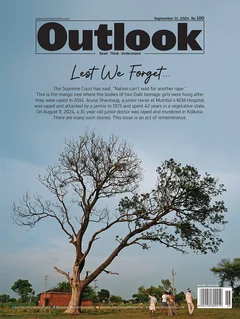

This is the cover story for Outlook's 11 September 2024 magazine issue 'Lest We Forget'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

Savitri Devi’s (name changed) home is a windowless four-walled structure roofed with corrugated metal. The only comforts are a dim camping light and a rickety pedestal fan. Since May 27, 2014, when her husband Ramesh Lal (name changed) discovered the corpses of her 14-year-old daughter and 11-year-old niece, hanged from a mango tree in a field just 600 metres from their home, this dark room has been the only place the 55-year-old woman feels “somewhat safe.”

Sitting on a sagging charpai that faces two plastic lawn chairs—the only furniture the Lals own—Savitri Devi says, “I only leave my house if I have some work, and then I come right back. Before it gets dark, I always come back and stay inside, no matter what—all the women in our family, and the girl we have left, do this.”

It’s been ten years since the Lal brothers found their children’s bodies. Every day, they go to labour in a Yadav landlord’s field a 100 metres away from the mango tree on which their daughters’ bodies swung, tiny shoes fallen onto the dirt. “The bottom of their feet was full of thornes,” says Sona Lal, tears welling up in his eyes.

The only little girl left in the Savitri Devi’s family is her youngest niece; Umesh Lal’s (name changed) five-year-daughter, younger sister to a girl whom she will never know about if her father can help it, he says. “Right now, she’s young, she is not afraid. But I am.” Sighing, eyes wide with an unceasing grief, he explains, “The men who killed my daughter are free, unpunished, and live on the other side of this village.”

Pappu Yadav, Urmesh Yadav and others got bail in 2015. Only Pappu was summoned as an accused in October 2015. For allegations of sexually assaulting and killing two minor girls, Urmesh and others spent six months in jail. The Lals challenged this order in the Allahabad High Court, pleading for the bench to summon Urmesh and the others as accused in the case. The application, filed in 2016, has been pending before the court for eight years.

“Your girls will be returned in two hours, a policeman told me”

According to the 14-year-old’s parents, Savitri Devi and Ramesh Lal, they noticed that their child and their niece were missing around 9 pm. Savitri Devi called Ramesh at work, and upon hearing this disturbing news, the father was quick to come home and organise a search party by 10 pm. When at 11pm, they still hadn’t found the girls, Ramesh went to the local police chowki.

“Police made me sit there—wouldn’t listen to me. Then they asked if we had looked for them or had just showed up straight here? I told them, ‘please look for them, don’t say wrong things. This is a matter of our izzat, so please look for her.’” Finally, an hour later, a police officer (who has since transferred out) agreed to look for the Lals’ girls.

By that time, Nazru, a resident of the village, had told the police that he had seen a group of boys, led by Pappu Yadav, dragging the girls away. “It was dark, but I recognised the girls because I live near them and I know the family. I tried to fight with Pappu to save them but the boys pulled out a katta (handmade gun) and at point blank range they told me to leave them alone ‘or else.’” It’s been ten years since that fateful day but Nazru’s voice continues to hold his guilt. “I should have fought harder,” he adds.

Upon receiving this information from Nazru, the police, and the Lal brothers began searching for Pappu Yadav. They found him hiding in someone else’s house. For Ramesh, the scene is as fresh as it was on the day. “We were standing at the entrance and Pappu and some boys were sitting on a charpai inside. From the gate, I begged him to please return my girls. Darogaji (police officer) arrested him there.”

Once in police custody, Pappu confessed that he had been with the girls before coming to the place where the police found him. “He said, ‘Yes, I had the girls,’” recalls Ramesh Lal.

At that moment, the family still had hope they would find their daughters alive. But then, SI Chattrapal Yadav walked into the police station.

