“Another year has rolled by,” Subhas Chandra Bose wrote on January 8, 1913, to his elder brother Sarat, “and we find ourselves responsible to God for the progress or otherwise that we have made during the last twelve months.” Subhas, not yet 16, saw darkness, despair and decline engulfing India, but “the angel of hope” had appeared in the form of the message of “the saintly Vivekananda”. That seemed to provide some solid ground for Tennysonian optimism. “A brighter future is India’s destiny,” Subhas told his brother. “The day may be far off—but it must come.”

Has that longed-for day finally dawned in India? The usual stocktaking that takes place as we bid adieu to the year gone by and welcome the new is rendered especially difficult for 2009. The year has witnessed the severest global economic crisis in eight decades. The turmoil is not over and the trajectory of recovery is uncertain at best. Our country has weathered the storm unleashed by the financial meltdown since September 2008 reasonably well. While the US struggles with double-digit unemployment, the UK declares a virtual financial emergency and much of the world is mired in recession, India’s economic institutions are in a healthy state and its growth rate chugs along at a decent pace. Before granting our government some kudos for sound macroeconomic management, however, one has to note its abysmal failure in reining in runaway inflation in food prices.

This is a worrying trend that has not been a feature of generalised liquidity crises in the past. Food prices have not, as they generally did during the great depression and other downturns, followed close on the heels of the irremediable downward slide of commercial crop prices. Today food prices are continuing to run high in many economies, including India, where it is touching 20 per cent. This at a time when other commodity prices tanked, prompting India’s economist prime minister to assuage worries in mid-year with a statement that he does not see any dangers of a deflationary spiral. How best to ensure entitlements to food security of the world’s poor and obscure ought to be one of the top priorities for 2010. An erratic and indifferent monsoon is not an acceptable excuse for India’s inaction on this front. Policy instruments available to tackle this problem have just not been deployed, revealing perhaps of our government’s priorities and predilections.

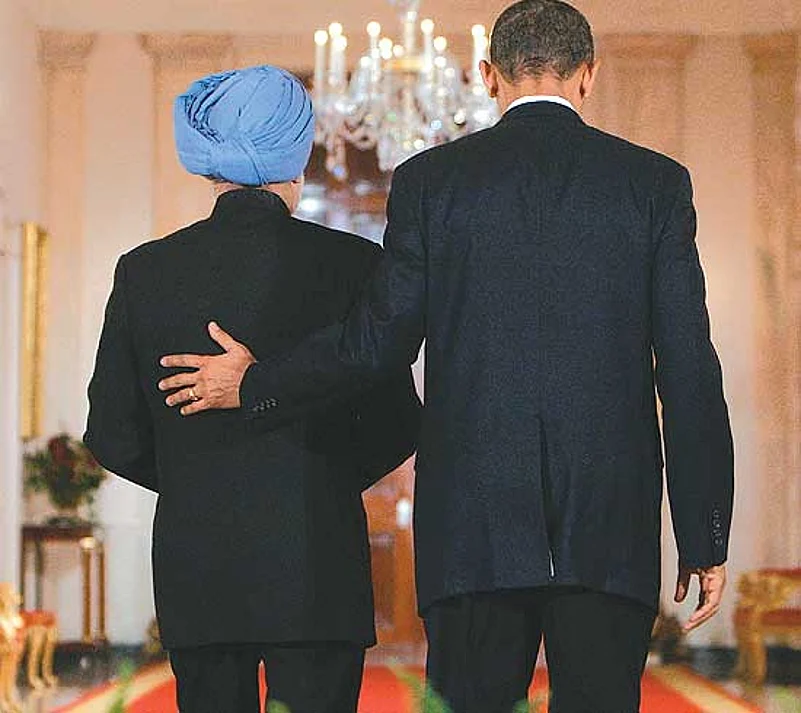

For those who hailed India’s new strategic partnership with the US in 2008, the attitude of the Barack Obama administration has felt like something of a letdown. The fanfare surrounding the first state dinner hosted for our prime minister in November has seemed poor recompense for the far greater importance that the US attached to China. Disappointment with Obama’s or the Democrats’ preferences is, however, to miss the point. The economies of the US and China are inextricably tied in a deep symbiotic relationship. To put it bluntly, the US is in debt to China, which it is not to India. Since American economic recovery is likely to take three or four years to take hold, one should expect the US administration to treat the pre-eminent Asian giant with due deference in the short term. Converging economic and strategic interests will shape the relationship between India and the US in the medium and long term. We will likely witness shifting alignments in bilateral ties and multilateral cooperation in 2010 depending on the particular issue at hand, ranging from trade to climate change.

