As young officers in the Indian army in the late seventies, we learnt that the Line of Control (LoC) is a zone of NWNP (No war no peace). Over the years we saw the scenario change into ‘forever at war’, as India got embroiled in fighting a hybrid war waged by Pakistan, using jehadis as proxy. The hostility manifested as terrorist actions, gun duels along the Line of Control, Border Action Teams (BAT), propaganda, indoctrination, radicalisation of the population and so on. Several new coinages came into the lexicon to describe the state of affairs—fragile peace, situation simmering, pot boiling and so on; semantics for justifying and tolerating abnormality as the ‘new normal’.

For too long, India has fought this proxy war with two self-imposed limitations. First, geographical i.e. the Line of Control is the ‘Lakshmanrekha’. Second, the type of force i.e. fight primarily with the army, CAPF (Central Armed Police Forces) and state police. Employ weapons only up to a certain calibre. India, unlike several other countries, has not used air power and artillery for counter-terrorist operations. So inviolable was the ‘Lakshmanrekha’ that even in a situation like the Kargil war we chose to uphold the sanctity of the ‘Line of Control’.

In a significant departure from this position of restraint, post the September 2016 attack on the army base in Uri, India decided to shed the first limitation. It took the war across the Line of Control to strike at some forward launch pads used for infiltrating terrorists by their handlers in Pakistan. In responding to the Pulwama attack, India chose to shed the second limitation on the type of force. India retaliated on February 26 with surgical air strikes at the sprawling Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) training camp in Balakot.

Freed from hitherto prevalent political shackles on force, time and space, the planners were able to go for a choice of target, timing and packaging of force that was simply brilliant. The Pulwama attack was claimed by the terrorist outfit JeM, therefore the target of retaliation was its main training camp at Balakot. The air force package employed was comprehensive; including components for early warning, ground attack with high-tech target designators, protection against potential counter air operations by Pakistan, and post-strike damage assessment. Pakistan was given enough opportunity to react against the perpetrators of Pulwama. Despite the eleven-day delay in the process, both the employment and deployment of the force ensured adequate operational surprise.

India’s foreign secretary described the operation as “intel-driven, non-military operations to pre-empt terrorist attacks”. Having shed both the geographical and force limitation, India’s retaliation to the Pulwama attack focused specifically on significant terrorist targets. Yet control was exercised as the retaliation steered clear of military or civilian targets.