“Everything changed,” says Ramesh. He tried to leave the chowki to go to the main police station, but Chattrapal “got a lathi” and threatened the brothers. “He was ready to hit me and he wouldn’t let me leave to look for my girls, saying, ‘I’ll put handcuffs on you and lock you up,’” says Umesh. When the brothers pleaded with Chattrapal to let them go look for their girls, or to go to Pappu’s house and check for them, suddenly the chowki’s policemen turned violent. “Darogaji also kicked me. I started grovelling ‘Please let my girls go.’ The police officer Chattrapal said, ‘your girls will come after two hours,’” recalls Umesh. The brothers were beaten with a belt and kicked out of the chowki.

At four am, the next morning as dawn was breaking, Chattrapal told them to go to the field where they work. Their girls were hanging from separate branches on a mango tree just a few feet away from the field where they still work.

“We don’t want their charity; we want justice”

A photo from the village showed the bodies of the two girls, dressed in green and pink tunics and pants, hanging from the mango tree. Their heads hanging lifelessly, their eyes closed forever. This photo, which caused a global furore, is the only memento of her daughter that Savitri Devi has.

“I used to look at the photos we have and get very angry. Eventually, a few years ago, I burned all her photos. It is part of her legal file. Every time I used to look upon them, I used to feel sad, angry, but mostly I would miss her,” she says.

In June 2014, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) condemned the alleged gangrape and murder and started a Facebook petition demanding justice for the victims and “immediate action against the perpetrators.”

Police arrested Pappu, Urmesh, and SI Chattrapal Yadav. However, Chattrapal got only a suspension for his alleged role in the case, and was transferred out of Budaun within six months of the incident.

When courts gave the case to the CBI, the Lals say they were “hopeful.” However, the premier investigating agency’s insensitive behaviour towards them, and their deceased daughters shocked them.

“I was distraught when the CBI came to us, and they would ask horrible questions about my daughter—what she wore, how she behaved with boys, what sort of a girl she was. One of them, I remember his name was Arvind, said to us: boys do these sorts of things, they are boys,” says Savitri Devi.

Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) chief Mayawati and Home Minister Rajnath Singh visited the Lals’ home, but no one came from the camp of Akhilesh Yadav’s, the then Chief Minister of UP. The family alleges that Shiv Sharan Kushwaha, Jan Adhikar Party chief Babu Singh Khushwaha’s brother visited them. “He came and gave us a briefcase of money telling us to stay quiet. We returned it right there; we don’t want charity or money, we want justice,” says Savitri Devi.

Outlook’s reached out to Khushwaha for a comment but received no reply.

Nine years, a case stands still

“The only progress in this case was made when the media was here,” says Syed Naqvi, a Budaun-based lawyer who represents the Lals before the district’s POCSO court. It was in front of Naqvi that the CBI filed its closure report, giving a clean chit to all accused despite two eye-witness reports and an extra-judicial confession. The POCSO court rejected the report in October 2015, but only summoned one accused: Pappu Yadav. On Naqvi’s advice, the Lals filed an appeal before the Allahabad High Court in 2016 pleading for summoning of the remaining accused in the trial. The application has been pending before the court since.

The family, which makes Rs 300 on a good day, pays their lawyer Rs 6000 per court appearance. They say the CBI counsel, the State’s prosecutor in this case, has never spoken a word to them. Before Outlook mentioned it, both the couples, educated only till the fifth grade, were unaware that the State’s prosecution was a lawyer on their behalf. They were also unaware that they had the option to appeal before the Supreme Court in the case of such a long delay.

Ramesh pointed out that being unaware was not their only hurdle. “What should I do—can I go to the SC when I have no money?” he asks.

Meanwhile, the accused have moved on with their lives. Urmesh is now married with a one-year-old daughter.

While the world has moved on from the Budaun case, the Lals live in a limbo-state. The women hardly leave the house. “If I go out, I may see them (the accused) and I can’t stand that so I don’t go out,” explains Savitri Devi. She adds that she doesn’t “feel safe outside after it gets dark.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Her daughter’s death, and the subsequent nine-year-long trial, has taken a toll on Savitri Devi’s physical and mental health. “There are times when my heart just starts pounding, and I can’t breathe. In those moments, I am filled with a rage like I’ve never felt before, and I don’t know why it happens,” she says.

(This appeared in the print as 'They Didn’t Cut The Tree')