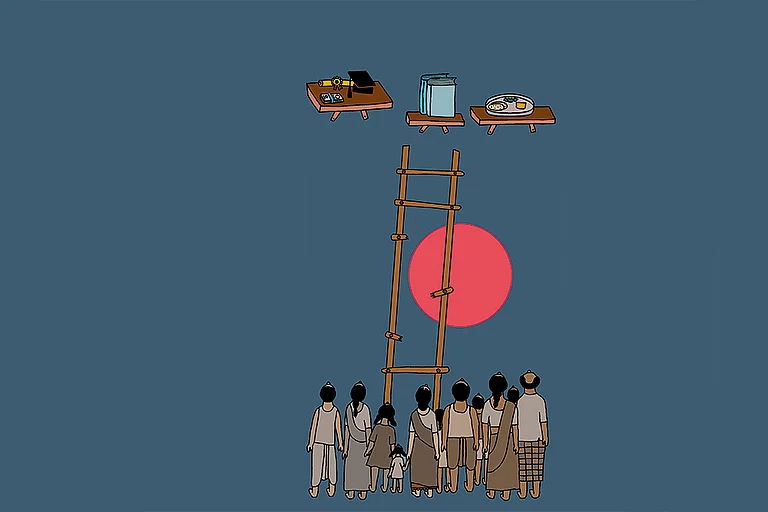

The Supreme Court of India, in its historic judgement on August 1, 2024, permitting sub-classification within the Scheduled Caste category, referred to an article authored by Ravichandran Bathran that was published in the Economic and Political Weekly in November 2016. In Paragraph 141, the court states, “In Tamil Nadu, when an Arunthathiyar man and a Paraiyar woman—both the castes find a place in the Scheduled Castes (SC) list—eloped, the woman’s family allegedly raped the women of the man’s family in retaliation.” The seven-judge bench relied on Bathran’s article to justify the need for the sub-classification within the SC categories so as to argue that discrimination among and within the Dalit communities does exist in India.

Bathran, the man ‘who has become a footnote’ in the historic Supreme Court judgement, himself comes from the most downtrodden Chakliar/Arunthathiyar community in Tamil Nadu. Historically, the Chakliar/Arunthathiyar community was engaged in manual scavenging, a caste-based labour imposed on them. Bathran, a post-doctoral fellow, worked at the University of Southampton, South Africa. Despite being a scholar, Bathran runs a company for cleaning toilets. ‘Going back’ to manual scavenging was never a choice, says Bathran. “I wanted to do research, but they shut the door on my face. I applied to around 10 universities to do research on manual scavenging. But none of the universities responded,” he says.

He converted to Islam in 2022 and changed his name to Raees Mohammed. “As Ambedkar embraced Buddhism, I embraced Islam,” says Mohammad. He runs the Kotagiri Septic Tank Cleaning Services Private Ltd, a company offering scavenging services in Nilagiri district.

Mohammed argues that the hierarchical layers of discrimination within the SC categories often go unnoticed because even some Dalit activists do not want to highlight them.

Pioneering Bahujan Politics

Historically, Tamil Nadu is the state that pioneered the effective implementation of reservation as a tool to address social justice. Long before the rise of Bahujan politics in the north, the public sphere of Tamil Nadu was shaped by affirmative action aimed at social justice. The social justice movement in Tamil Nadu played a pivotal role in advancing reservation as a means for the upliftment of backward communities.

Tamil Nadu is one of the states that first implemented the sub-classification within the SC category. In 2009, the state government introduced a three per cent reservation for the Arunthathiyar community—one of the most backward groups among the Dalits—within the 18 per cent reservation allocated to the SC category in general. This amendment in the reservation rules followed the findings of the Justice M S Janarthanam Committee, which noted that the representation of the Arunthathiyar community was considerably low in the SC category, both in government services as well as in educational institutions as compared to other caste categories.

The Dalit activists and scholars in Tamil Nadu do not agree with the general perception that sub-classification would lead to the weakening Dalit unity. “There is no evidence to arrive at such a conclusion,” says Punitha Pandian, the vice chairman of the Tamil Nadu State Commission for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Pandian, who is also the founder editor of Dalit Murasu, argues that there is a disproportionate gap between different SC communities. The Tamil Nadu experience indicates that the perceived Dalit unity does not even exist otherwise. In the paper “The Many Omissions of a Concept: Discrimination Amongst Scheduled Castes,” quoted by the seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court, Bathran argues that SCs are not a homogeneous community and that discrimination within Dalits does exist.

