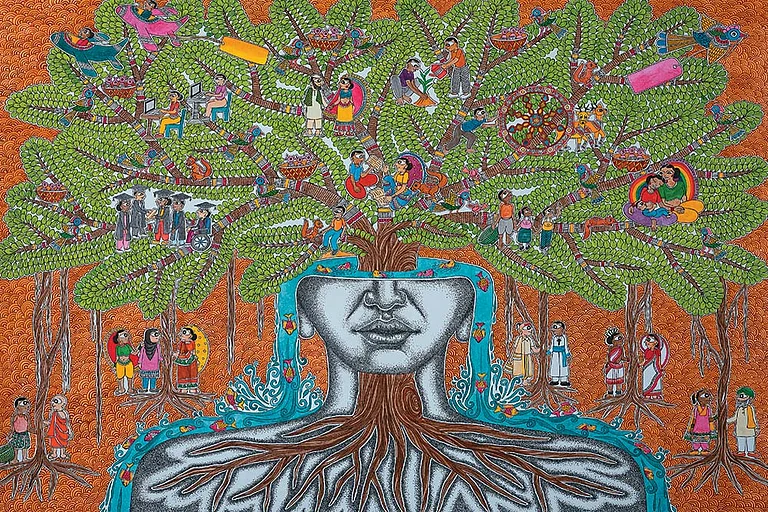

Education, as a matter of right, appears a distant dream for the nearly hundred youngsters in Dhapani village in the remote Santhal Pargana division in North-East Jharkhand. Until 2018, the Paharia children studied in Dapani village, home to about 80 households. Once influential, the Paharia tribe is now dwindling in numbers and losing socio-political clout compared to larger tribes like the Santhals. In 2018, the local school was relocated to another village three kilometres away. Despite a 2022 petition prompting the district administration to promise reopening the Dhapani school, it remains shut. With no proper road between the villages, Paharia students continue to struggle without basic education.

Recently, in nearby Pergodda village, a 13-year-old Paharia girl was married off, only to be sold by her husband to Panipat when she turned 16. According to Shikha Paharia, a local activist, poverty, limited access, unemployment and illiteracy have driven many Paharia families to send their young children away as bonded labourers, just to survive. “There is a feeling of abandonment,” says Paharia while articulating the need for a focussed approach on part of the administration to help Paharias find their feet. Paharias are one of the eight primitive tribes—among 32 notified tribal communities in Jharkhand—who call the Santhal mountains their home, but now face a fight for their very existence.

Devi Singh Paharia, who works for his community through the Adim Janjati Adhikar Paharia Manch, said that they are disappointed with both, the state and the central governments. “We do not get the benefit of any scheme. Our children and women suffer from the worst form of malnutrition. Our population has been declining. We have neither an MLA nor an MP. Our calls for constituting an Adim Janjati Commission [Primitive Tribe Commission] go unheeded,” he said.

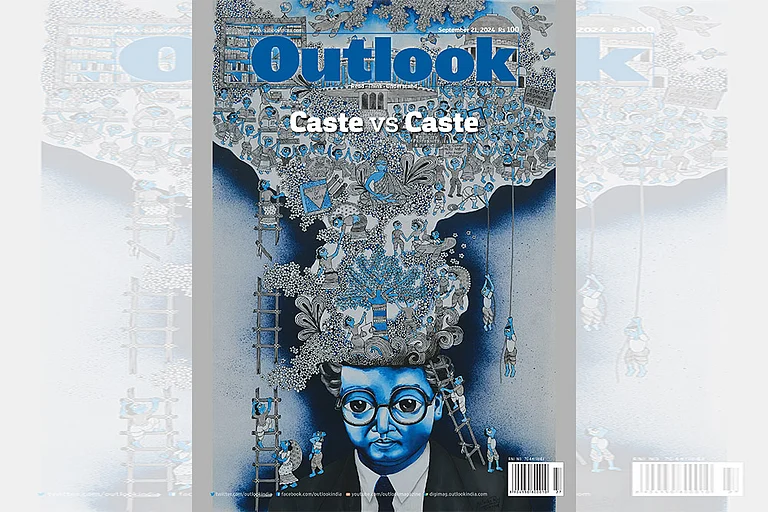

The Paharia community’s hopes were lifted by the recent Supreme Court ruling in favour of subclassifications within the Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) reservations. However, in the face of caste politics and the silence of political parties vis-à-vis their plight, this new-found optimism now feels like little more than self-consolation.

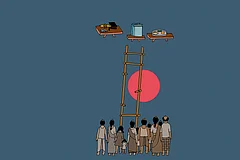

According to Paharia, political representation is key to address his community’s concerns. He believes applying the creamy layer principle to ST reservations, like in the OBC category, could slightly improve his community’s situation and maybe even throw up a Paharia representative in the state assembly.

