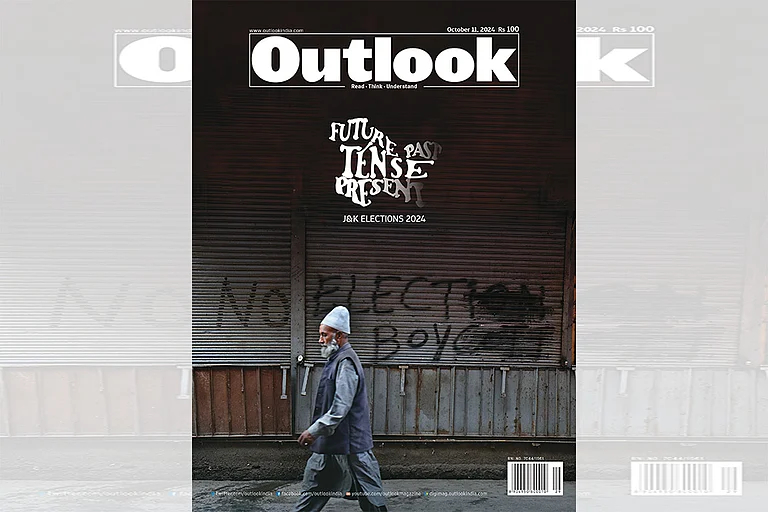

This story was published as part of Outlook Magazine's 'Future Tense' issue, dated October 11, 2024. To read more stories from the Issue, click here.

It has been about five years since the abrogation of Article 370 and yet a profound ambivalence still lingers in the air in Kashmir. The people remain caught in a web of uncertainty—torn between two competing realities. On the one hand, there is an undeniable sense of loss—the stripping away of a special status that once defined the region’s unique identity within the Indian Union—and on the other, there is a tentative hope that perhaps this new order will bring opportunities that the past had failed to deliver. But the question still haunts the Valley: Was the removal of Article 370 a blow to their autonomy or a gateway to a more prosperous future? The answer, it seems, is elusive. Each person harbours their own truth, their own sense of what has been lost and what may yet be gained. And in this symphony of emotions, where grief and hope play out in uneasy harmony, one thing is clear: no one quite knows which note to strike.

Whatever happened to Article 370 and whatever emotional toll it has had on the minds and souls of the people of Kashmir, time has kept its steady pace and life has never ceased to exist in this part of the world, as was otherwise assumed from time to time. Time, in its implacable stride, continues its course. Yet time’s steady march is not without irony for it moves like a river, cutting through mountains yet softening the stone. As we see in Kashmir, there is a curious and perhaps unsettling normalcy that has taken root. The streets are no longer echoing with the chants of protest, the strikes that once paralysed the Valley have become relics of a past era. There are no more stones hurled in anger, no more children rendered blind by the cold brutality of pellet guns. Kashmir, once a land of unspoken grief, has found itself lifted from the prime-time news cycle where once it was a constant subject of debate. A silence thick as a mist has enveloped the Valley, but it is a silence that holds its own secrets.

This silence, however, is not the void it appears to be. Beneath it, a new fire has taken hold. But whether this fire burns with the quiet determination of democracy or smoulders with unresolved tensions is yet to be known. After a decade-long interlude, the people of Kashmir are returning to the polls. The legislative election, long delayed, now arrives like a long-awaited monsoon, but with it comes a sense of ambiguity. Does this new season of political life promise a novel dawn or does it mask a deeper unrest? What does this return to the ballot truly signify? Is it simply a pragmatic act of choosing a representative or is there something deeper, something unspoken, bubbling from the depths of Kashmir’s soul—an emotion too elusive to be named?

A transition is unfolding. The people, especially the youth, are no longer content with the politics of grievance. Thirty years of conflict have shaped a generation that now hungers for solutions.

The sight of people queuing outside polling stations—people who once swore to boycott the very idea of Indian democracy—feels almost surreal, as if a new chapter has begun without anyone fully understanding its implications. This time, the act of voting is not merely a civic duty, but a symbol, perhaps even a rebellion disguised as participation. But is this participation a step towards empowerment or a surrender to a new subtler form of control? The recent parliamentary election saw an unprecedented surge in voter turnout in Kashmir. The victory of Engineer Rashid, then jailed, now out on bail, speaks volumes. Contesting from the much anticipated North Kashmir seat against political stalwarts like Sajjad Gani Lone and Omar Abdullah, Rashid’s triumph was more than just an electoral win. “Tihar ka badla vote se” (vote to avenge imprisonment) as his supporters chanted, a slogan that condensed into five words the complexity of emotions swirling through the Valley. But even this victory leaves one to wonder: does it mark a genuine shift or merely a fleeting moment of symbolic resistance? And what of this metaphor, this poetic inversion of history? It tells us that the people of Kashmir, after decades of being treated as pawns in a greater game, are beginning to find agency in the very system they once rejected. The people are voting, but what are they voting for? Are they casting ballots in protest, choosing those who speak the language of separatism or are they seeking something more tangible?

There is no simple answer, but one thing is clear: a transition is unfolding. The people, especially the youth, are no longer content with the politics of grievance. Thirty years of conflict have shaped a generation that now hungers for solutions, not for slogans. Perhaps by casting their votes, the people of Kashmir are not merely choosing candidates; they are choosing to live.

Yet this choice is fraught with contradictions. The initial desire to participate in elections may well be less an embrace of democracy and more a calculated protest—a way of sending a message to Delhi as we see potential candidates filing nominations from jails and many who have separatist backgrounds. In casting their votes, many may feel they are striking back, resisting the forces that have tried to reshape their identity. But to dwell on this irony is to overlook a deeper unfolding process. The more profound truth is that knowingly or unknowingly, the people are turning to the ballot not just as a form of protest, but also as a means to seek answers to their everyday problems. And as they do, the act of voting, even if born out of dissent, becomes a step towards something larger—towards a system that can absorb and transform these emotions.

Who is elected matters less than the act of the election itself, for this signals a subtle but significant shift in the sensibilities of Kashmiris—a shift towards accountability, towards demanding better governance and towards bridging the deep chasm that has long existed between the bureaucracy and the public. Over time, democracy has a way of softening even the sharpest edges of dissent. What begins as a protest vote may, in the long run, morph into a demand for solutions, for concrete improvements in daily life and for governance that responds to people’s needs. And this is where the transformative power of democracy lies: in its ability to take in protest, dissent and disillusionment, and slowly turn them into participation, dialogue, and ultimately resolution.

This quiet revolution, this subtle shift, in the way Kashmir engages with democracy, may well be the most profound transformation of all. For in voting to choose their leaders—whether out of frustration, hope or resistance—the people are not merely responding to the present, they are shaping their future. And in doing so, they are reclaiming their right to dream. In a land where dreams have so often been deferred, this act of choosing—no matter its motivation—plants the seeds of a new possibility. Democracy with its resilience and its capacity to evolve will, in time, absorb these conflicting emotions, transforming protest into progress and disillusionment into a new tentative belief in the future. This, above all else, is the most radical act of all.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Mohammad Tabish is based in Kashmir and is a Chevening Scholar

(This appeared in the print as 'A Requiem for a Dream')