Roots of Reservation

The reservation policy of the state has its roots in the anti-Brahmin movement led by the Justice Party in the early 1900s. The non-Brahmin manifesto was published in 1916, demanding adequate representation for non-Brahmin communities in employment and education. The manifesto pointed out that 94 per cent of employment in the government sector was held by Brahmins. The Justice Party, which won the Madras Presidency Legislative Council election in 1920, took the pioneering step for community-based reservation by issuing the Communal GO (Government Order) in 1921. It provided 44 per cent reservation for non-Brahmins, including Muslims, Christians, and Adi Dravidas and 16 per cent for Brahmins.

Based on the recommendations of the A M Sattanathan Committee, the DMK government in 1970 increased reservation for the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) from 25 per cent to 31 per cent, and reservation for SCs/STs from 16 per cent to 18, enhancing the state’s total reservation to 49 per cent.

Reservation: A Political Tool

In later years, reservation for the backward communities became a tool for political gains. In 1979, the AIADMK government, headed by M G Ramachandran, introduced the ‘creamy layer’ concept in the backward class (BC) reservation, which ignited widespread protests in the state. In the wake of these protests and the defeat faced by AIADMK in the 1980 Lok Sabha polls, MGR withdrew the creamy layer order and increased OBC reservation to 50 per cent, raising the total reservation to 68 per cent.

The Second Backward Class Commission, which came into existence in 1982 and submitted its report in 1985, sparked another political controversy in Tamil Nadu. The Commission, headed by J A Ambashankar, recommended reducing backward class reservation to 32 per cent and to delete 34 communities from the OBC list.

Tamil Nadu witnessed fierce protests organised by the Vanniyar Sangam, the organisation of the Vanniyar community and the most prominent group among the BC castes. The protests turned violent, leading to police firing and clashes with Dalits. The DMK government, which came into power in 1989, split the OBC quota and created a new category as Most Backward Classes (MBCs). Vanniyars were included in MBCs along with 107 other communities, and were given 20 per cent within the 50 per cent reservation for OBCs in general. An additional one per cent reservation for the Scheduled Tribes (STs) was also introduced, raising the total reservation to 69 per cent.

Backtracking on the reservation that had already been granted is out of question, considering the volatile political situation in Tamil Nadu. The AIADMK government headed by J Jayalalithaa enacted the Tamil Nadu Backward Classes, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Reservation of Seats in Educational Institutions and of Appointments or Posts in the Services under the State) Act in 1994. This Act was included in the Ninth Schedule of the Constitution to evade judicial review. Though other states were struggling with the question of inclusion while keeping the cap on reservation at 50 per cent, in adherence to the Supreme Court ruling, Tamil Nadu took constitutional measures to protect its reservation policy.

The Dalit Question

However, the criticism against the Dravidian model of reservation brings the Dalit question to center stage. While the BC castes gained considerable social mobility through reservation, the SC communities remain far behind. Critics interpret Tamil Nadu’s battle for social justice was more anti-Brahmin than anti-caste. The reservation policy has moved far away from its initial objective of social justice and has become a political tool for electoral gains. This argument was further validated by the DMK government’s policy of providing a 10.5 per cent quota for the Vanniyar community within the prescribed 20 per cent quota for the MBCs. The Tamil Nadu Special Reservation Act (2021), which granted Vanniyars a special 10.5 per cent quota within the quota, was struck down by the Madras High Court on November 1, 2021, citing lack of evidence, and this judgement was upheld by the Supreme Court on March 31, 2022.

“Even the celebrated Communal GO that established reservation in 1921 was not pro-Dalit,” says Shalin Maria Lawrence, author and activist. “In the Communal GO, 16 per cent reservation was given to Brahmins, who comprised only three per cent of the population. On the other hand, Dalits were given only eight per cent reservation, despite the fact that their population is around 19-21 per cent,” she says.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

On August 8, Bathran aka Raees Mohammed wrote on Facebook: “At last whatever efforts I put in my life with sacrifices, the mainstream has recognised in their ‘footnote’. Life has become a ‘footnote’.

(This appeared in the print as 'The 69% Exception')