Regional Tensions: It is a truism to say that India lives in a troubled neighbourhood. Our ambitions to play a prime role on the global stage have been often hobbled by an inability to rise above the quagmire of conflicts in the South Asian region. The dark shadow of the horrific Mumbai attacks of November 2008 hung over the country throughout 2009. Even though a year has fortunately passed without the repetition of a similar terrorist outrage, the situation across the northwestern borders in Pakistan and Afghanistan has, if anything, deteriorated dramatically. Pakistan’s cities have witnessed a spate of suicide bombings, taking a heavy toll of civilian life.

As 2010 dawns, there needs to be a reasoned debate in the country as to whether further fragmentation or relative stability in Pakistan would serve India’s long-term security interests. What will be the implications of chaos and anarchy across the northwestern borders for the prospects of growth and prosperity within them? Is indefinite diplomatic non-engagement the best way forward for India? Surely, the most effective way of dealing with terrorism is not to let the terrorists call the shots or set the agenda in terms of subcontinental relations. Much will depend in this area on the ability of India’s leadership to carry public opinion in a transparent exercise of public diplomacy.

The regional conundrum has, of course, a key global dimension. The American military surge in Afghan-istan has been declared by Obama to be inherently time-bound in nature. His awkward speech at West Point in November, pandering to many contradictory constituencies, called for the beginning of a withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan in 18 months. If he is to keep his word, a deal with reconcilable Taliban cannot be ruled out. India has to prepare for an eventuality where the world’s policeman abdicates its policing role in the region before realising its military objectives.

Domestic Triumphs and Trials: The victory of the Congress-led alliance in the general elections of May 2009 was the result of a remarkable political intuition on the part of India’s electorate, which did not want India’s central government to be held hostage to a plethora of particularist interests based on caste, religion or region. The prospect of a stable government for five years felt reassuring and the promise of inclusive growth sounded alluring in the summer of 2009. Yet the gap between prospectus and performance may well herald a winter of discontent.

For all the rhetoric of inclusion, far too many of our less fortunate citizens face the cold winds of exclusion from India’s much-vaunted story of rapid growth. Perhaps the most marginalised are the tribal populations who inhabit a vast swathe in the middle of the country. The problem cannot be addressed by merely wielding the rod of order. It is vitally important to acknowledge the intrinsic connection between socio-economic deprivation and political belligerence. That done, enhancing capabilities in relation to health, nutrition and education need to be taken up in earnest so that a grim economic crisis can become a turning point for expanding social opportunity that has so long been denied.

As the year drew to a close, the eruptions in Andhra and Telangana served as a stern reminder of the Indian union’s longstanding ineptitude in negotiating the challenge of regional difference. As early as the 1920s, the Congress had promised federalism based on the linguistic reorganisation of state boundaries. Yet no sooner had independence been won that the Congress under Nehru tried to block this process. On October 20, 1952, Potti Sriramalu—a Gandhian—began a fast unto death unless the Centre agreed to the principle of creating a separate state of Andhra. Nehru remained unmoved and on December 15, 1952, Sriramalu died of starvation. This was ironically the same day that Nehru presented the preamble of his First Five Year Plan for India’s development to Parliament, describing it as the “first attempt to create national awareness of the unity of the country”. News of the Telugu leader’s death sparked off riots in all eleven Telugu-speaking districts of Madras. On December 18, 1952, the central cabinet decided that the state of Andhra would be created.

It took a much shorter and less tragic fast in December 2009 for the central government to yield to the principle of creating a Telangana state. Yet what is common to the two stories is the perception of central perfidy in dealing with regional aspirations. State plans and markets can at best achieve integration. It requires a generous and imaginative articulation of the idea of India to craft genuine unity based on a respect for difference that creates a sense of belonging among the country’s diverse regional peoples. On the success of that articulation depends the realisation of the brighter future that was seen nearly a hundred years ago as India’s destiny.

(The writer is Gardiner Professor of History and director at the South Asia Initiative of Harvard University.)