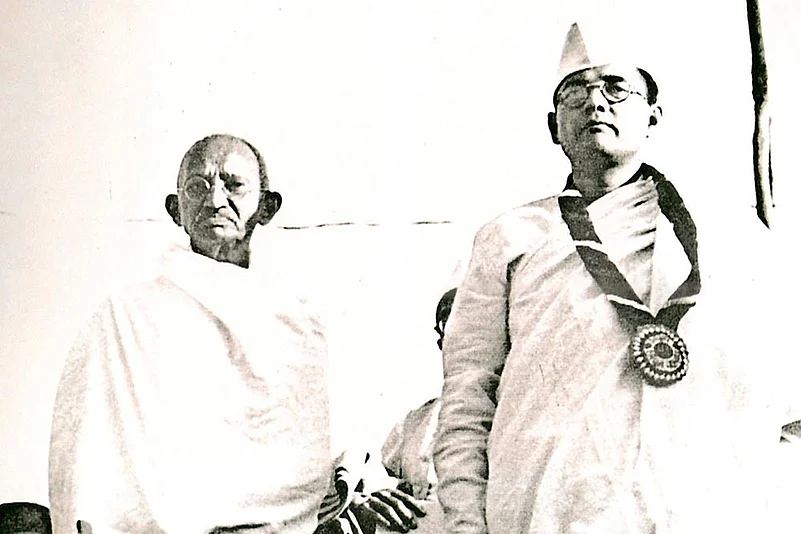

The arrival in February 1938 of a revolutionary leader from Bengal to preside over the 51st session of the Indian National Congress in Gujarat, the home province of the apostle of non-violence, carried powerful symbolic meaning. It represented the meeting of two generations and the merging of two strands of the anti-colonial movement that had often been at odds with each other. The spectacle of Subhas Chandra Bose being taken in a chariot pulled by 51 white bulls to the Congress venue in the rural setting of Haripura connected agrarian and urban India and evoked an idyllic past beckoning a dynamic future. Gandhi and Bose in earnest conversation on the dais at the plenary session of the Congress warmed the hearts of millions of Indians looking forward to a united nationalist stand against the British Raj. The saint’s holiness had to be complemented by the warrior’s sword, as Aurobindo Ghose had argued three decades ago, in the pursuit of justice and righteousness.

The differences of perspective between Bose and Gandhi were not limited to what each considered legitimate methods of anti-colonial struggle. Bose’s dream of a modern industrial future for free India was at variance with Gandhi’s utopia of a Ramrajya, a kingdom of Ram on earth based on self-governing and largely self-sufficient village communities. Yet it was quite possible that their commonalities in the anti-imperialist effort and a sense of mutual respect and affection would enable them to work together in relative accord.

India’s two men of destiny had first met nearly 17 years ago. After resigning from the Indian Civil Service, Subhas Chandra Bose had set sail for India with an unwavering sense of mission to serve his country’s cause. He landed in Bombay on July 16, 1921 and rushed to see Gandhi the same afternoon. Seven years later, at the open session of the Calcutta Congress, Subhas sponsored an amendment demanding “complete independence” instead of “dominion status” in opposition to Mahatma Gandhi. He simply did not believe that there was any “reasonable chance” of the British granting “dominion status” within twelve months, as was demanded in the main resolution. Gandhi promised that if the year 1929 did not bring dominion home rule, he would himself become an “independence-wallah”.

“I shall probably be elected the president of the Indian National Congress early next year,” Subhas wrote in a private letter on September 9, 1937. Gandhi had clearly broached the subject with him by this time. In late October 1937, the Bose brothers, Sarat and Subhas, were the cynosure of the anti-colonial movement as the top leadership of the Indian National Congress gathered in Calcutta. The entire top floor of Sarat Bose’s home at 1, Woodburn Park, was given over to Mahatma Gandhi and his entourage.