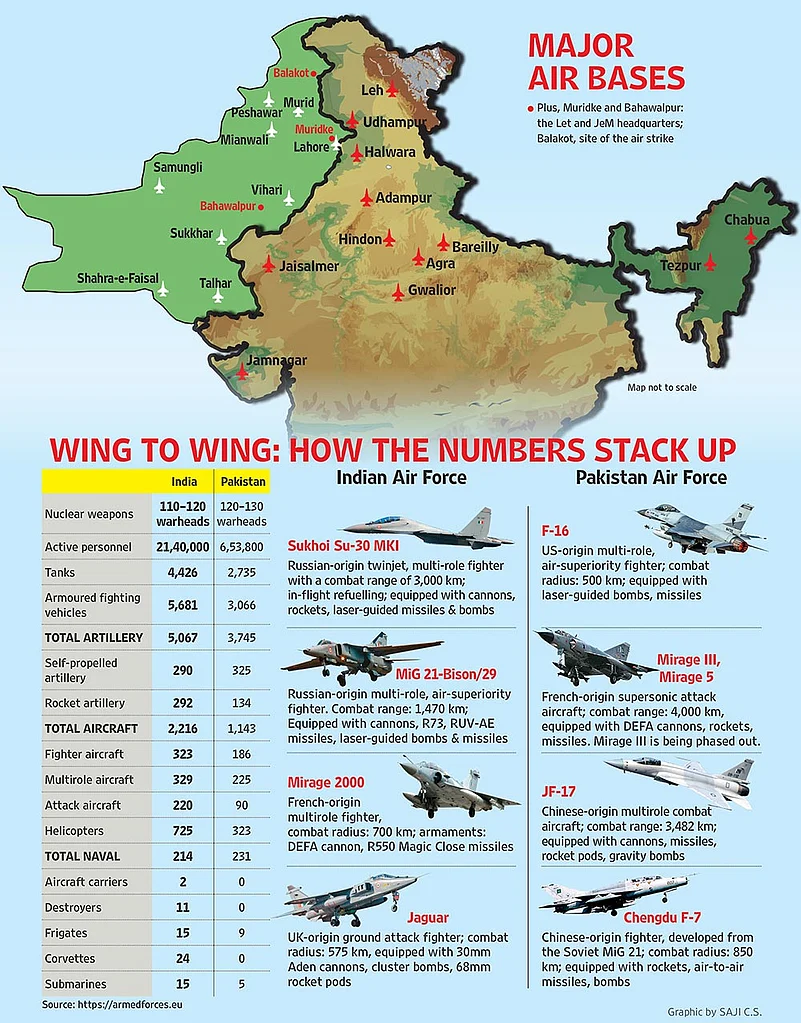

The Pakistan air force retaliated to India’s strike a day later—February 27—with fighter aircraft bombing targets along the Line of Control. Describing the PAF action, Pakistan’s official spokesperson said, “Pakistan’s fighter aircraft locked on to military targets, but fired away from them.” Ridiculous as that piece of communication sounded, the spokesperson tried to clarify their intention as “to demonstrate capability and resolve to retaliate without causing collateral damage”. There’s obviously a charade of restraint, and an attempt to appear to be the victim of the conflict. In the ensuing fight, a Pakistani fighter was shot down by India, while India lost a fighter aircraft whose pilot ejected and was taken into custody by Pakistan. The Line of Control is since active with shelling by both sides.

Pakistan upped the ante in the morning by engaging military targets, and by the evening Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan was attempting to control the situation by offering to engage in dialogue to resolve all disputes. Imran Khan may have belatedly expressed some pro forma regret for what happened in Pulwama, but has not shown any desire to act against terrorists and their handlers operating in Pakistan. By choosing to strike at military targets in India, in response to India’s strike against terrorist targets, Pakistan has provided live demonstration of its strategy and the extent to which it is prepared to go for the sake of their ‘strategic assets’ for sub-conventional warfare.

Pakistan’s employment of conventional forces with irregulars (lashkars) is as old as Pakistan itself. It happened in 1947-48, 1965 and has been ongoing since the proxy war began in the eighties. In its latest avatar, in the ‘new concept of war fighting’, at the lower end of the spectrum, it hopes to enlarge the scope for sub-conventional operations (terrorists), and at the other end, lower the nuclear threshold by bringing into play (even if it is bluster) tactical nuclear weapons. Pakistan imagines a seamless hybridisation of sub-conventional, conventional and tactical nuclear weapons to limit the time and space for conventional war. Striking military targets in India is provocation enough. Missing the target by design or failure doesn’t lessen the gravity any way. Further, the vulgar display of photographs and videos of the pilot in their custody has only aggravated the situation further.

So, what next? While there must be strong diplomatic, information and economic action, by themselves they would be inadequate given the gravity of the provocation. A military response is therefore axiomatic for India to remain on top of the situation. Issues to be considered are—theatre of response, targets, timing, nature of force, likely casualties and collateral damage. While potential for further escalation is a serious consideration, it would be pertinent to mention that the Balakot strike has to some extent called the bluff on Pakistan’s nuclear sabre-rattling. In dealing with hybrid warfare, we should be guided by long-term objectives and strategy, and every action must contribute towards that. Every opportunity that presents itself must be utilised towards that end.

Presently, Pakistan has shown the first signs of de-escalation with Imran Khan’s announcement of the Indian pilot’s release. But there exists a legitimate window for India until Pakistan demonstrates action against JeM. Till then, India could continue to take well-calibrated military action. The theatre for response should therefore be limited and the scope of targets also perhaps restricted to terrorist infrastructure. This would mark a shift from ‘All-Out War’ to ‘Controlled War’.

(Views expressed are personal)

By Lt Gen Subrata Saha (Retd) Former Deputy Chief of Army Staff and Kashmir Corps Commander, and currently Member, National Security Advisory Board