes take away focus from many problematic social issues in our society. It is ironic that even after India became a republic, the Indian public at large gets politicised only in terms of casting votes. This hardly helps our society emerge as a just society representing modern democracy.

How About a Museum of Untouchability?

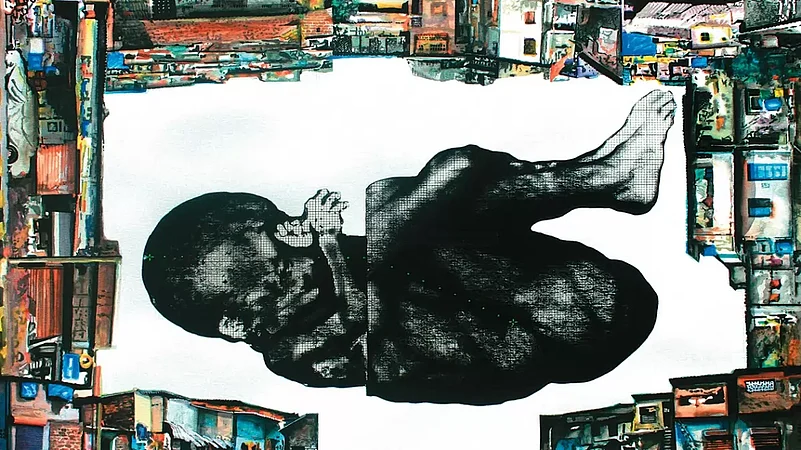

Resolving conflicts to create a better society by constitutional means is the desired dream but the practice of untouchability and the heinous crimes that are committed in the form of brute killings, rapes, and public beatings are still in practice. In this context, what are the possibilities of conceptualising a Museum of Untouchability? Any atrocity of savarnatva is a psychotic perversion and its manifestation is always brute, in conflict with humanity and moral human values. Who all are afraid of a Museum of Untouchability? Why is there a resistance to such an idea?

The Constitution of India has banned untouchability. It does not recognise a caste but a group of castes for affirmative action. Any museum begins with history, so the Museum of Untouchability has to also begin with history. However, untouchability being the disease of the mind, its material manifestation is a difficult process. Nevertheless, the museum will have several sections showcasing the ideas and objects of atrocities.

The museum can be divided into several sections. After crossing the first entry gate, the viewers shall be asked to remove their chappals/shoes and they will be made to walk to the next entry gate holding their footwear in their hands. This walk-through in broad daylight will make them realise how one feels when he/she is not allowed to wear footwear while crossing a caste-Hindu locality. They will be allowed to wear their footwear after a display flashes “you have crossed the territory of caste-Hindus. Now you are entering a more liberal place, so wear your footwear.”

The historical section would showcase verses referring to ‘untouchability’, mainly the Dharmashastras and the Narada Smriti. The travel record of Fa Xian—a Chinese Buddhist monk and translator who traveled by foot from China to India to acquire Buddhist texts in the Fifth Century CE— has written about localities of Chandalas outside Mathura.

Verses written in shilp text have talked about designated places in temple complexes where shudras had to stand at the mukhamandapa (entrance gate) and untouchables had to stand outside. A model can show the difference in treatment meted out by colonial white men who had no untouchability syndrome and the Indian caste-Hindu Brahmin consumed by untouchability syndrome.

Such sculptural models can recreate realities of society in museum spaces. These models can show untouchables with brooms tied to their back and sputum pots hanging in their necks. The section could include Savi Sawarkar’s paintings on untouchability depicting how untouchables were subjected to the above-mentioned humiliation. It can include installations made by various artists on untouchability.

The next section could be an experience of filth and dirt. It could be created with artificial dirt and have installations of photographs by Sudharak Olwe and Palani Kumar on manual scavengers. The room can be made to smell like dirt and excreta and viewers will have to pass through the narrow room to experience the stench. Such unique-particular is an important signifier for the public to understand the state of untouchables in the “shining” and “skilled” India that is also a trillion-dollar economy.

The next gallery shall showcase the experience of humiliation. Visitors will be made to ride an electronically devised horse wearing a turban and putting on a fake mustache (which will be optional). The horse will be stopped after covering a distance. Images of a group of men will appear instantly from the side walls and start abusing the person for riding a horse wearing a turban. The viewer will be given headphones and will have to choose the language option of his choice, which will have Indian and foreign languages. Recreating such a scene will enable caste-Hindu viewers to understand how inhuman his/her community behaves toward untouchables in rural as well as urban India. Such an experience is necessary to understand how inhumane our society has become over a period of time.

A section of the museum will also recreate “filthy” areas of house dwellings. It will have sound and smell effects based on the living conditions of the communities as described in the life narrative of Upara by Lakshaman Mane. A viewer will be made to sit at these dwellings and walk through the dingy lanes created in the room with sound, light and smell effects.

The next section shall be a compact room with a passage and it will smell of human excreta. This will make viewers experience the plight of manual scavengers and sewer deaths. They will then have to pass through a huge pipe showcasing the drainage and enter a hall where realistic paintings and models which will showcase the tormenting of the bodies of untouchables by the caste-Hindu communities.

The life-size models will display the plight of untouchables in two landscapes—urban and ruler. The urban set up will exhibit the killing of a Dalit boy by the family of the caste-Hindu, whereas the rural one will exhibit mob violence in public glare. These sculptural models will be live, and the violence will be enacted by other models. The hall will be named as the ‘chamber of violence’ and the models will be created based on the many events of atrocities as per the reports of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Commissions of the Government of India.

A subsection in the hall will showcase photographic images of violence that have been recorded in the recent past across the country. Another subsection will have digital projections of the images of beatings of the Dalit youths—male and female—in full public glare, including the Una incident and other such instances. Another subsection will showcase the defamation of Ambedkar statues. An audio will narrate instances wherein a caste-Hindu person kills a youth for having an Ambedkar song as its caller tune.

The next section of the museum will have leather works, mainly models involved in the skinning and tanning process, and showcasing of objects made of leather, such as foot wares and bags. Tools and small models of tanning process can be put on display to showcase not just the process but also the labour that goes into it and the amount of knowledge required. The section will have the history of how the leather industry has evolved as an exclusive profession over the decades.

The same section will depict the digital demography of cities and villages and how they have been detrimental in creating ghettoisation. Colonial maps can be used. The past and the present can be shown on the same digital surface. Digital projections could be made on a large screen to show viewers how demographic division is followed diligently. The sectional space can have Madhubani paintings, mainly Khobar, created by untouchables. It will also have objects made for household consumption. Many of these objects are made by the untouchable communities.

The last section of the museum will depict the struggles of the community and the work of people who fought for it. Important incidents like the event of the breast tax in Kerala, the Bhima-Koregaon battle, Mahar and Chamar regiments, the opening of a well for untouchables by Mahatma Phule, Mahad Satyagraha, temple entry agitations, the historic Round Table Conference, and the struggles of manual scavenging by Bezvada Wilson. A single showcase will display passports of untouchable communities and embarking stamps. They migrated to foreign land and were the first Indian migrants during colonial times.

It will also have on display works of personas who mattered the most, including saints like Buddha, Kabir and Ravidas, as well as Mahatma Phule, Ayothee Thass, Narayan Guru, Dr BR Ambedkar, etc. At the end of the museum tour, the visitors will have to take resolve that they would not believe in the concept of untouchability or practice it and will follow the Constitution of India in letter and spirit.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This article appeared in the print as 'Museum of Untouchability')

Y. S. Alone is Professor, School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi