Coalition experiments haven’t worked in Karnataka. That much has remained constant in a state reeling from political flux over the past months, if not years. When the BJP defeated H.D. Kumaraswamy’s JD(S)-Congress coalition government at Tuesday’s trust vote, it was the third time in 13 years that a ruling alliance had lost the number game. Now, with former chief minister B.S. Yeddyurappa back in the driver’s seat, the BJP gets a second shot at ruling Karnataka.

The denouement itself was laced with irony—it was Kumaraswamy who brought down the Congress-JD(S) coalition, headed by Dharam Singh, in 2006 when he led a faction of his party to a pact with Yeddyurappa. Twenty months later, when Kumaraswamy reneged on that pact to transfer power to the BJP, the second coalition fell. This time around, it was a group of rebels that pulled his 14-month-old government down.

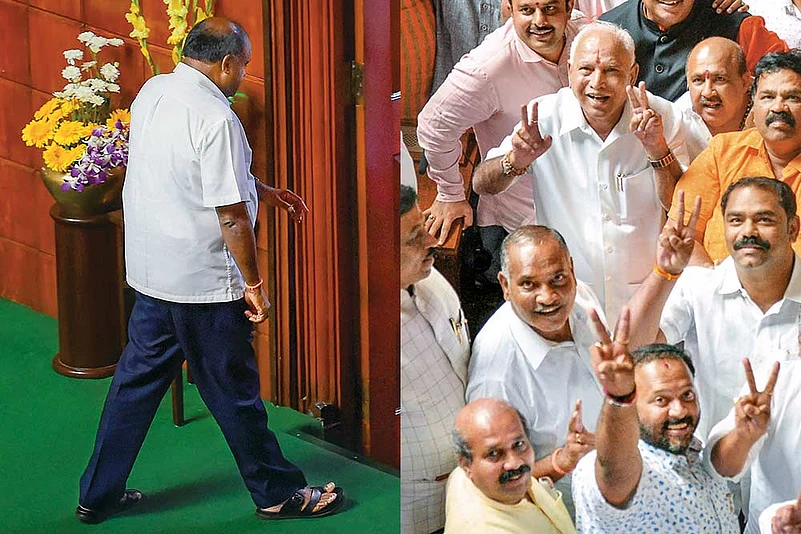

The confidence motion got stretched to four days because the allies hung on to the hope that they could win back some of the 16 rebels. In the final headcount, 20 legislators, including a Bahujan Samaj Party MLA, had stayed away from the vote, giving the BJP, with 105 members, a majority in the truncated assembly.

Through the four days of debate, a confident BJP sat quietly in the opposition benches as the JD(S)-Congress fumed over the defectors—they spoke at length about the crores of rupees that were allegedly offered to the rebels who had resigned, and their trips by special flight to Mumbai where they stayed put. “The business of the House is to discuss business,” wryly noted Speaker K.R. Ramesh Kumar at one point, insisting that every allegation went into the record. “People should know, let everything come out,” he said.

What becomes of the rebels now? There’s a legal aspect, given that they had approached the Supreme Court over their resignations earlier this month. This had triggered discussion in the assembly about party whips and the anti-defection law arising from the court’s interim order that the legislators ought not be compelled to participate in the House proceedings. The Congress and JD(S) have disowned these legislators and pressed for disqualification. “Those who have fallen for Operation Kamala (lotus, the BJP symbol) will never be inducted back. Even if the sky falls,” said Congress leader Siddaramaiah. Bypolls will likely follow, reckon political analysts.

The natural question now is whether the JD(S)-Congress alliance, which was stitched together in 2018, will continue. Kumaraswamy told reporters that the two parties were yet to discuss that and his priority now is to strengthen the JD(S). Congress state president Dinesh Gundu Rao says: “It’s time to build the party again in the state. We are number one in terms of (assembly) vote share. The Opposition got an important role and that’s the role we would want to play now.”

More significantly, the focus shifts to the BJP’s own challenges as a ruling party. “Whether it is going to be a stable arrangement is a bit difficult to guess,” political analyst A. Narayana says. If the numbers are again precariously balanced after bypolls, the political instability is going to continue, he says. The bigger challenge will come from within. The BJP’s first term in office (2008-2013) was wracked by infighting—three chief ministers in five years. If the BJP has to rely on new entrants for strength, it is bound to queer the pitch. Again, a decade ago, the BJP banked on defectors to shore up its wafer-thin majority, resulting in a faction-ridden outfit. “When you have many new entrants from other parties, it’s as good as running a coalition. It also depends on what kind of heartburn it is going to create within the BJP,” says Narayana. Of course, the party scenario has changed since those years, especially with a BJP central leadership firmly in command.

“The BJP never triggered anything. The MLAs who were staying in Mumbai had made their stand that it was of their own volition,” senior BJP leader S. Suresh Kumar tells Outlook. “From Day One, there was distrust (in the coalition) and no attempt was made to correct the trust deficit,” he says. The fractured 2018 verdict made things difficult for any political party but the BJP, he says, is upto the challenge of running the government. “Today, we should learn from those mistakes and we should see that this is a more cohesive unit, and determined,” he says.

By Ajay Sukumaran in Bangalore