As Congress president, Bose tried hard to work in cooperation with Gandhi. Congress participation in coalition governments in the Muslim-majority provinces, in Bose’s opinion, would strengthen the party in speaking with the British. He spelled out to Gandhi what he saw as the need of the hour in clear terms: “While endeavouring to bring about a coalition ministry in the remaining three provinces, we should lose no time in announcing our decision on the various Hindu-Muslim problems that would have come up for discussion if negotiations had taken place between the Congress and the Muslim League. Simultaneously, we should hold an enquiry into the grievances of the Muslims against the Congress governments. These two steps will help to satisfy reasonable Muslims that we are anxious to understand their complaints and to remedy them as far as humanly possible.”

A proposal to conduct an enquiry into the conduct of Congress ministries in the Hindu-majority provinces was a red rag to the right wing of the party comfortably enjoying the fruits of office. Bose’s approach in addressing the intertwined challenges to the construction of an all-India nationalism presented by affiliations of religious community and linguistic region was significantly different and substantially more generous than that of most others among the Congress leadership.

The democratic verdict of the delegates from the provinces after an unprecedented electoral contest was delivered on January 29, 1939. The final tally showed that Subhas Chandra Bose had emerged victorious by 1,580 votes to the 1,375 votes Gandhi’s choice, Pattabhi Sitaramayya, got. As was to be expected, Bengal had voted decisively for Bose, while Gujarat and Andhra had gone Sitaramayya’s way. Among the major provinces, Bose had carried the United Provinces, Punjab and Assam in the north and Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu in the south. For the first time in two decades, Gandhi’s authority had been successfully challenged within the Indian National Congress. “It will always be my aim and object,” Subhas promised, “to try and win his confidence for the simple reason that it will be a tragic thing for me if I succeed in winning the confidence of other people but fail to win the confidence of India’s greatest man.”

The right wing of the Congress struck a calculated political blow at Tripuri in their campaign to avenge their defeat in the presidential election. They brought a resolution moved by Govind Ballabh Pant that “the Congress executive should command [Gandhiji’s] implicit confidence and requests the president to nominate the Working Committee in accordance with the wishes of Gandhiji”. Once it was clear that an impasse had been reached, Bose submitted his resignation as Congress president “in an entirely helpful spirit” at the meeting of the All India Congress Committee in Calcutta on April 29, 1939. Bose’s conduct won the approbation of no less a figure than Rabindranath Tagore, for the dignity Subhas had displayed.

During the war crisis that erupted in September 1939, the rest of the Congress leadership behaved like His Majesty’s Opposition; having shed all inhibitions of colonial subjecthood, Bose alone stood forth as His Majesty’s Opponent. While Subhas was kept under close police watch in his home at 38/2 Elgin Road following his hunger-strike, not even the letters he exchanged with Mahatma Gandhi could evade the prying eyes of the colonial state. On December 23, 1940, Bose wrote to Gandhi offering his unconditional support to any movement the Mahatma might lead in the cause of India’s independence. “You are irrepressible, whether ill or well,” Bapu wrote to his rebellious son on December 29, 1940. “Do get well before going in for fireworks.” On January 3, 1941, the government censors opened and read this letter. Little did they know that the rebel had already completed preparations for his fireworks and was simply waiting for the right moment to light the fuse. On the night of January 16-17, 1941, Subhas escaped from Calcutta driven in a German-made Wanderer car by his young nephew Sisir.

Netaji reviewing the Rani of Jhansi regiment in Singapore.

By 1942, Mahatma Gandhi and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose had a shared perspective on the war. The historical significance of Netaji’s submarine voyage from Europe to Asia that began on February 9, 1943 is underscored by the British response to another crucial development in India on the same day. This was the commencement of Mahatma Gandhi’s fast that was to keep Indians on tenterhooks for three weeks. The British cabinet had decided that if Gandhi fasted he would be allowed to die. Flush with the victories at El Alamein and Stalingrad, Churchill was of the clear opinion that “this our hour of triumph everywhere in the world was not the time to crawl before a miserable old man who had always been our enemy”. In the event of Gandhi’s death, Linlithgow expected “six months’ unpleasantness steadily declining in volume; little or nothing at the end of it”. Linlithgow thanked Churchill for refusing to yield to “the world’s most successful humbug” who was engaged in a “wicked system of blackmail and terror”. At a time when the Quit India movement was nearly crushed and the Mahatma was being treated with scant respect, Netaji alone was showing grit and a determination to fight the colonial masters.