In August this year, the Supreme Court approved sub-quotas within SC and ST reservations to benefit the most backward sections, a move that could positively impact small tribal subgroups like the Paharias. Despite this ruling, political parties distanced themselves, and the government stated that reservations would remain unchanged under Articles 341 (SC) and 342 (ST) of the Constitution.

The 2011 census showed tribals make up 8.5 per cent of India’s population. According to experts, primitive tribes, the most marginalised, have a negligible population and barely stand out at the state level, which, in turn, discourages political parties from advocating for their interests.

Jharkhand’s population of 3.29 crore includes 86.35 lakh tribals, with only 2.92 lakh belonging to particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs). Nearly half of this small group are Paharias, fighting for their very existence. Census data from 2001 and 2011 appears to suggest that despite a rise in the overall tribal population in Santhal Pargana, the Paharias are edging towards extinction.

The Paharias are split into three sub-groups: Mal Paharia, Kumarbhag Paharia (General Paharia), and Sauria Paharia. The Kumarbhag Paharias are nearly extinct, with their population dropping from 2,649 to 641 between 2001 and 2011. The Mal Paharia population fared better, increasing by 31,410 to 1,32,529. Overall, the Paharia population saw a slight rise from 1.47 lakh to 1.48 lakh, while the population of Santhals, a major tribe, grew significantly from 11.60 lakh to 17.46 lakh.

In recent years, many Paharias have migrated to urban centres due to mining impacts, contributing to their population decline. Similarly, the Asur, Birhor, Virjia, Korwa, and Sabar tribes live in poor conditions and have long demanded political representation. In 2014, Vimal Asur ran for office in Bishunpur, Gumla, as a candidate for the Jharkhand Vikas Morcha (now merged with BJP) but garnered only a few thousand votes.

Apart from Asur, Simon Malto, who ran as a BJP candidate from Santhal in 2019, was the only other primitive tribal candidate to contest an assembly election. Neither succeeded in winning. In the 24 years since Jharkhand’s formation, no primitive tribal representative has become an MLA. This trend also persisted before statehood, during unified Bihar, where no primitive tribal MLA or MP was elected, and political parties did not nominate them to the Legislative Council or Rajya Sabha.

Senior journalist Sanjay Krishna argues that the condition of primitive tribes in Jharkhand is worse than in other states and that reservation is crucial to integrating them into the mainstream like other tribals. “Tana Bhagat and the Paharias played a significant role in the fight against the British. Documents show Tilka Manjhi, a Paharia, was the first tribal to lead a revolt against the colonisers around 1765. Just as seats were once reserved for Anglo-Indians in the Jharkhand Assembly, similar reservations are needed to uplift the primitive tribes,” he says.

Krishna suggests increasing the number of Assembly seats from 81 to 90, with five to eight seats reserved for primitive tribes. He also believes there is a greater need for reservations within the SC category than the ST category. In its brief history, Jharkhand has had six tribal and one non-tribal chief minister. Four of the tribal chief ministers were from the Santhal tribe, while one each was from the Munda and Ho tribes. Since independence, most MLAs, MPs, and ministers in Jharkhand have come from the Santhal, Munda, Oraon and Ho tribes.

On August 21, a bandh was called in protest against the Supreme Court’s judgement, with support from all political parties in Jharkhand. No party opposed the protest. Interestingly, while the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s (RSS) Janajati Suraksha Manch has called for the abolition of reservations for tribals who are Christians or Muslims, it opposes the Supreme Court’s “creamy layer” ruling for tribals who are educationally, economically and politically empowered. Experts note that most members of the Janajati Suraksha Manch in Jharkhand are from the Oraon and Munda castes.

Despite promises of substantial funding and support, the struggle of Jharkhand’s primitive tribes underscores a glaring disparity.

In November last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi pledged Rs 24,104 crore to uplift these communities. Yet, as these tribes continue to face severe socio-economic challenges, one question persists: after 75 years of independence, why have they remained so far behind their counterparts?

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

According to Shikha Paharia, the hardships faced by the Paharias, particularly women, are acute. “Due to child marriage, the Paharia women are suffering from malnutrition and anaemia. You will hardly find one or two matriculates and graduates or intermediates in the village. In Santhal Pargana, the minor girls (10-16 years) of our community are being trafficked the most. If the government wants to develop us, it should make a provision for special reservations for us or listen to the Supreme Court. Otherwise, our condition will worsen by the day.”

(Translated by Kaushika Draavid)

(This appeared in the print as 'Fading Folks')