The first division of Netaji’s Azad Hind Fauj in Southeast Asia was divided into three brigades named after Gandhi, Nehru and Azad in a conscious effort to make common cause with the struggle at home. Just as the three battalions of the INA’s Gandhi brigade commanded by Inayat Kiani started arriving in Burma from Malaya, Netaji received news that Kasturba, the Mahatma’s wife, had died in Poona while in British custody. In a broadcast from Rangoon he paid a moving tribute to the “great lady who was a mother to the Indian people”.

Once the Mahatma was released from prison in India, Netaji made a lengthy radio address to him on July 6, 1944. He lauded the Mahatma once more for bravely sponsoring the ‘Quit India’ resolution. The mission of the provisional government he had set up would be over once India became free. S.A. Ayer observed Netaji intently in the studio as he prepared to deliver the last line of his address. “Father of our Nation!” he began. He voice turned hoarse, then quivered, and a solemn look came over his face. His throat cleared and the words came out clear and strong: “In this holy war for India’s liberation,” and then a pause, a lowering of the pitch and in a tone of supplication, “we ask for your blessings and good wishes.”

In December 1945, the Mahatma paid homage to his rebellious son Subhas in the bedroom of the Elgin Road home from where he had made his great escape in 1941. “Netaji’s name”, Gandhi wrote in the Harijan on February 12, 1946, “is one to conjure with. His patriotism is second to none. His bravery shines through all his actions. He aimed high but failed. But who has not failed? Ours is to aim high and to aim well…. The lesson that Netaji and his army brings to us is one of self-sacrifice, unity--irrespective of class and community—and discipline.”

Netaji, Gandhi told military men who came to visit him in Uruli Kanchan in March 1946, had “rendered a signal service to India by giving the Indian soldier a new vision and a new ideal”. The Mahatma initially harboured a hope that Netaji would return to join him in the work for unity. On March 30, 1946, Gandhi explained in the Harijan his earlier “feeling that Netaji could not leave us until his dreams of swaraj had been fulfilled”. “To lend strength to this feeling,” he added, “was the knowledge of Netaji’s great ability to hoodwink his enemies and even the world for the sake of his cherished goal.” His “instinct” had suggested to him “Netaji was alive”. He now could no longer rely on “such unsupported feeling” as there was “strong evidence to counteract the feeling”. “In the face of these proofs,” the Mahatma wrote, “I appeal to everyone to forget what I have said and, believing in the evidence before them, to reconcile themselves to the fact that Netaji has left us. All man’s ingenuity is as nothing before the might of the one God. He alone is Truth and nothing else stands”.

At Dalta in Noakhali on January 23, 1947, the Chowdhuris of the village gifted Gandhi the plot of land on which his prayer meeting was held. He was glad that on the auspicious birthday of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose he had received this gift. He reminded his audience that Netaji was “an Indian first and last” and that “he fired all under him with the same zeal, so that they forgot in his presence all distinctions and acted as one man”. Subhas had “in his life verified the saying of Tulsidas that all becomes right for the brave”.

The final week of the Mahatma’s life was rich with symbolism redolent of India’s unity. On January 23, 1948, Gandhi was “very glad” to take note of Subhas’s birthday, even though he “generally did not remember such dates” and “the deceased patriot believed in violence”, while he was wedded to non-violence. Subhas, according to the Mahatma, “knew no provincialism nor communal differences” and “had in his brave army men and women drawn from all over India without distinction and evoked affection and loyalty, which very few have been able to evoke”.

A lawyer friend had requested Gandhi for a good definition of Hinduism. He did not have any, but suggested that “Hinduism regarded all religions as worthy of all respect”. Subhas Bose, according to him, was “such a Hindu” and so, “in memory of that great patriot”, he called upon his countrymen to “cleanse their hearts of all communal bitterness”.

What the Mahatma and Netaji shared in their vision of equality and unity among all religious communities of India far outweighed their temporary differences in 1939.

Sugata Bose Gardiner Professor of Oceanic History and Affairs, Harvard University, and great-nephew of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose